A Timely Discussion on Unintended Consequences

Daylight Saving Time was intended to improve electricity usage, but those benefits have become suspect. The unintended consequences, however, of such a policy have continued to grow over the years.

Sunday morning may have been the first time many people across the United States got a full night’s rest. In 48 states and DC, Daylight Saving Time officially ended, which meant Sunday gave most of the country an extra hour to rest since the change came at 2 AM. Many of us got a sunnier morning to enjoy our cup of coffee, but it also means a lot of us will end up with a darker commute home later today.

Political leaders have debated the tradeoffs of time shifting for centuries. Benjamin Franklin (jokingly) suggested that the French could save money on candles if they took advantage of early sunlight. He knew people would be unhappy about the change and recommended taxes on window shutters, rationing candle sales, and eliminating non-emergency coach traffic after dark. It wasn’t until World War I that US politicians started to seriously consider it as a way to preserve fuel.

In 1918, Congress included a Daylight Saving Time clause in its time zone legislation. The Standard Time Act of 1918 mandated federally designated time zones across the country and initially called for Daylight Saving Time to begin on March 31. Despite modeling it after other countries that had already made the shift, American farmers weren’t thrilled, and that portion of the legislation was removed.

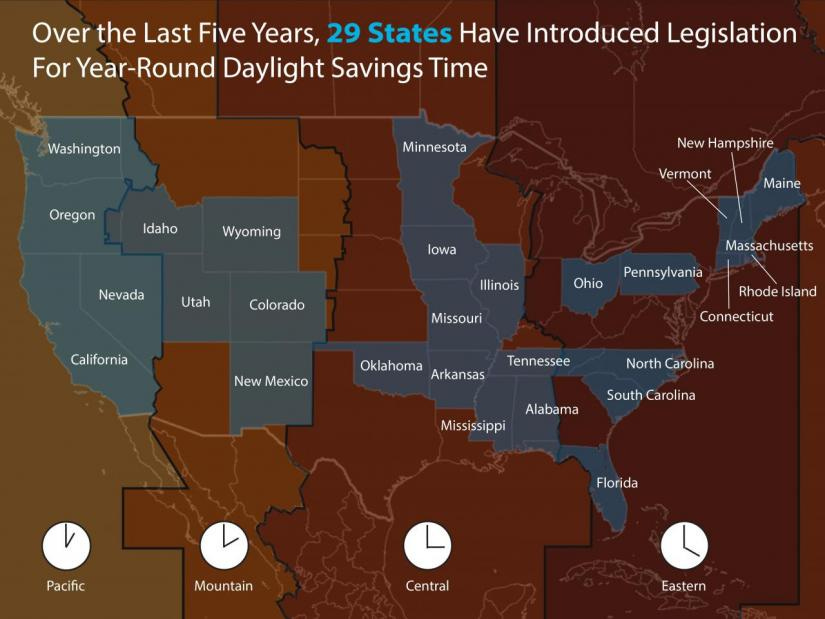

Congress went back and forth over the next few decades but eventually mandated the system federally under the Uniform Time Act of 1966. States were able to exempt themselves from observing Daylight Saving Time, but they could not change the start and end dates from the federally mandated dates. Over the past few decades, a number of states have introduced legislation for year-round Daylight Saving Time if the Department of Transportation would ever allow it.

When our clocks change in November, we typically celebrate because we get an extra hour of sleep. In the Spring, however, we’re often miserable because we’ve lost an hour. We all face tradeoffs in decision-making, and deciding whether to stick with Daylight Saving Time or Standard Time is just one of the many choices politicians try to make. You can actually use this neat online tool to see which policy would benefit you the most.

The intention of Daylight Saving Time (which is officially the period from March to November) was an environmental one: cut down on energy costs. It turns out that the retail industry is also a big proponent of the program since people are more likely to shop if they have more sunlight after work. The environmental benefits may have been more significant in the early 1900s, but the results aren’t as convincing today.

Lighting costs are still a component of household energy usage, but electricity usage has been heavily influenced by the pervasiveness of air conditioning and other household electronics. In a 2011 study of Indiana’s shift to statewide Daylight Saving Time (it was previously county-specific), researchers found that electricity usage increased as people decreased their demand for lighting and increased their demand for heating and cooling.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 changed the official start and end dates of Daylight Saving Time to what we know today. In a 2008 report to Congress, analysts at the US Department of Energy found that the four-week extension of Daylight Saving Time saved about 0.5% of the nation’s electricity usage each day. This would have been equivalent to powering 100,000 households per year. A 2017 analysis of 40+ papers on the subject found that Daylight Saving Time saved an average of 0.34% of electricity use. Places further from the Equator might save more energy, but places closer to the Equator use more energy.

While the benefits of daylight saving are negligible, there have been a number of unintended consequences from the policy. Early philosophers like Adam Smith and John Locker discussed how purposeful action may result in outcomes that were not intended or could be predicted, but the concept has been popularized more recently. To help save on space, I’ll link out to some of the unexpected costs of switching between Daylight Saving Time and Standard Time so that you can investigate the ones you’re most interested in learning more about:

Workers lose an average of 40 minutes of sleep when the clocks change back in the Spring.

Some researchers have suggested that changing clocks leads to increased stock market volatility.

In March 2022, the Senate passed the Sunshine Protection Act, but it is currently stalled in the House. The Act intends to make Daylight Saving Time permanent, but the US already tried this in 1974 and it failed miserably. The public backlash was severe enough that Congress passed an amendment to end the experiment after just four months. A House panel noted that energy savings, “must be balanced against a majority of the public’s distaste for the observance of Daylight Saving Time.” It turns out that the majority of Americans can’t even agree one way or another on Daylight Saving Time.

The average American adult with kids in the house sleeps 8.76 hours per day while those without kids sleep an average of 8.97 hours per day [US Bureau of Labor Statistics]

Daylight Saving Time is not observed in Hawaii, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and most of Arizona [US Department of Transportation]

A March 2022 poll found that 46% of U.S. residents preferred daylight saving time all year round, 33% preferred standard time year-round, and 21% were okay with continuing to clock switch twice a year [CBS News]

The Uniform Time Act of 1966 passed the House of Representatives with a vote of 292-93 [GovTracker]

The earth turns on its axis at a relatively constant 23.4-degree angle relative to its path around the sun [National Geographic]

BONUS: For a little fun on the intersection of economics and Daylight Saving Time, I got a chuckle out of this tweet: