What do lobsters 🦞, whales 🐳, and elephants 🐘 have in common?

Two news stories popped up in my feed this week—both about animals adapting to environmental changes. At first glance, they had nothing in common. But from an economic perspective, they shared something crucial. Before we get into that, let’s run a quick thought experiment.

Imagine there’s an ATM in your neighborhood, but not just any ATM—this one is stocked with cash and doesn’t require a PIN or a card. Anyone who knows where it’s located can take out as much money as they want. Any leftover cash at the end of the day earns interest, meaning there could be even more to withdraw tomorrow.

How long would it take before you paid this ATM a visit? And how much would you take on your first trip?

If you were the only one who knew about it, you’d probably be careful with how much you take out. You might withdraw a little, but you’d also let it grow—maybe just skimming off the interest each day while keeping the balance high. You might even add money to the ATM, knowing it would pay off over time. After all, when something belongs to us, we tend to take better care of it.

But what if the whole neighborhood found out about your ATM? Suddenly, your carefully managed cash stash turns into a free-for-all. Neighbors drop by in the morning for some quick cash. Strangers take their cut. And now you’re faced with a dilemma: wait too long, and there might be nothing left. The incentive shifts from long-term preservation to grabbing as much as possible before it’s gone. No matter how high the interest rate, the balance will never grow—because there won’t be any money left.

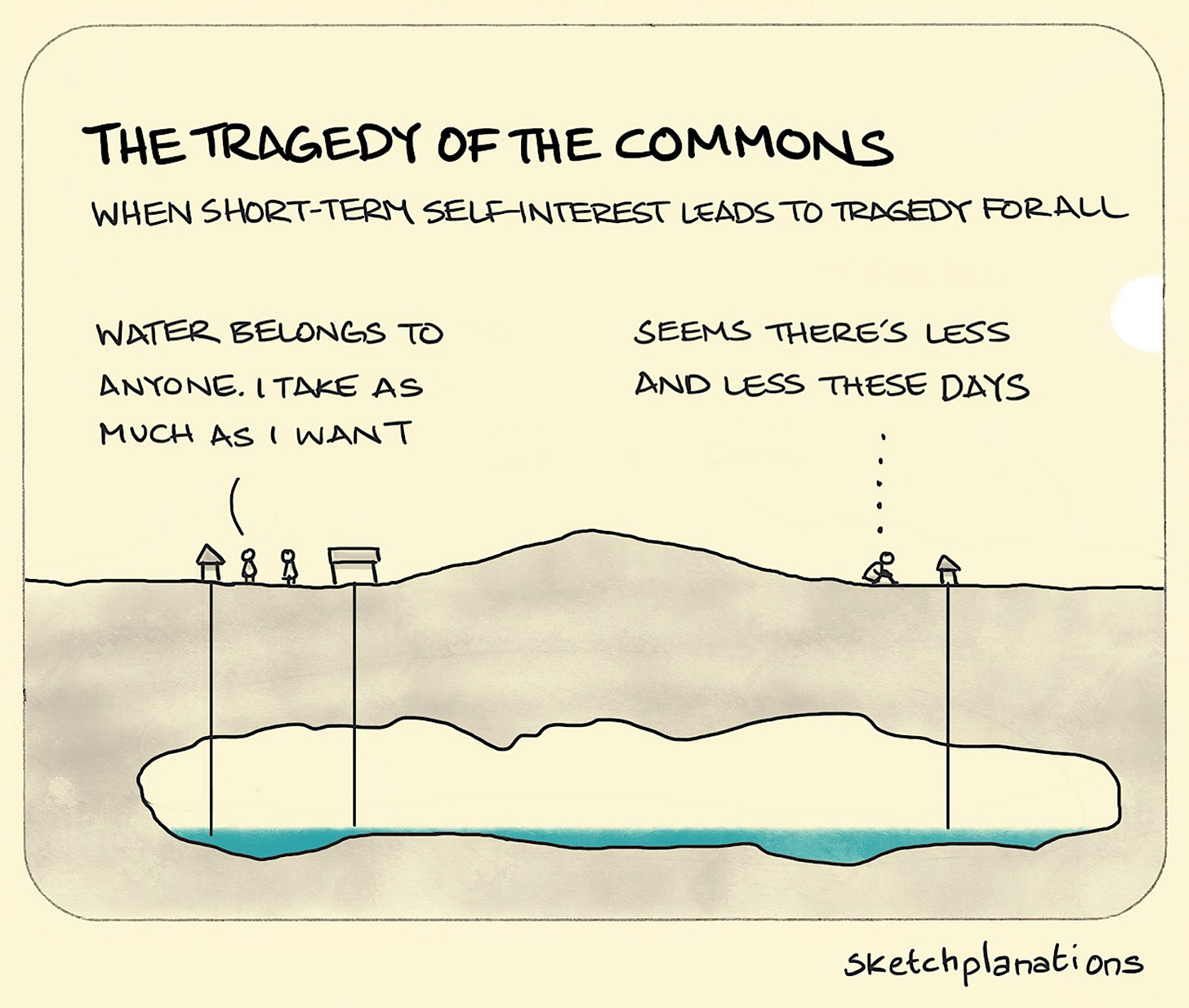

Our hypothetical scenario isn’t just a neighborhood run amok—it’s a modern-day version of the tragedy of the commons, an economic dilemma that plagues resources with two key characteristics.

First, there’s rivalry. If one person’s use of a resource directly reduces how much is left for everyone else, you’ve got a problem. Your neighbor clearing out the ATM before you get there is a perfect example—once the money’s gone, it’s gone. A fishery facing overfishing, an overgrazed pasture, or a congested freeway during rush hour? Same issue. One person’s consumption leaves less (or nothing) for others.

But rivalry alone doesn’t cause a tragedy. The real problem? Lack of ownership. In our ATM scenario, there are no clear property rights—no rules governing who can access the cash or how much they can take. That creates a perverse incentive: grab what you can before someone else does. When you were the only one who knew about the ATM, you had every reason to be careful. You saw the money as yours and treated it like a long-term investment. But once access became free-for-all, patience and conservation went out the window.

This is what separates common resources from private goods. You could, in theory, walk into Old Navy and buy every pair of jeans in stock, leaving none for other shoppers. But you can’t just take them without paying. That’s the crucial difference—private ownership gives businesses control over how resources are allocated, preventing depletion.

Of course, simply privatizing everything isn’t always a perfect solution. Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics, spent her career studying how societies manage common resources without falling into tragedy. Her research showed that well-designed community rules—rather than just government mandates or private ownership—can help preserve shared resources. In 2009, she won the Nobel for showing that the tragedy of the commons isn’t inevitable.

Lobster Wars and Warmer Waters

Forget the hypothetical ATM—let’s talk about real-world resources that generate serious economic value: lobsters, whales, and elephants. Each has been threatened by overexploitation, and without intervention, each faces the risk of depletion or extinction. Even where governments have stepped in, illegal activity and environmental shifts continue to test conservation efforts.

Take lobsters. In the Gulf of Maine, lobster populations are thriving, but just south, in Southern New England, they’re dangerously low. Why? One big reason: warming waters. Meanwhile, off the coast of Africa, poachers have driven elephant populations to critically low levels in pursuit of ivory. And though commercial whaling is largely a thing of the past, the North Atlantic right whale still struggles to recover from centuries of overhunting.

Each of these species has experienced its own version of the tragedy of the commons, but now, climate change is adding a new layer of complexity. Policies that once worked may no longer be enough.

Maine has some of the richest fishing grounds in the world, and lobster is its crown jewel. But that’s only because of strict government regulations designed to prevent overfishing. Without them, the market would quickly deplete the resource, just as it has in Southern New England.

The problem? The ocean isn’t staying the same. Over the past few decades, rising water temperatures have pushed lobster populations northward, away from their traditional habitats. The documentary Lobster War details the tensions this has created, particularly as fishermen from different regions—and even different countries—compete for access to this high-value resource.

For now, Maine’s lobster population is considered “appropriately stocked.” But early warning signs are appearing: the size of lobster and soft-shell crab catches has declined in recent years. If Maine’s waters continue warming, its lobster population may follow the same downward trajectory as New England’s. And as the resource becomes scarcer, incentives to overfish will only grow.

But lobsters aren’t the only ones moving north.

Whales vs. Fishing Vessels

The North Atlantic right whale isn’t being hunted anymore, but that doesn’t mean it’s safe. Its primary food source has been disappearing due to warming waters, forcing the whales to migrate farther north in search of sustenance. And that’s putting them in increasing danger—not from harpoons, but from fishing vessels.

Lobster fishing may be sustainable for now, but it comes with external costs. As boats head out to sea, they unintentionally threaten the already endangered right whale. In recent years, two-thirds of known whale deaths have been caused by fishing-related incidents—either from ship strikes or entanglement in nets.

Here’s where the economic trade-off gets complicated. Maine’s lobster industry generates billions of dollars and supports thousands of jobs. Right whale tourism, on the other hand, also brings in revenue but relies on the whales surviving. The more fishing vessels spend time at sea—especially as they chase dwindling lobster populations—the greater the risk to the whales.

It’s a classic externality problem: the economic activity that benefits one group (lobster fishermen) imposes costs on another (whale conservationists and tourism operators). Balancing these competing interests will be a growing challenge as environmental conditions continue to change.

The Evolution of an Anti-Poaching Defense

Now let’s shift from the sea to the savanna. Decades of elephant poaching in Africa, driven by demand for ivory, have left some populations in crisis. Even with strict government protections, illegal poaching remains a persistent threat. But in Mozambique, something remarkable has happened: evolution may be fighting back.

Some elephants are born with a rare genetic trait that leaves them tuskless. Historically, this was an uncommon occurrence. But because poachers exclusively targeted elephants with tusks, those without them had a survival advantage. Over time, this trait became far more common. It’s a real-world case of selective pressure—poaching altered the genetic landscape of the elephant population.

At first glance, this might seem like a win: fewer tusked elephants means less incentive for poachers. But there’s a catch. In males, this tuskless trait is linked to lower reproductive success, which could ultimately reduce birth rates and weaken population recovery in the long run.

It’s a stark example of how human economic behavior—specifically, the pursuit of valuable resources—can shape the very evolution of a species. And it raises an important question: even if elephants become less valuable to poachers, will their populations still decline due to these unintended genetic consequences?

Final Thoughts

The tragedy of the commons isn’t a static problem—it shifts with the environment. Regulations that once worked may need to be rethought as species migrate, adapt, or face new threats.

Maine’s lobster industry is currently well-managed, but warming waters could push the fishery past its tipping point.

Right whales, no longer at risk from whaling, now face a different threat: the very vessels that sustain Maine’s lobster economy.

Elephants may be evolving a defense against poachers, but the long-term genetic effects could introduce new challenges.

Elinor Ostrom’s research showed that commons problems can be solved—not just through government mandates, but through cooperative management and well-designed incentives. The challenge now is adapting conservation efforts in real time to account for climate shifts, economic pressures, and even the unexpected consequences of evolution itself.

Over the past 30 years, the Gulf of Maine has warmed faster than 99% of the world’s ocean [The Economist]

An estimated $668 million worth of lobster was caught in the United States in 2019 [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]

There are only an estimated 368 living North Atlantic right whales left in the world [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]

Around 90% of Mozambique’s elephant population was slaughtered by poachers between 1977 to 1992 [The Telegraph]

Week #42 is done and I’ve checked in a total of 61 books so far this year. This past week I finished up Four Hundred Souls, which looks at 400 years of different people and events that have influenced the journey of African Americans in the United States. The centuries are broken up into 5-year intervals and each has a different author.

If you’re looking for a good book related to this week’s topic, I would highly recommend Endangered Economies by Geoffrey Heal. The book looks at issues in natural resource economics like pollution, climate change, and common resource problems. I used this book in my Natural Resource Economics course in 2020 and loved it.