Cash or Cans?

Food banks are seeing an unprecedented level of demand, but what's the best way you can help?

Last April, I curled up on the couch to watch A Parks and Recreation Special. I was excited to see Leslie, Ron, and even Larry/Gerry/Terry back on my laptop. We were about two months into the pandemic, and the end of the semester is always incredibly emotional and hectic. When this tweet came across my timeline, I knew what I would be doing on April 30:

I didn’t notice it at the time, but the cast was raising money for Feeding America, a nationwide collective of food banks. I naively missed all the early stories on the pandemic’s impact and how food banks were already being stretched thin. Millions were in need of help, and many were visiting food banks for the very first time. Scenes like this one in San Antonio were common across large cities:

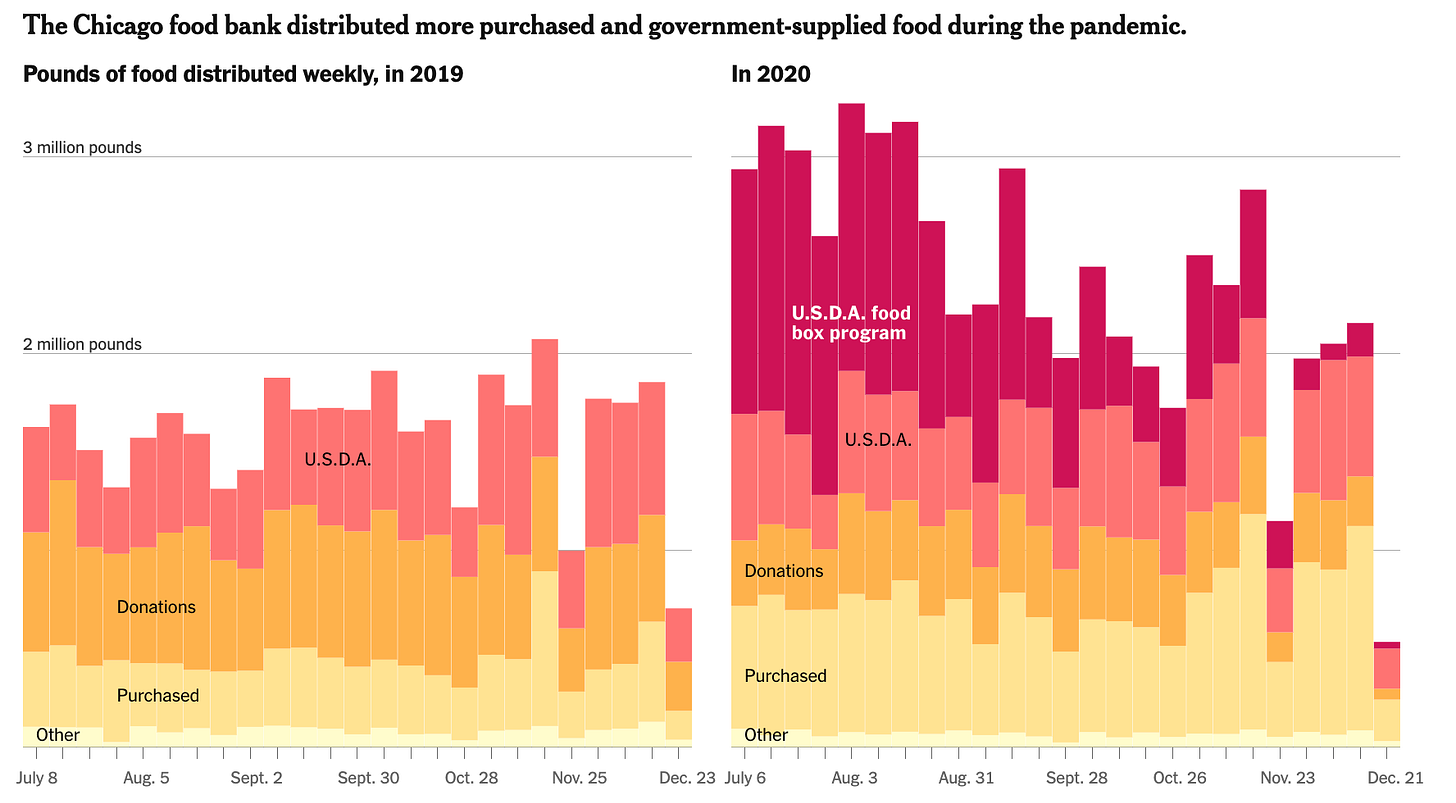

Food banks across the country served an estimated 50% more food in 2020 than they did the year before. Despite the increase in distributions over the past year, the Census estimates that roughly 8.8% of adults across the United States still report not having enough to eat over the last 7 days. Some of the largest metro areas in the US, like Houston (14.5%) and San Francisco (9.4%), are at even higher rates. Food insecurity during the pandemic was about 3 times higher compared to the year before, in spite of record distributions by food banks. Here’s a look at the Chicago food bank:

One of the big things that stood out in the Chicago food bank data was how much food donations declined during the pandemic. While millions were impacted by the pandemic, I wouldn’t have guessed physical donations would have fallen by half. I would have assumed the number would remain relatively stable or decreased slightly. We’ll talk about that purchased category in a second.

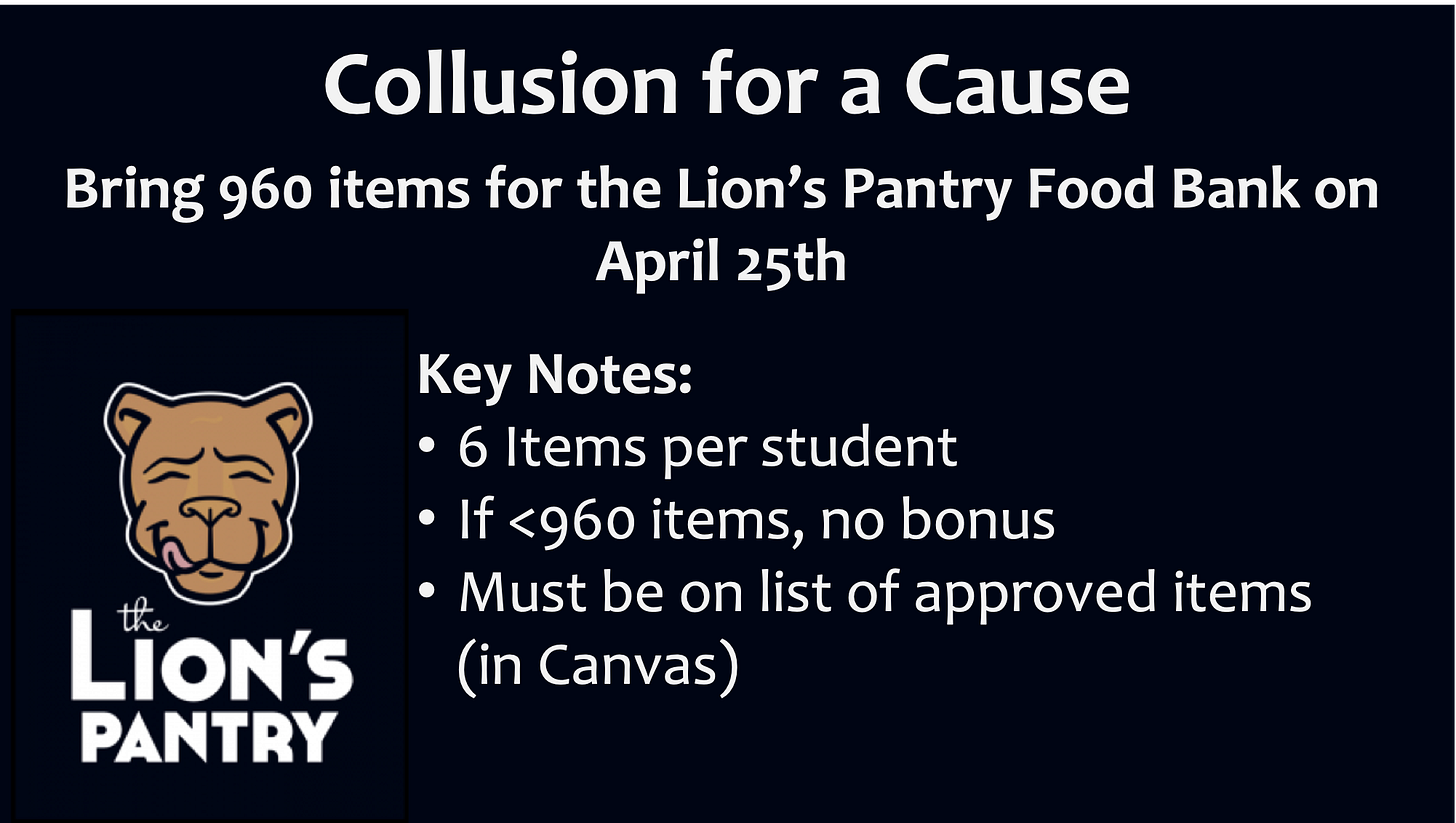

In past semesters of my principles class, I have used donations as a way of illustrating the difficulty of collusion. The last semester I did this, I had about 160 students in the class and I offered them a challenge I called “Collusion for a Cause.” Students could bring items to donate to the campus food bank on the last day of class if they wanted to. Donations were voluntary. If they collectively brought at least 960 items (6 items each) then I curved the entire class by 1%, even if they didn’t donate individually. If the class collected less than 960 items, the food pantry would still receive the donation, but my students wouldn’t receive a curve. Here’s the slide I showed 2 weeks before the last day of class:

This challenge was presented after I had talked about how collusion was difficult when there were lots of parties involved. There’s an individual incentive to free-ride and contribute nothing because other students would be nervous and bring more than an “average” amount. The worst-case scenario for a student who doesn’t donate is that they gain nothing because the goal isn’t met. They aren’t really harmed by not participating.

