Grains from Trade

With transactions complicated by sanctions, Russia and Pakistan turn to bartering, offering a modern twist that highlights the power of trade—even without cash.

Modern economies are complex, integrated, and globalized—barter seems like a relic of a simpler time. Today’s economies rely on complex financial systems, yet, recent developments between Russia and Pakistan offer a surprising throwback to this ancient practice. Faced with significant hurdles in the global financial system, these two countries have turned to barter as a temporary workaround.

The sanctions imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine have made international financial transactions far more difficult than in the past. While barter may seem inefficient compared to using money, it still provides an economic benefit to both parties, allowing them to exchange what they have for what they need, even under restrictive conditions. But how did we get here? To understand why these two are relying on this centuries-old system, it’s worth revisiting the basics of barter, why it fell out of favor, and what its temporary return reminds us about the benefits of trade.

What Is Barter?

In its simplest form, bartering is the direct exchange of goods or services without money. You’ve got something I need, and I’ve got something you want—we strike a deal, and both walk away better off. It’s as straightforward as it sounds. This form of trade was common before the invention of money. In modern economies, however, bartering is less common because money is so much more convenient.

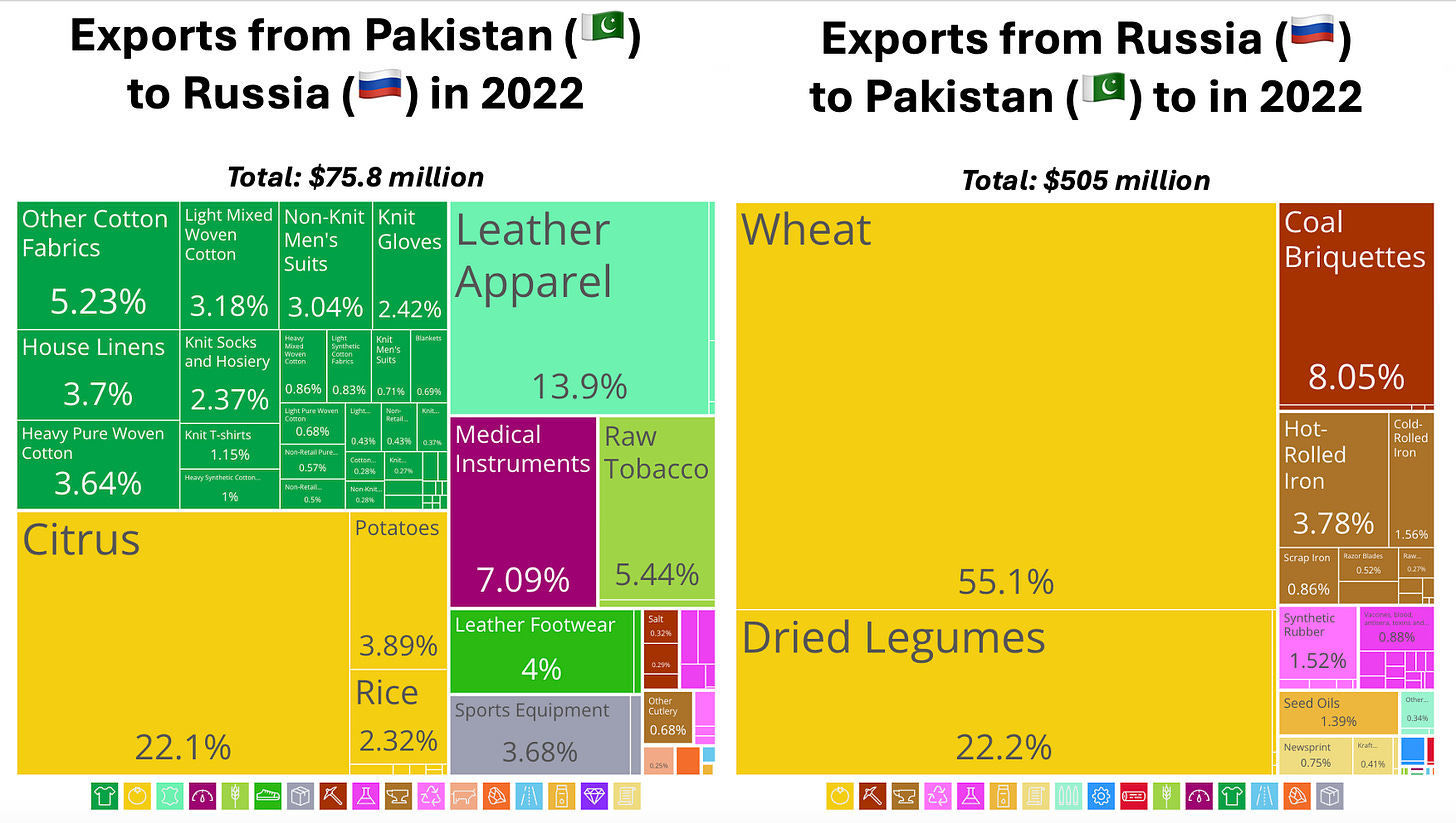

We’re seeing a return to the basics in the case of Russia and Pakistan. Russia has an abundance of chickpeas and lentils, while Pakistan has a surplus of mandarins, potatoes, and rice. Instead of dealing with the complications of cross-border payments that are hampered by sanctions, the two countries have agreed to simply swap what they have for what they need.

The Evolution from Barter to Money

Bartering was the original way humans conducted trade. If you were a farmer with extra grain, you could swap it with your neighbor who had chickens. But there’s a big challenge to this form of trade—economists call it the “double coincidence of wants.” For barter to work, both parties have to want exactly what the other has, at the exact same time, and in the right quantities. Imagine trying to trade your grain for some chickens, but your neighbor only wants to trade eggs. No trade may happen. This is what makes bartering difficult, especially when economies get larger and more complex.

Over time, societies invented money to solve this problem. Money acts as a medium of exchange, meaning you don’t need to find someone who wants your grain and has chickens to spare. You can sell your grain for money and then use that money to buy chickens (or whatever else you need). It’s a much more flexible system. Money also acts as a unit of account, making it easier to compare the value of different goods, and as a store of value, allowing people to save money for future use. That last characteristic gets a lot harder to do when you’re dealing with perishable goods like potatoes or oranges.

In short, money makes trade faster, easier, and more efficient—especially in large economies. It’s also why we don’t often see bartering on a large scale today. Even when a country’s central bank breaks down, they will often resort to a stable currency like the U.S. dollar or the Euro. But when money becomes difficult to use because of sanctions or financial restrictions, as the Russia-Pakistan agreement shows, bartering still offers a way to keep trade flowing, even if it’s not ideal.

Gains from Trade and Bartering in Difficult Times

Even though bartering can be cumbersome, the fundamental economics of trade still apply: both sides benefit. The principle of comparative advantage explains why trade works. Essentially, different countries (or individuals) are relatively better at producing certain goods than others. By focusing on what they do best and trading for what they need, they can both end up with more than if they tried to produce everything on their own.

In this case, Pakistan grows mandarins and potatoes more efficiently than Russia, while Russia is better at producing chickpeas and lentils. By swapping these goods, both countries can enjoy more variety and abundance than they could achieve through self-sufficiency. See for yourself! Russia will provide 20,000 tons of chickpeas in exchange for 20,000 tons of Pakistani rice. In another deal, Pakistan will send 15,000 tons of mandarins and 10,000 tons of potatoes for 15,000 tons of chickpeas and 10,000 tons of Russian lentils. Despite the inefficiency of bartering compared to using money, both countries are better off trading their surplus goods for what they need.

Final Thoughts

While bartering offers a temporary workaround in the face of sanctions, it’s far from a practical long-term solution. The inefficiencies that led to the invention of money—like the double coincidence of wants—make barter unsustainable in today’s global economy. Modern trade involves thousands of goods and services, and direct exchanges are complicated by logistical challenges like negotiating how many oranges equal a ton of lentils, or how to manage transport and quality control. Money was designed to streamline these processes, making trade faster, easier, and more flexible.

That said, this barter arrangement highlights an enduring truth: when traditional financial systems fail, people will always find ways to exchange what they need. Whether through digital currencies, alternative payment systems like the BRICS Bridge, or more short-term barter deals, sanctioned countries will always be on the lookout for ways to bypass economic roadblocks. In the end, even when money fails, people will always find ways to exchange goods and services.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 5,600 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

Pakistan's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2023 was $338.24 billion, approximately 0.01% of the United States [International Monetary Fund]

Knitted clothing and accessories make up approximately 16.5% of Pakistan's exports, its largest category of exports in 2022 [Observatory of Economic Complexity]

China produces 26.9 million metric tons of tangerines and mandarins each year, equivalent to 71% of the world’s production [US Department of Agriculture]

Russia produces about 31% of the world’s sunflower seed oil and sunflower seeds [US Department of Agriculture]

Yes, yes, but what's the exchange rate between chickpeas and garbanzo beans?