Why Are Eggs So Expensive While Chicken Prices Stay Flat?

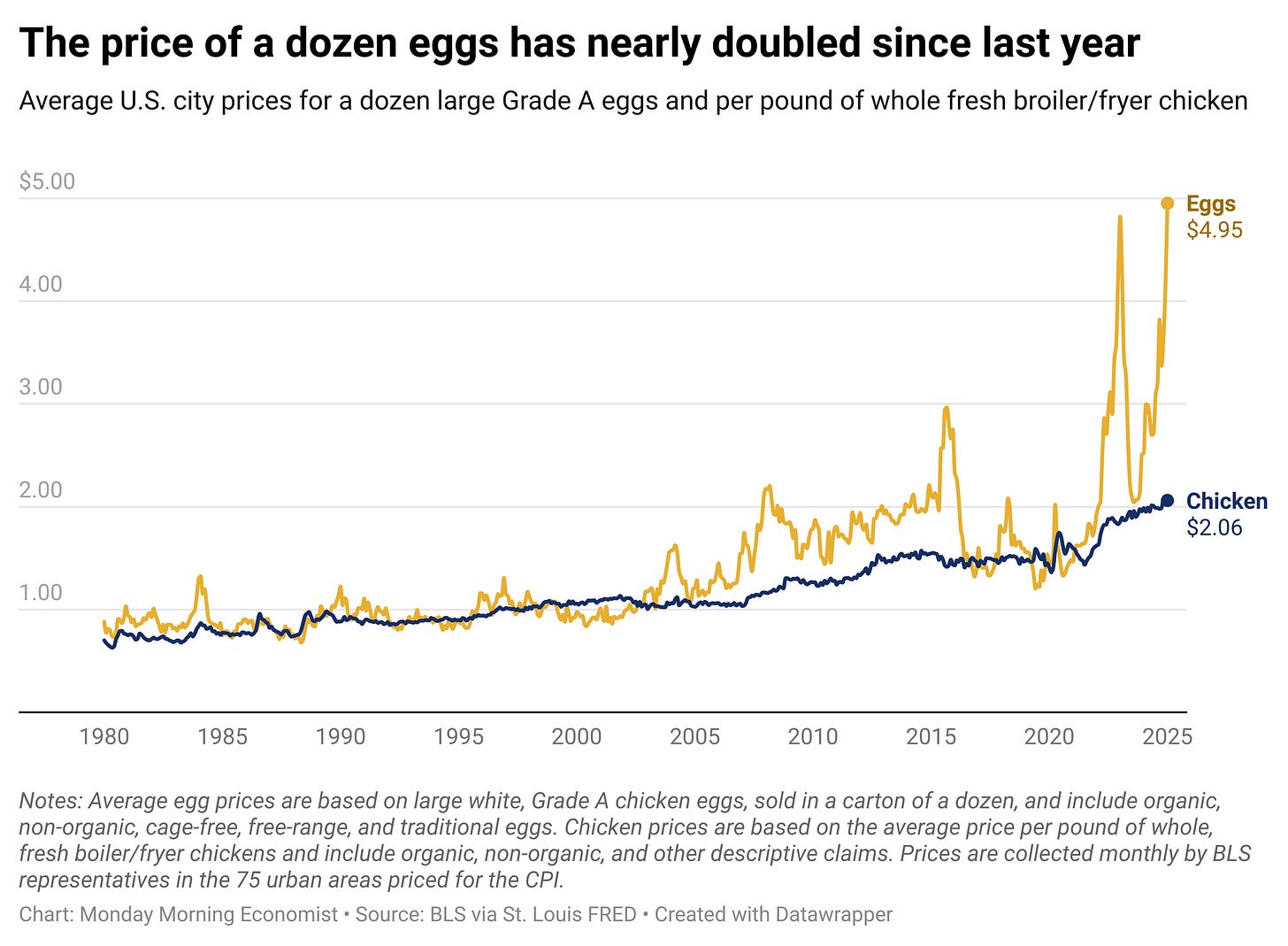

Egg prices have skyrocketed due to a bird flu outbreak, but the price of chicken has remained relatively stable.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

How well do you remember your last trip to the grocery store? If you were like me, you wandered over to the egg section hoping that prices had finally come back down—but they hadn’t. For the past two years, eggs have been stubbornly expensive. The problem has gone on for long enough that some stores have started limiting the number of cartons customers can buy, and in some places, panic buying has made the shortage worse.

