Exports aren't counted as exports until they arrive at their destination

Containerization revolutionized international trade, but it's currently causing some major headaches around the world.

The shipping container is considered one of the major inventions that has shaped the modern world. It’s part of the reason that we’re able to consume bananas from Ecuador and shoes from China. In 1970, international trade made up about 25% of world GDP, but today it makes up close to 60%. Simply put, it’s an integral part of just about everyone’s life, and countries (even the United States) aren’t capable of producing everything it needs. When there’s a disruption in shipping channels, that can cause a major ripple throughout the world economy.

The current disruption seems to have been caused by our seemingly insatiable online shopping over the past year. “Doom shopping” during the pandemic has resulted in a surge in merchandise imports into the United States from overseas. January saw a 7% increase in the value of items imported into the US, even after adjusting for inflation. The disruption isn’t just that shipping lanes are backed up, although that is part of the problem. It turns out that US exporters (especially agriculture) are actually having a hard time sending products out of the country because shipping companies are in such a rush to get back to China that they’re sailing back with empty containers. From The Counter:

In a bizarre twist of pandemic supply-chain economics, it’s actually more lucrative for carriers to rush empty shipping containers back to countries like China than it is to wait and fill the same containers up with American ag exports.

They’rerushing to get back because Americans need those imports and Americans import a lot of really different things. The Observatory of Economic Complexity tracks international trade in a variety of ways, but this treemap is my favorite. In 2020, the US imported $1.94 trillion worth of products. Here’s the breakdown of what came in:

So what’s happening in North American shipyards? While Americans are buying more imported products than they have in the past, labor shortages on the docks mean that it’s taking a lot longer to load and unload those containers. Longshore workers are experiencing the same COVID surge that others have also been facing. The labor issues extend north of the border as Canadian longshore workers are threatening to strike over their expiring collective bargaining agreement. Shipping issues facing the global supply chain from the United Kingdom to South Africa to Panama. The pandemic has created a perfect storm of logistics issues:

You have pent up demand in Asia for agriculture products and that’s at the same time you have a pretty substantial consumer goods demand in the U.S. When you add to that some of these labor issues, that’s what really crated the scarcity you are seeing.

This isn’t just a weird quirk where a few more ships are being sent back empty, and we’re just now noticing. According to data compiled by the US Census Bureau and major ports in California and New York, carriers rejected almost 178,000 containers in October and November of 2020. The total value lost at those ports is estimated to be around $632 million.

This behavior is also hitting American farmers hard. The United States exports food every month of the year, but November through March are critical months. Because the Chinese economy has recovered from the pandemic much faster, Chinese exporters are paying premiums for shipping containers to come back as quickly as they can, which means coming back with empty containers. Chinese exporters are willing to pay premiums for ships to come back faster because delays in shipping can be costly. An AER study from 2013 estimates each day in transit is equivalent to a 0.6 to 2.1 percent tax on the products.

