New York City’s Road to Congestion Pricing Looks a Little Less Crowded

The FHWA approval brings congestion pricing in Manhattan closer to reality, with vehicles entering below 60th Street facing a fee, although the exact payment structure is not yet know.

New York City's long-awaited congestion pricing scheme has overcome a major hurdle as the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) granted near-final approval for tolling motorists who drive in Manhattan below 60th Street. This development marks a significant step forward in implementing the program, which was initially approved four years ago for a subset of drivers in the Big Apple. The recently announced requirements provide more clarity on how the tolling process operates and sheds some light on various economic principles at play.

Traffic congestion is a classic example of negative externalities. Individuals make decisions about whether to drive based on their own costs and benefits, but when too many people hop in their cars to drive to work, the roads become congested. This congestion imposes a cost not only on the drivers but also to society beyond the direct participants in traffic. There are a number of external costs associated with traffic congestion, including:

Increased travel times and delays for all drivers

Frustration that impacts productivity, quality of life, and overall well-being

High fuel consumption and emissions

Increased strain on infrastructure

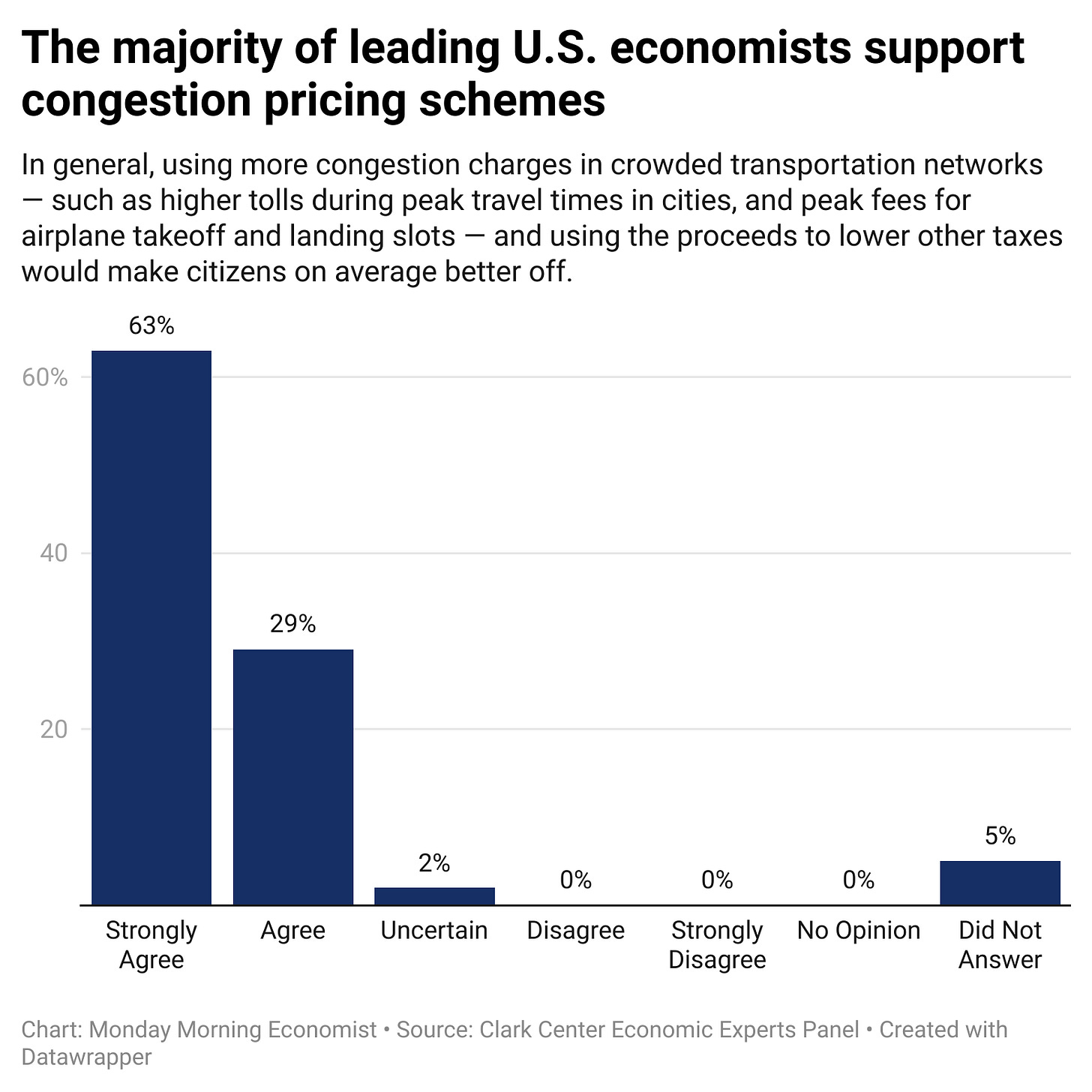

Thus, traffic congestion exemplifies the negative spillover effects that arise when individual decisions to use roads collectively result in a suboptimal outcome for society as a whole. Congestion pricing aims to reduce traffic congestion in busy urban areas by charging drivers a fee to enter designated zones that are prone to congestion. The pricing scheme incorporates several economic principles, and policymakers hope to achieve multiple objectives beyond reducing traffic volume and improving air quality, including generating revenue for mass transit improvements and addressing social justice concerns.

Instead of charging a single toll rate to drive among the core area of Manhattan, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) will take a more market-based approach by charging toll rates between $5 to $23 depending on the time of day. A market-based pricing approach ensures that toll rates reflect the demand for road usage during different times of day, discouraging peak-hour driving and incentivizing alternative transportation options. It aligns more closely with the concepts of supply and demand, where higher prices during popular time periods encourage drivers to seek alternatives or drive into the city during non-peak hours.

This approach isn’t new. There are a couple of major cities around the world that have implemented congestion pricing systems in an effort to address traffic congestion in the center of their cities. London’s congestion charge started back in 2003, and Stockholm’s system went into effect in 2007. Jonas Eliasson has a great Ted Talk on how congestion pricing has affected traffic in the Swedish capital city:

One of the major hurdles facing the policy’s implementation was its effect on low-income drivers and people who work in the transportation industry. To address these concerns, the MTA is implementing some price discrimination tactics to offset the equity concerns. Price discrimination occurs when people are charged different prices for the same product. Under the final proposal, drivers who earn less than $50,000 per year or who are enrolled in certain government assistance programs would get a 25% discount on tolls after making 10 trips per month through the tolling zone, for the first five years that the program is in effect.

Offering discounts to low-income drivers or to specific vehicle categories (like taxis and for-hire vehicles) acknowledges the trade-off between efficiency and equity. By reducing traffic congestion, the city hopes driving occurs more efficiently, but community advocates are concerned about the fairness of taxing people who need to be in the city and can’t afford the tolls. The discounts for taxis, for-hire vehicles, and low-income drivers acknowledge that congestion pricing might disproportionately impact certain groups. Offering discounts to these drivers helps mitigate the potential regressive effects of congestion pricing.

Lastly, the city’s plan is an interesting opportunity to look at revenue allocation. The revenue generated from congestion tolls is expected to be around $1 billion each year and will go toward financing improvements in the city’s mass transit system. By earmarking these funds for a specific purpose, policymakers can simultaneously demonstrate to residents where their tax dollars are going. Public transportation is often used as an example of a positive externality that has social benefits outweighing individual benefits. Investing the toll revenue in public transportation may improve the city’s overall support for the toll.

Economic principles provide a framework for evaluating the costs and benefits of policies, but it is essential to acknowledge that implementation challenges and differing viewpoints exist. Legal battles and public opposition are not uncommon when introducing significant policy changes. Some of the most outspoken critics of the plan are actually residents of New Jersey. Politicians are concerned that more trucks will drive through New Jersey to avoid the tolls in New York City and residents are nervous that their train commutes will be more crowded.

As the 30-day review period begins, stakeholders will have an opportunity to voice their opinions and potentially shape the final implementation of the congestion pricing scheme. The road ahead may still present obstacles, but it’s an exciting time to see how applications of key economic principles may aid in the city’s objectives of reducing congestion, funding mass transit, improving air quality, and promoting equity in New York City's transportation system.

Only 9% of NYC residents who work in Manhattan commute to work by car, while 39% of residents who work in the other boroughs choose car travel [NYC Planning Commission].

Among large metro areas, New York City has the longest average travel time to work, at 37.7 minutes, and the highest percentage of workers with commutes of at least 60 minutes, at 22.7% [US Census Bureau]

The average traffic speed in Midtown Manhattan is 4.7 miles per hour [Los Angeles Times]

Only around 3% of New Jersey commuters drive into Manhattan [NorthJersey.com]

I wonder why they're choosing not to fully exempt taxis from the charge. That would reduce likelihood of additional vehicles such as Ubers, and simply restore the yellow cab volume.

I was in New York City about a year ago and had a wild encounter with a woman who was going crazy over this proposed toll. How we met is a long story, so I'll cut to the chase. She had a really interesting thought, apparently shared by friends of hers, that this will kill business in the affected areas. Anyone who has to make an appointment for services like legal, medical, dentist, and possibly restaurants as well simply won't go if they have to pay the toll. Instead, business will move up town and rents near the 6oth street boundary will soar. Because most businesses pay rent, they can get out of their locations relatively easily making her hypothesis more believable. Of course, all policies, no matter how well intentioned, have side effects. I wonder if this will be one of them.