But while you were frustrated with the price of eggs over the past few years, you may not have realized that the price of chicken meat hasn’t changed by nearly as much. That’s strange, isn’t it? A bird flu outbreak has led farmers to cull millions of chickens—so why hasn’t it affected the price of chicken in the same way that’s impacted eggs?

The answer lies in an economic concept known as the elasticity of supply, which describes how quickly farmers can replace what they’ve lost.

The Bird Flu Shock

We’ve known for a while now that bird flu has been the main cause of rising egg prices. But what you might not have realized is that not all chickens have been affected equally.

There are two main types of chickens in commercial production: egg-laying hens, which produce eggs over a long period, and broilers, which are raised for meat. Bird flu has impacted both flocks, but the scale of the damage has been wildly uneven.

The outbreak has wiped out millions of birds over the past few years—but more than 75% of the losses have come from egg-laying hens, compared to just 9% from broilers. It’s no wonder then that the supply shock in the egg market has been much more severe than in the broiler market. But the drastic change in prices isn’t just because of a larger supply shock. Egg-laying hens also have a more inelastic supply, which means it takes far longer to replace an affected flock.

Let’s talk about why that matters for prices.

Elasticity and Price Changes

Even if bird flu had wiped out an equal percentage of egg-laying hens and broiler chickens, we’d still expect egg prices to increase more than broiler prices. Why? Because the supply elasticity—or how quickly farmers can replace lost chickens—is dramatically different between the two.

Elasticity measures how easily producers can adjust the quantity supplied in response to changes in the market. When supply is inelastic, it’s more challenging to quickly recover from a disruption. This means a relatively small reduction in supply can increase prices by a whole lot more. When supply is more elastic, producers can respond quickly to market changes. This keeps prices from increasing too much.

Egg-laying hens take four to five months to mature before they start producing eggs, and their production cycle can last more than a year. But if a flock needs to be culled, it can take nearly half a year to get back to the same level of production level.

Broilers, on the other hand, grow much quicker—reaching market weight in under two months. If a farmer loses its flock of broilers, it can replace them nearly twice as quickly compared to the hens in an egg facility. This keeps the chicken meat supply much more constant and prevents major price swings.

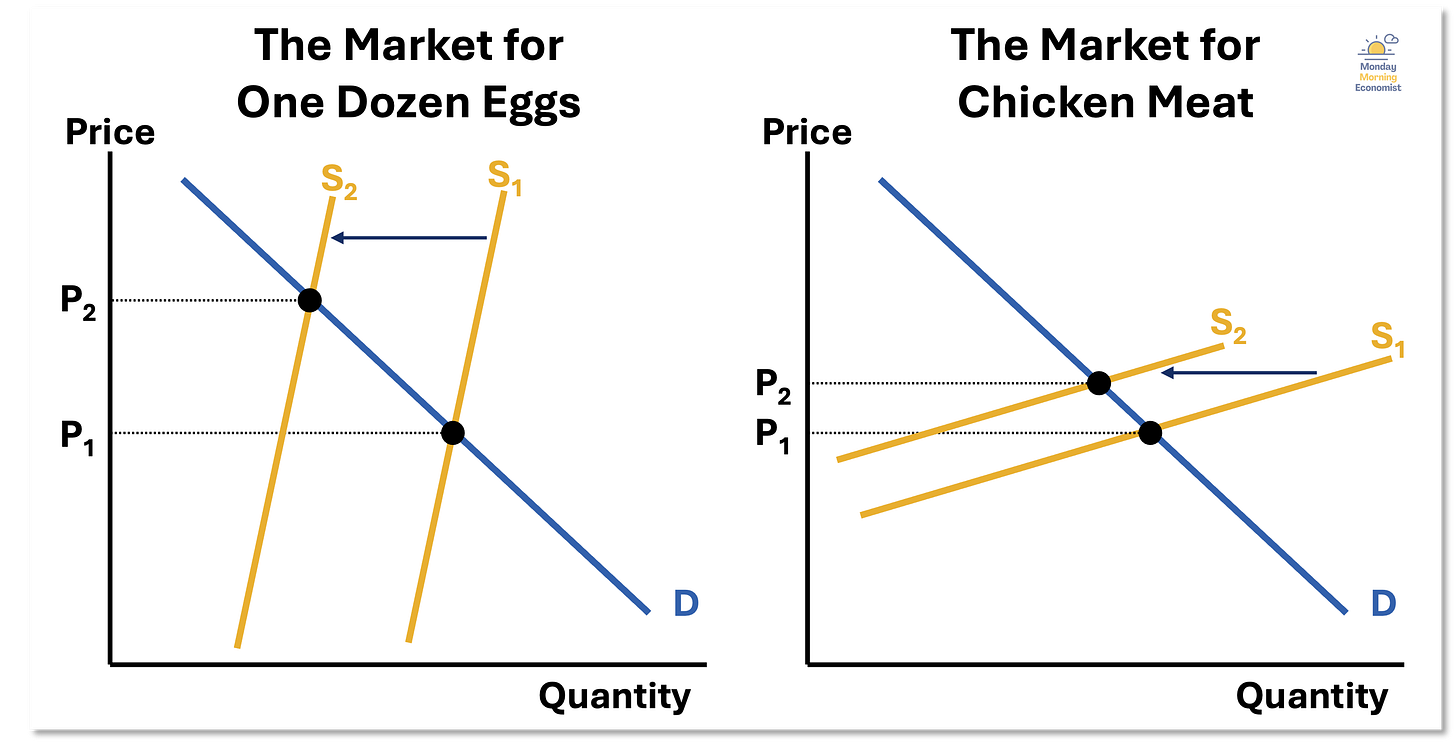

If you’re more of a visual learner, you can see how supply shifts affect market prices in the charts below (Hint: it’s not good news for egg buyers!). In the market for eggs on the left, the supply line is much steeper, indicating a relatively inelastic supply. In the market for broilers on the right, a relatively flat supply line indicates a market that is much more responsive.

The same-sized supply shock doesn’t have the same impact on prices or quantity. When supply is inelastic, price increases are more severe. While we’re focused on the prices, you’ll also notice the change in quantity is more pronounced in the egg market. This helps explain why we’re seeing shortages in the egg cases but not at the butcher counter.

Keep in mind that the supply shock hasn’t been the same. The two charts above show the same-sized shift, but egg-laying hens have been hit much harder than broilers. That means we’re seeing even higher prices for eggs because of their inflexibility, but also because the supply shock was much larger.

That’s why the price stings a bit more when you’re reaching for eggs, but not when you buy chicken. Over the past year, egg prices have surged by 96%, while chicken meat prices have barely moved, rising by less than 4%.

Final Thoughts

Although we’ve focused on the supply side of these markets, consumer responsiveness has made things worse as well. Eggs have historically had pretty inelastic demand relative to chicken. This means people buy roughly the same amount each week regardless of the price because there aren’t many good substitutes. It’s hard to swap out eggs one-for-one in baking and they’re (historically) a cheap staple for many households. So when prices have increased, the quantity people purchase doesn’t fall by much and prices tend to stay high.

Chicken meat, on the other hand, has several appropriate substitutes—beef, pork, turkey, and even plant-based proteins. If your butcher were to increase the price of chicken breasts and thighs, you could more easily shift your spending to a different protein. This helps keep price increases in check.

If you’re more of a cold breakfast person, you might not care much about the price of eggs. And you’re in luck! The USDA expects egg prices to remain high in 2025. If the outbreak slows, however, supply could recover and prices could come down like they did in 2023. Unfortunately, if eggs are a big part of your weekly grocery list then you’ll probably be feeling the pain for a while longer.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 6,600 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

Americans consume about 280 eggs a year, more than half an egg per day [NPR]

There are more than 378.5 million egg-laying chickens and more than 9.4 billion broiler chickens in the United States [U.S. Department of Agriculture]

Since the current strain of bird flu (H5N1) reached the United States in 2022, over 148 million birds have been ordered euthanized [CBS News]

Since October 2024, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported a 29% increase in egg seizures at the U.S. borders [Global News]

The edible part of a chicken's egg is approximately 74% water, 12% protein, and 11% fat [Oklahoma Ag in the Classroom]

I’m getting evaluated today at the community college. My lesson is going to be on elasticity, I feel like you just gave me a secret weapon. Can't wait to share it with my students!

Great analysis! I was about to comment on the demand side before I got to your final thoughts! It's really a tough time for us egg eaters!