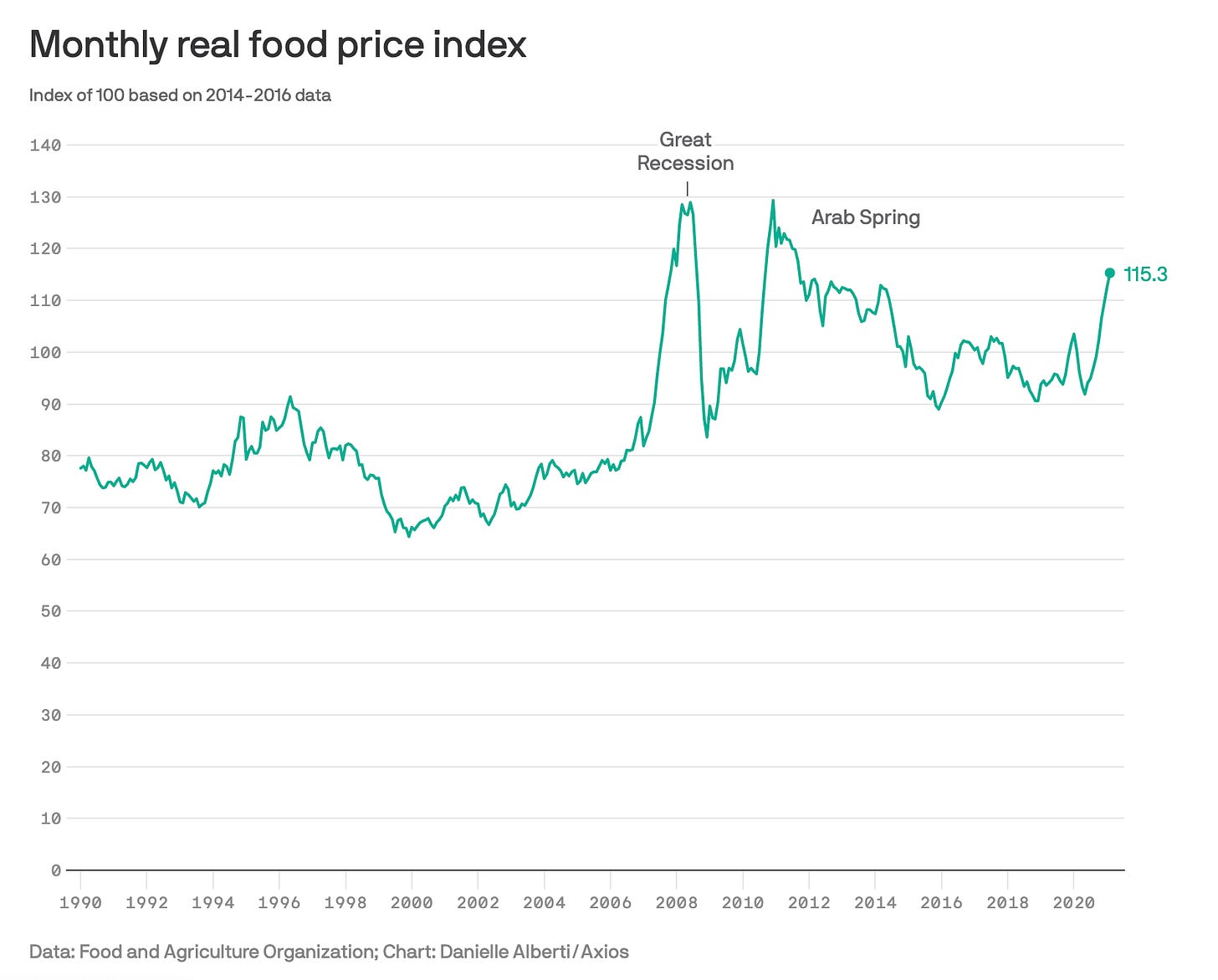

Because Chinese exporters are willing to pay premiums for shipping companies to come back empty, this has led to increased shipping prices for everyone. In December, spot freight rates were up 145% from the year before on routes from Asia to the West Coast. Shipping costs are just one of the many input costs that impact the final price of the products we buy. This has big more obvious impacts on e-commerce companies and consumers, but it also affects global food prices. In February, world food prices increased for their 9th consecutive month and hit a 7-year high.

The solutions? In the short term, it looks like there is a push for regulators to intervene. It may be a violation of the US Shipping Act for carriers to “unreasonably refuse to deal or negotiate.” Exporters have limited other alternatives to getting their projects out since the only real alternative for overseas exports is air freight. That usually requires empty space in passenger planes and we’re still not back to flying regularly yet. A more long-term solution is happening as logistics companies race to build more containers. It’s not clear how long this could take since the pandemic has also hit the steel and lumber industry as well.

Facts and Figures You Didn’t Know You Wanted

A standard shipping container is 20 feet long and has a volume of 405 cubic feet [Falcon Structures]

In January 2021, the US imported $219.8 billion worth of products into the country [US Census]

95 percent of overseas moves into the US by ship [US Army Corp of Engineers]

Sellers on the Amazon marketplace sold $300 billion worth of merchandise, which is more than the GDP of countries like South Africa, Finland, and Colombia [Marketplace Pulse]

Agriculture, food, and related industries contributed $1.109 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product in 2019, a 5.2 percent share [US Dept. of Agriculture]