The Million Dollar Decision

It’s an exciting time of the year for many students around the country. High school seniors are narrowing down which university they want to attend in the Fall. Some will go straight to their dream school, while others may need to start at a community college. While high school seniors make that decision, college seniors are getting ready for commencement. Many of them will likely be looking back to figure out if it was all worth it. Thanks to a new report from the Pew Research Center, college still looks like a worthwhile investment.

The cost of a college degree often receives most of our attention and focus, but there rarely seems to be as much focus on the variation in benefits from a college degree. There is variation in the cost of attending school based on a number of considerations, but those costs tend to be more easily observable. The benefits of a degree are much less easy to predict and can vary in a number of different ways. In essence, young adults are asked to pay a substantial amount of money up front and hope for a sizable return in the future.

Some students are able to finance their entire college experience on their own, but many others rely on loans. Regardless of the payment method, students and their families invest a lot of money and time over a handful of years in the hopes of getting a better job later in life. Gary Becker was one of the key economists who conceptualized this investment decision, but the importance of this insight is often taken for granted today. It’s a powerful way of thinking about the decision and its implications:

So, is college worth it? The direct costs, while substantial, are posted on most university websites and don’t even include reductions for merit and need. The indirect costs are a little harder to calculate but are relatively low compared to later in life. The benefits are the hardest part of the calculation because so much of the data is reported in the aggregate. There are great resources online for a high school student deciding which major to pick if they care about lifetime earnings or for graduating college seniors who want to see how their job market compares to others.

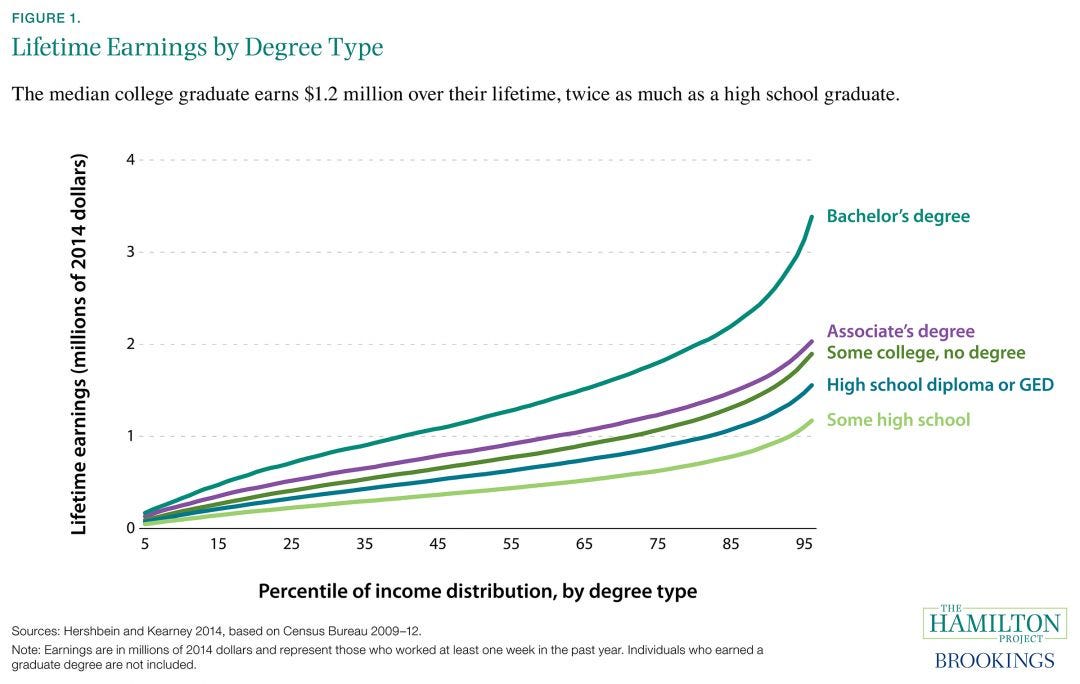

Typically, the median college graduate will earn about $1 million more in their lifetime compared to the median high school graduate. And now we get to our first issue of measuring the benefits of a college degree. There is a lot of noise around that particular value. Just because the median is a $1 million dollar surplus doesn’t mean that every college graduate will see those same benefits. There are some great paying jobs that don’t require a college degree and there are some college degrees that often lead to relatively low-paying job prospects. The starting pay for new Walmart truck drivers is between $95,000 and $110,000; no college degree is required!

The most obvious difference in salaries will depend on which industry and occupation a student enters after graduation, and a lot of that will be influenced by which major they select(ed). There is a lot of variation among college majors. Some jobs have very clear paths (accounting majors tend to become accountants), but they’re not always so direct. It turns out that the most common job for recent economics majors is also accounting. The #5 occupation for recent economics graduations (postsecondary teacher) pays about less than half the occupations ranked #1 through #4.

Another concern with this measure rests on when college graduates will see those benefits. The unemployment rate decreases with additional levels of education, but that doesn’t mean all employment is created equally. Recent college graduates tend to be underemployed relative to all college graduates. About 40% of recent graduates are working jobs that don’t require a degree. This usually is related to how long it takes to find an entry-level job associated with the degree a student earns. That value has been fairly constant over time but tends to increase after recessions. Here’s data from the New York Federal Reserve comparing underemployment rates for recent graduates and all college graduates. They also have interesting data on the underemployment rate by major (sorry Criminal Justice majors).

The underemployment measure actually helps highlight another one of the issues with measuring the benefits of a degree. Almost 3/4ths of Criminal Justice majors are underemployed because many of them go into law enforcement, which does not require a college degree. Yet, this is the field that many of them want to be in. Earnings data doesn’t capture preferences or interest in a particular job. College graduates tend to have great job security, healthier behaviors, and more civic engagement as well. These benefits have value but also aren’t easily captured by the data. These are also outcomes that are particularly valuable to society as a whole, which are used to justify government funding and support for higher education.

A final issue of the college premium is related to how much of those benefits are even caused by earning a degree instead of just being correlated with educational attainment. Since students aren’t randomly assigned to go to college or go to work when they graduate high school, some of that college income premium may represent the self-selection bias. Perhaps there is some innate characteristic about college graduates that lead them to finish a degree that would also make them successful at work. Alice Rivlin, who has served as the Vice-Chair of the Federal Reserve and the founding director of the Congressional Budget Office, remarked that:

The only reason that education is correlated with income is that the combination of ability, motivation, and personal habits that it takes to succeed in education happens to be the same combination that it takes to be a productive worker.

And that issue brings us to one final consideration on the impact of higher education, which is whether students are learning anything at all. Perhaps the college experience mostly just sorts people into different groups: those who never go because they don’t want to, those who go but don’t finish, and those that can survive 4-6 years and finish all the requirements. Perhaps the diploma doesn’t certify much was learned, but it is proof of completion. College graduates have physical evidence that they can follow directions and turn their work in on time. Tyler Coen and Alex Tabarrok have a great Econ Duel on this topic:

I know I haven’t answered the question, and that’s on purpose. The answer really is “it depends.” For some, a college experience goes beyond what’s learned in the classroom and involves a host of experiences that will last a lifetime. For others, it’s a gateway to a career they’ve been passionate about since they were young. While the cost of a degree receives the most attention, it’s always important to highlight the benefits of a degree beyond the expected salary.

The average tuition and fees for first-time, full-time undergraduate students enrolled at public 4-year institutions was $9,400 per year in 2019 [National Center for Education Statistics]

Only 62% of students who start a degree or certificate program finish their program within six years [National Student Clearinghouse]

As of 2021, 37.9% of all adults over the age of 25 held at least a bachelor’s degree [US Census Bureau]

About a fifth (19%) of the roughly 2 million bachelor’s degrees conferred in 2019-20 were in business [National Center for Education Statistics]

As someone sending kids to college in the fall for the first time, this is an incredibly relevant topic. Two things I'd like to add. First, if you are going to a private college be prepared to pay way, way more than the dollar figure you quoted. I wonder if the rate of return on the private liberal arts education is anywhere close to that of the state run education. Second, Bryan Caplan has a fantastic book about the educational machine called "The Case Against Education". Being as Bryan makes a living as an academic economist, it may seem odd that he is shooting at the golden goose, but that may make his arguments that much more credible.