It turns out that the end of the semester is a really interesting time to do this because, by the last day of class, most students know their final grade and a 1% bump really isn’t much of an impact. Spring 2018 was the last time I did this experiment because it actually almost failed. We had dozens of students drop off cans/boxes as they cleaned out their dorm and cashed in their remaining meal points, but they were not close to the threshold. This was going to be the first semester they didn’t meet the goal and I was mortified to have to tell them that they collected 700 items to donate, but that it wasn’t enough.

I had rented a UHaul van to transport the items from the classroom to the Food Pantry. I learned my lesson when I was at Washington State and tried this same challenge. My small car does not appreciate the weight of that much food. Here’s a look at the back of the UHaul:

Do you notice those really big Costco boxes in the back? Those boxes are the reason my students were able to meet the goal that semester. The target was 960 items, but they ended up donating over 1,400 items to the Lion Pantry that semester. By the end of the semester, students usually have leftover “meal points” that they need to spend or else they lose them. A lot of my students used those points at the campus convenience store and donated the items to the food pantry.

One student emailed me the day before to let me know that they had told their parents about what I was doing in class and that their parents were so moved by the purpose of the project that they purchased 700 different canned goods in bulk from Costco and shipped them to their student’s dorm. A single student’s family was responsible for half of the donation that semester. They were also likely responsible for dozens of students being able to eat thanks to their generosity.

I emailed my students after I dropped off the donations and let them know they had (thankfully) failed the test of collusion. They overproduced (by a lot), just like many firms do when they collude. I told them the goal was to limit their production (to 960 items), but many of them were motivated to overproduce to ensure they individually profited. While they failed in their ability to collude, they did make a sizable donation to the campus food bank, and for that, they would all earn a 1% bonus to their grade.

There’s a second connection here that is more important, and that’s the impact of donating cash rather than physical items. While food banks may provide lists of important items to donate, people often donate whatever they have in their pantries. Even if they do buy things on the list, food banks are better informed about what items they need at any given moment. Food banks possess intimate knowledge about their space constraints and discounts from food suppliers. Feeding America, for a long time, used to distribute food based on what they thought each region needed. They became incredibly more efficient when they changed their system to focus on donating money (albeit fake) rather than trying to act as a central planner.

While Feeding America is focused on distributing massive quantities of food they receive, local food banks are also trying to meet the specific needs of their particular region. Monetary donations are more effective because it allows food banks to purchase food at a much steeper discount. Yes, food banks still have to purchase a lot of food! Your dollars have a bigger impact when you let the food bank spend them. By donating money, instead of cans, food banks can better stock their shelves with what people want/need the most, particularly perishable items like fresh produce and milk and bread.

You can think of donating cash along the same lines of gift-giving. We’ve all gotten gifts we don’t want/like, but we smile and say thank you because we know the giver has good intentions. I’m sure that’s what my local food bank did when I showed up with 1400 canned goods. Don’t worry, I did tell them I was doing this! If I had a $10 budget on getting a physical gift for a co-worker, the best I could do is get something that creates $10 of value to them. If the gift I choose isn’t worth $10 to them, then I’ve wasted some potential surplus value. If I give them $10 to spend how they choose, they know themselves better than I know them. They may need the cash more than they need a scented candle. The same thing is true for food banks:

Even in nonpandemic times, cash creates more of an impact, she said. $10 might get you a couple of canned goods and boxes of pasta at the store, but food banks can make that $10 go exponentially further. Different companies, including wholesalers, supermarkets and farmers, donate their surplus to food banks for the cost of around 20 cents per pound.

Some people don’t feel comfortable or aren’t able, to donate cash. Some donation is better than no donation at all. While cash may be the best way to donate, it’s not the only way to give. I ran a poll on my new Twitter account, and even in the middle of a pandemic, many people have found a way to donate to their local food banks:

Food banks are also in need of additional volunteers to help distribute food or prepare boxes. If you’re able, consider donating to Feeding America’s Covid-19 Response Fund. If you’re near a college campus, check and see if they have a food bank for students. If you’d like to help out Penn State students, donate to the Lion’s Pantry. If you’d like to support alma mater, Sam Houston State, check out the SHSU Food Pantry.

Food banks distributed approximately 6 billion meals in 2020, enough for every US resident to have breakfast, lunch, and dinner for 6 days [Feeding America]

An estimated 30% of college students are food insecure [College & University Food Bank Alliance]

Before the pandemic, approximately 17.5% of children in the United States are food insecure [USDA]

It’s Week 14 of 2021 and I’ve officially checked in 18 books. I read an interesting book on feminist economics, but I wish I remember who recommended it to me. The book, coincidentally, is called Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner and was thought-provoking. It covered some of the same conversations I have with students in my labor course, namely around production at home not being counted in GDP despite something of value being created.

You have made it this far, why don’t you share this post from the Monday Morning Economist with others? Hit the button below to post this to your favorite social media account or to email it to someone you think would like it: