May the Economic Force Be with You

Deciphering sunk costs and opportunity costs through Disney's to close its costly Star Wars adventure hotel

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

In the galaxy of economics, rational decision-making is like charting a course through the stars. It's a journey fraught with choices, balancing costs and benefits in the pursuit of maximum gain while avoiding the heavy pull of losses. And yet, there are two concepts that often shape these economic decisions.

We must ignore the pull that one cost has on us while carefully considering the impact that the other cost has on our decisions. The problem? It’s really easy to focus on the one we should ignore and easy to forget about the one that can have the most profound impact on whether we’ve actually made the right choice.

Let’s explore these two concepts through the lens of a real-life Star Wars adventure—Disney's decision earlier this summer to close the Star Wars Galactic Starcruiser in Orlando after only 18 months of operation. During Disney’s third-quarter earnings call earlier this month, the company revealed that the closure would result in a $250 million loss. Thankfully, this economics lesson will be much cheaper for you.

Before we get too far into this one specific case, I’d be remiss if I didn’t share some amazing resources that link Star Wars to other economic concepts. Matt Rousu (#Econtastic!) and colleagues developed the Economics of Star Wars website, which includes scenes from across the franchise that demonstrate different concepts. Economics Explained has a great video on the economy of the Star Wars galaxy and ACDC Econ has a video that looks at a few key concepts in Star Wars:

Some Context on the Galactic Starcruise

This is the story of a hotel. A very special hotel known as the Galactic Starcruiser Hotel. It's like an escape room on steroids, a live-action role-playing game, and a high-end hotel all wrapped into one. It's designed to make you feel like you're in the Star Wars universe. It’s not clear exactly how much Disney spent to build this hotel experience, but it likely cost somewhere around $350 million.

Just to give you a sense of the experience, here's what it's like when you first arrive. You enter a huge building that looks like a warehouse from the outside, but inside, it's a completely different world. There's a main atrium, a bar, a dining room, a gift shop, and unique “Star Wars” spaces like a spaceship bridge and a lightsaber training room. A two-night stay for a couple initially started at around $5,000 when the hotel opened in March 2022, but the price tag eventually fell to around $1,600 as Disney struggled to fill the 100-room hotel.

Keep in mind that this isn’t just a hotel, it's an experience. There's a complex narrative going on all around you. You're not just a guest; you're a character in the Star Wars story. There are lifelike characters walking around. The food and drinks are all Star Wars-themed. When you arrive, you're told that you're on a voyage across the galaxy aboard a luxury starcruiser. You can explore the ship, interact with the characters, and even participate in activities like lightsaber training.

But here's the thing: Disney had to make a really tough decision about the Starcruiser. It was losing a lot of money. Like, $250 million a lot. Knowing that now helps explain two fundamental ideas in economics: sunk costs and opportunity costs. The significant price tag likely left some Disney executives at a crossroads when trying to figure out what to do with this hotel that was struggling to turn a profit. Should they hold out a little while longer in the hopes that people would shell out the money to stay at the site, or was it time to cut their losses and move on?

Sunk Costs: The Price Already Paid

Sunk costs are like the ghostly echoes of the past, haunting decision-makers like the Force ghost of Obi-Wan Kenobi. If that reference was too specific to Star Wars, you can think of sunk costs like the pull of a black hole. It’s the money you've already spent, and you can never get it back. In Disney's case, a sizeable sunk cost was clearly present when it decided to close the Star Wars Galactic Starcruiser hotel.

It’s easy to see why a company might want to keep trying to make money after spending so much money. When you're in the middle of a big project, it can be hard to see those past investments as sunk costs. You're invested. You've put in a ton of time and money. It feels like you've come so far to just quit now.

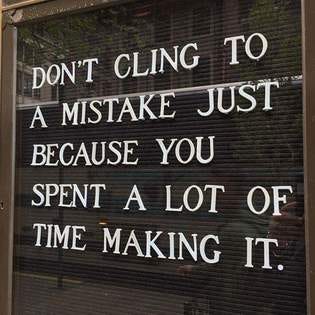

But, sometimes, the best thing to do is to recognize that it's over. Sunk costs can be really hard to let go of, especially when they're big. But the thing is, they should be ignored. The sunk cost fallacy is our tendency to continue doing something just because we've invested money, effort, or time into it—even if the current costs outweigh the benefits.

That's why it's so important to keep in mind the other concept that’s harder to think about, but ultimately more important in decision-making: opportunity costs.

Opportunity Credits: The Cost of the Uncharted Lane

Opportunity costs are like the stars in the night sky, always there, but not always easy to see. In our vast economics universe, opportunity costs are how decision-makers value paths not taken. It’s a measure of the next best alternative foregone when a decision is made. To grasp the concept, consider what Disney could do with the resources it would save by closing the Starcruiser hotel.

It was clear early on that the Starcruiser Hotel was losing money, and continuing to operate the hotel would likely result in further financial losses. These losses are just some of the opportunity cost of keeping the venture afloat. Opportunity costs extend beyond the financial realm. They include the potential to invest in new attractions or expand existing ones.

So, Disney had to weigh the sunk costs of the Starcruiser against the opportunity costs of keeping it open. This is where things get tricky.

The Decision-Making Dilemma: Jedi Wisdom in Economics

The sunk cost fallacy is like the dark side of the Force, it’s seductive and powerful. It often traps decision-makers into irrational choices, compelling people to hold onto bad investments simply because they've invested heavily in them. It’s that feeling of, “I’ve already spent so much money on this, I can’t quit now.”

You’ve likely done this yourself as you sit through a bad movie to the end simply because you paid for a ticket. If you were watching the same bad movie on Netflix, you likely wouldn’t think twice about closing your laptop. The opportunity to do something else is similar in both scenarios, but the pull of that sunk cost is just so strong. It’s simply easier to justify the continued action when you know how much you’ve paid for it.

That's what makes the sunk cost fallacy so dangerous. It can lead people to throw good money after bad, chasing losses and making irrational decisions. The more challenging decision is to recognize that money is gone. For Disney, that means acknowledging the decision to move on will cost them $250 million dollars of accelerated depreciation. By admitting defeat, it allows them to focus their future energy and effort on other, more profitable ventures.

While none of us were in the room when the decision was made, there were likely some executives who argued that Disney had invested too much in the project to back out. That way of thinking only sounds logical despite not actually being so. Sure, the loss is tangible and substantial, but by deciding to focus on the future instead of the past, Disney's leadership has embraced the Jedi teachings of Master Yoda - "You must unlearn what you have learned." Making decisions based on past investments would only lead to financial ruin.

Decisions should be made by weighing the benefits against opportunity costs, not sunk costs. Instead of dumping more and more money into the Starcruiser hotel to attract more guests or attempt to make the venture profitable, Disney instead considered what else they could be doing with that money. In hindsight, this is a really obvious choice.

The problem facing most decision-makers is that opportunity costs are often implicit, while sunk costs are explicit. It’s much easier to read the receipts of the sunk costs you’ve spent, but it’s much harder to calculate the opportunity costs of what you could be doing instead. In this case, the economic choice won out. Unfortunately, that isn’t always as common as it should be.

The Economic Force of Everyday Life

While Disney's Starcruiser saga provides a timely example of accurately avoiding the sunk cost fallacy, the rest of us may not be so quick to make the right choice. Sunk costs and opportunity costs are present in our daily lives, and they influence our decisions more often than we might realize:

Imagine you’ve recently purchased a new laptop, but a more advanced one becomes available that better suits your needs. The cost of the first laptop is a sunk cost. The opportunity cost of continuing to use the one you purchased is the power and capabilities of the new, more advanced laptop. If the new one suits your needs better, continuing to use the old one because “you already spent $1,000 on it” is an example of falling for the sunk cost fallacy.

Business owners face a similar dilemma when trying to decide whether to invest in new equipment or perhaps change up their marketing campaigns. While some things may be able to be resold or repurposed, some portion of that money and time is gone forever. Instead of sticking with a marketing campaign because they spent so much time designing it, it’s better to weigh the opportunity costs associated with changing the message.

And finally, I’ll share one near and dear to my heart as an educator. Students often question whether they’ve picked the right major, and switching degree programs as a junior or senior is often discouraged. People look back on all the years spent studying for one program and consider it a waste to switch majors to a potentially more fulfilling program. They finish out a degree in a subject they don’t enjoy because they spent a bunch of time on it already.

In each scenario, recognizing the distinction between sunk and opportunity costs empowers us to make decisions aligned with the Jedi Economist’s guidance. Our choices should be influenced by future potential rather than past investments. Armed with the wisdom of distinguishing between what's already spent and what could be gained, we can chart a course toward a more prosperous future that’s not so far, far away. If Disney can admit defeat and lose $250 million, perhaps we too can harness the power of economics to make decisions that are far less costly. May the (economic) force be with us all.

Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope was originally released on May 25, 1977 and has sold an estimated 178,119,500 tickets [Disney | Box Office Mojo]

The Disney World resort employs around 77,000 “Cast Members,” which makes it the biggest single-site employer in the United States [Magic Guides]

Galactic Starcruiser hotel had 100 rooms, accounting for about 0.5% of all of Disney's hotel room inventory [Fox Business]

Harrison Ford was paid only $10,000 (around $50,400 adjusted for inflation) for his role in the first film [Parade]

Star Wars: Episode VII - The Force Awakens has earned $2,071,310,218 since its debut in 2015 [Box Office Mojo]

Bonus Chart

This didn’t really fit with anything in the story, but I figured you’d want to see it anyway. Here are the top 20 grossing films of all time, adjusted to 2022 ticket prices.

Behold! If they had made it more like an actual cruise, and used the 'excursions' to the 'planets' as the focal point for the adventures, it probably would have been much more successful.

Once you get how our income-based labor force really works (that high profits depend on low wages), you will finally see and understand all the reasons why a global system that can match people to jobs, resources to communities, and everyday needs and demands to local production, consumption, and recycling operations is more sustainable and ethical than monetary methods practiced today, mainly because scientific-socialism, compared to scientific-capitalism, is actually more democratic; it values and views this very basic, very intuitive belief “universal protections for all” as both a human and environmental right.