Have you heard of that new restaurant in town?

If you've been ordering food online since the start of the pandemic, you may have noticed a bunch of new restaurants in your area that suddenly appeared. Let's look at the economics of ghost kitchens.

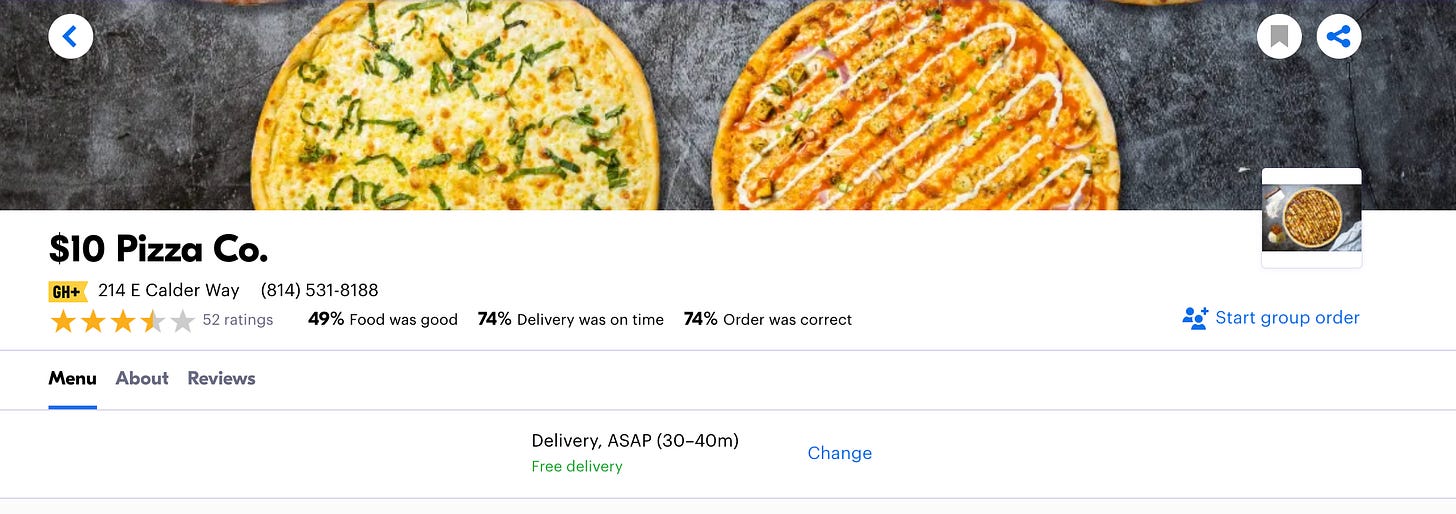

I was looking for lunch one day, so I logged onto Grubhub to get some ideas. All of a sudden, a recommendation pops up for a pizza place that I’ve never heard of before: $10 Pizza Company. State College is small enough that new restaurants, especially downtown locations, are covered in the student newspapers. This one didn’t seem familiar:

I don’t love food reviews on sites like this because sometimes the poor ratings are related to the delivery side of things and not based on the quality of the food. I decided to head over to Yelp! and see what people were posting there. Oddly enough, there was no listing for the $10 Pizza Co. in State College, PA:

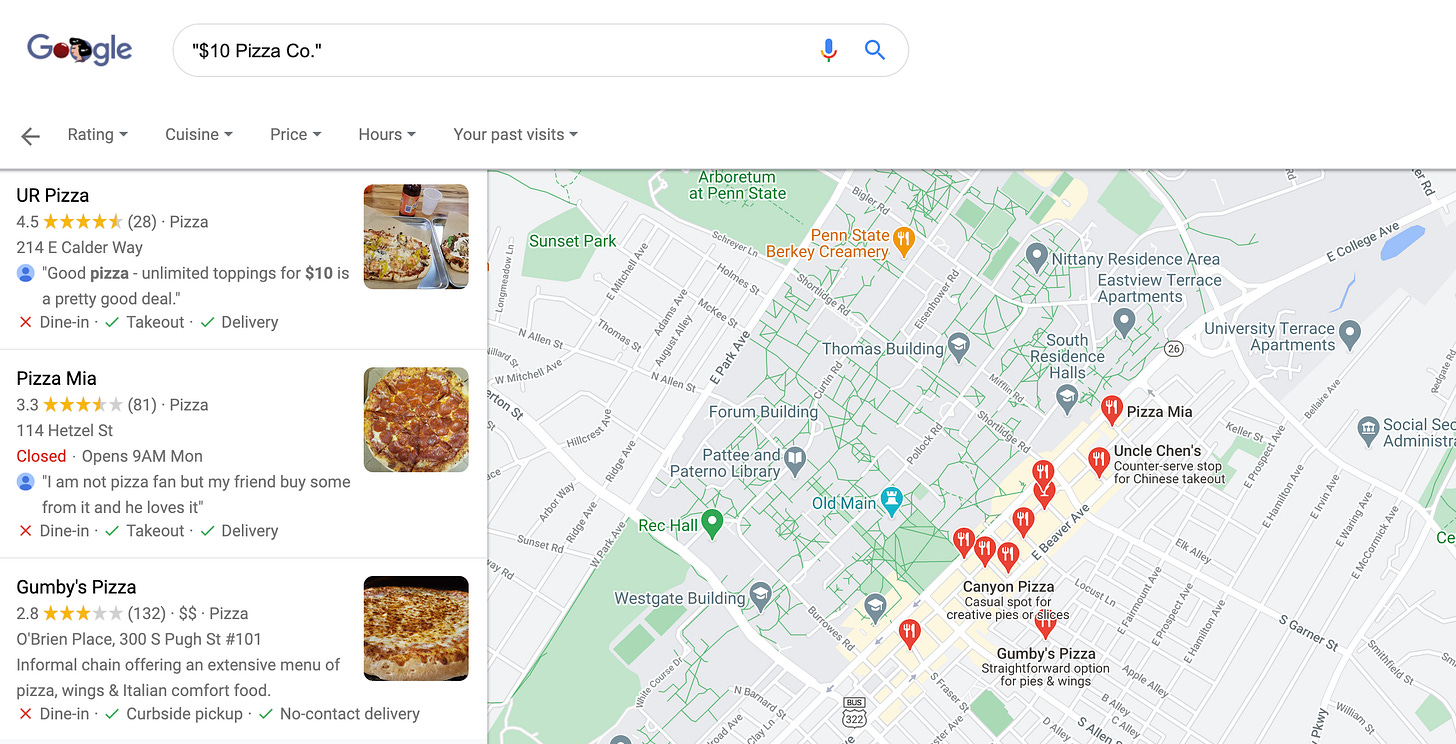

While strange, it’s possible a brand new restaurant just hadn’t gotten a Yelp! listing yet. By this point, I’d already forgot that people had been rating the place on Grubhub for a few months. No worries, Google reviews tend to pop up very quickly for a lot of new restaurants. Let’s see what the fine people who leave Google reviews had to say:

Even Google can’t seem to locate this $10 Pizza Co., but plenty of other pizza places popped up downtown. If you noticed the address on that original Grubhub listing, it’s actually the same address as UR Pizza. It’s either one company posing as multiple companies or it’s an example of Grubhub creating a fake company to “grow” their business. Both of these moves have been popping up a lot because of the pandemic. This famously happened in Philadelphia when a Grubhub user noticed that their “local” pizza from Pasqually’s was actually from Chuck E. Cheese:

Grubhub is also (in)famous for creating entirely fake websites that look like restaurants and then taking your order and placing it at a real restaurant with the same dishes. This behavior isn’t just exclusive to Grubhub. In an interview with Eater, Postmates’ Director of Business Development didn’t see the issue with creating fake listings and instead changed the focus to their role in the transaction:

We’re a pick-up service representing the customer; we’re not a delivery service representing the restaurant. There’s a big difference.

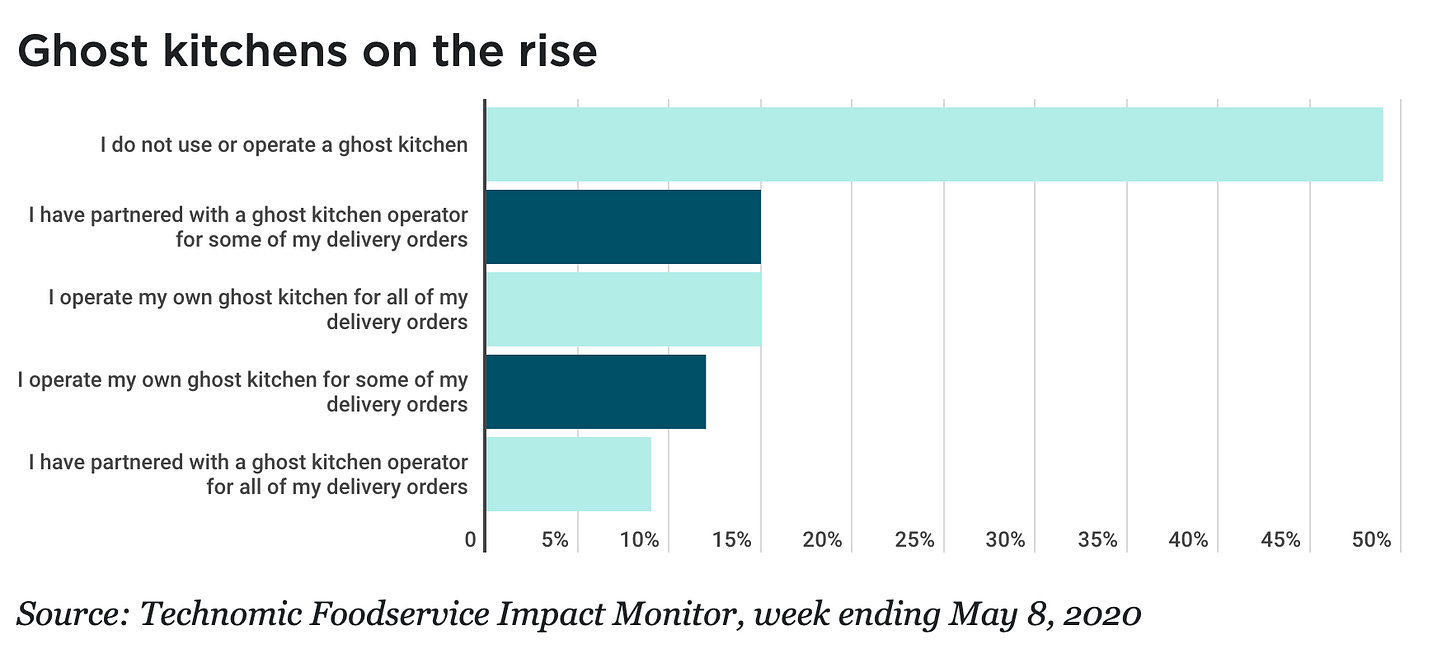

The second wave of restaurant “innovation” has come in the form of ghost kitchens. Occasionally ghost kitchens can become mystery restaurant listings, but broadly speaking they are restaurants that only offer take-out and delivery. Some big-name chains have gotten into the trend, including Chipotle and Jersey Mike’s. Based on research by Technomic and the National Restaurant Association, 51% of restaurant operators reported using a ghost kitchen last year:

Whether it’s partnering with a ghost kitchen for delivery orders or creating a delivery-only “restaurant” on Grubhub, this is an expansion of the theory of comparative advantage. Dominos may be one of the best when it comes to pizza delivery, but even the CEO says they don’t make any money on the delivery part of their business. Their comparative advantage lies in the making of pizza, not in the delivery of pizza. Companies like Grubhub, Postmates, and UberEats have opted to specialize in the delivery aspect of the restaurant business. Ghost kitchens specialize in the production side of this delivery market.

Outsourcing a portion of the production process to someone else enables restaurants to lower their cost of production, which can be huge in a monopolistically competitive market. Gordon Ramsey is quick to point out that the “hidden” cost of a meal is rent and labor costs. Partnering with a ghost kitchen or opening a virtual kitchen allows restaurants to outsource the production side of their delivery offerings. By reducing the cost of production, firms can earn more profit per order, or they can pass those cost-savings on the customers in the form of lower prices. This would increase their sales and their profits.

The theory of comparative advantage doesn’t fit the Chuck E. Cheese experience or my quest to locate the $10 Pizza Co. It’s possible the State College option is just another example of GrubHub creating a fake listing, but Pasqually’s is a spinoff of Chuck E. Cheese. Why would a restaurant create a second operation that essentially operates as a competitor? The best answer probably lies in our understanding of monopolistically competitive markets. These markets have lots of firms selling substitutable products, like the fast-food industry:

w:User:Ross Uber, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

If a new competitor entered a monopolistically competitive market, it would slightly decrease the demand for the other firms. If we wanted to look specifically at pizza, the introduction of Pasqually’s Pizza would decrease the demand for every other pizza delivery place in the area. If there are 10 neighborhood pizza places, each equally splitting the market for pizza, they would each have 10% of the market. If one company (Chuck E. Cheese) opens what would appear to be a second restaurant (Pasqually’s), there would now be 11 companies splitting the market. Each company would now have about 9% of the overall market.

This is great news for the owners of Chuck E. Cheese because their total market share grew to 18% (Chuck E. Cheese + Pasqually’s), but they didn’t have to build a new restaurant to make it happen. Their second “location” costs some money in additional marketing and branding, but that’s relatively small compared to the cost of investing in an entirely new restaurant. Additional firms in a market should also decrease the market price of pizza in the area, which means is great news for buyers, but not so great for the other pizza shops.

While the theory of monopolistically competitive markets works to explain some aspects of the growth in virtual/ghost kitchens, it’s not necessarily good news for everyone involved. Drivers for companies like Uber Eats and Grubhub are part of the growing gig economy that has come under a lot of pressure for their work environment or lack thereof. When you purchase food through an app like Grubhub, the restaurant doesn’t receive the entire purchase price of what you paid. These considerations are more directly obvious compared to the other issues related to quick-service restaurants If you haven’t read Fast Food Nation, I highly recommend it.

If you’re intent on ordering out, the best advice I’ve seen is often to call the restaurant directly to place your order. If you’re trying to cut back on food delivery, that may be easier said than done. Either way, it doesn’t look like the virtual/ghost kitchen trend is disappearing any time soon.

Facts and Figures You Didn’t Know You Wanted

Almost half (48.8%) of Chipotle’s sales come from digital orders [Chipotle]

Dominos stores around the world sell an average of 3 million pizzas every day [Dominos]

As of May 2019, there are approximately 13,494,590 people employed in food preparation and serving related Occupations [BLS]

Americans spent $19.4 million dollars in 2019 on food delivery [US Foods]

In the United States, food waste is estimated at 30%-40% of the food supply [FDA]