What Can the World’s Largest Cruise Ship Teach Us About Economics?

We're embarking on a journey that's not just across the ocean but also through some fascinating economic waters.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 3,700 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

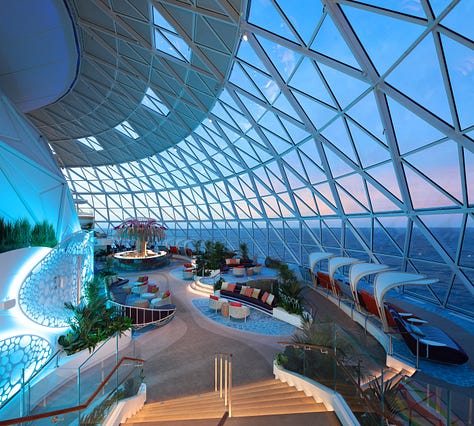

Royal Caribbean’s latest megaship, Icon of the Seas, set sail on Saturday out of the port of Miami on a week-long tour of the Caribbean. This ship isn’t just big; it’s record-breaking big. We’re talking a 20-deck, approximately 1,200-foot-long floating city, boasting 40 restaurants, 7 pools, and yes, for those looking for a bit of intrigue, an escape room.

But this isn’t just a story about luxury and leisure. This colossal vessel, packed with nearly 10,000 passengers and crew, is a living, floating lesson in economics. As it slices through the waves, every deck, every suite, every bustling kitchen, and humming engine room operates on two pivotal economic principles that are essential for turning a profit in the high-stakes world of cruise liners. All aboard!

Managing a Floating Metropolis

As we make our way on board the bustling decks of the Icon of the Seas, every corridor, kitchen, and cabin crew operates with a special kind of precision. This isn’t just about keeping things tidy; it’s about the art and science of efficiency and specialization. So, what do these terms mean in the context of a gigantic cruise ship?

Efficiency, in economic terms, is about maximizing outputs from given inputs. The ship’s crew is playing a game of resource Tetris, where every block of food, water, and energy needs to fit perfectly to avoid waste and optimize use. On ships like Icon of the Seas, this game reaches a whole new level. Cruise ships rely on a high degree of specialization among crew in order to maximize output on their voyage.

Take the culinary team, for instance. On a typical seven-day cruise, a ship’s guests and crew can churn through tens of thousands of pounds of food and beverages. It’s a dining marathon that requires more than just a big fridge and a lot of pots and pans. Here, efficiency is critical to ensuring thousands of guests are fed within just a few hours. Specialized chefs might spend hours plating just one type of pastry served for during dinner. This level of specialization ensures each chef is an expert in their domain, churning out culinary masterpieces with minimal waste and maximum productivity.

Specialization and efficiency don’t just apply to what’s cooking in the kitchen. There is a similar level of specialization occurring with housekeeping and cabin steward. Unlike your typical hotel on land, cabin attendants on cruises are assigned a smaller number of rooms. They aren’t taking it easy. This approach allows for personalized service, paying attention to the smallest detail in each room and catering to each cabin’s needs.

This focus on operational efficiency and specialization isn’t just a cruise ship thing; it’s a global corporate objective. From Silicon Valley to Wall Street, the push for doing more with less is what keeps the companies afloat. Whether on board a floating city or in a corporate office park on the outskirts of a city, every drop of efficiency counts.

The Bigger, the Better?

The crew is in place, the captain is on the bridge, and now it’s time for the guest to board. For cruise ships this size, it’s important to get as many people on board so the ship can take advantage of what economists know as economies of scale. Running ships like this are far from cheap. We’re talking about enormous fixed costs here—docking fees, crew salaries, and the energy to power this beast. Megaships like this one operate at an estimated cost of around $920,000 each day. Sounds unprofitable? Here’s where economies of scale sail to the rescue.

Icon of the Sea can accommodate up to 7,600-passengers on this behemoth. The more cabins that Royal Caribbean can sell before disembarking, the lower the cost per passenger. To make the economics work, ships need to be bustling with guests. This is why newer cruise ships are packed full of all sorts of different amenities.

To attract a diverse range of passengers and ensure the ship sails at near-maximum capacity, Royal Caribbean has decked out the Icon of the Seas with attractions galore—escape rooms, pools, and a smorgasbord of dining options. It’s all about appeal and variety. It’s unlikely that any one guest will attempt to visit every attraction, but there’s likely something on board the ship for everyone.

If a cruise ship only had pools and bars, they no longer appeal to guests who want kid-friendly activities and shows. All these amenities aren’t just perks; they’re chosen to draw in guests. And once on board, they can then focus on earning additional revenue in other ways. My friendMatthew Rousu highlights some of the ways cruise ships take advantage of price discrimination to extract more money out of guests:

Navigating Towards a Greener Future

As we near the end of our journey aboard the economic ocean liner, there’s one more crucial port of call: the environmental impact of these floating giants. It’s an often troubling part of the story that we can’t simply sail past. With great size comes great responsibility, especially towards our planet. Historically, the wake left by these luxury liners has been marked by significant carbon emissions and a worrisome impact on marine ecosystems. They’re like floating cities, and just like cities on land, they leave an environmental footprint— sometimes, a heavy one.

That narrative is changing, albeit slowly. Icon of the Seas is set to be powered by liquefied natural gas, or LNG. It’s no magic bullet, but it’s a step forward. It burns cleaner than traditional fuels, reducing emissions that contribute to air pollution and climate change. It’s part of a broader attempt to chart a more sustainable course in an industry historically powered by less eco-friendly means.

But let’s not sugarcoat it. Despite these improvements, the overall environmental impact of cruise ships, particularly the largest ones, remains substantial. So, as the Icon of the Seas vanishes over the horizon, it leaves us with a rich set of economic lessons. This ship is more than a vacation destination. It’s a floating classroom where economics and innovation intersect.

At the end of 2024, the total worldwide ocean cruise capacity will be 673,000 passengers and 360 ships [Cruise Market Watch]

Feeding around 8,800 passengers and crew on a typical seven-day itinerary requires some 60,000 eggs, 9,700 pounds of chicken, 20,000 pounds of potatoes and 700 pounds of ice-cream [CNN]

85% of cruise passengers say they’d go again [Cruise Lines International Association]

Posts about Royal Caribbean’s 9-month cruise have more than 350 million views on TikTok [Vox]

Cruise ship emissions are up 6% from before the pandemic [Climate TRACE coalition]

A five-night, 1,200-mile cruise generates about 1,100 lbs of CO2 emissions, while flying the same distance and staying in a hotel would emit less than half of that [TIME]

Is the CO2 emission, per passenger, better on a single large ship or several smaller vessels?