A Costlier Cup of Coffee Coming Soon ☕️

A trifecta of forces is causing coffee bean prices to reach the highest they’ve been in nearly a decade. The vast majority of the coffee consumed in the US and Europe is grown overseas, which means the supply chain issues affecting all of the other things we buy are also impacting the delivery of coffee beans to your local roasters. As countries have started opening up over the past year, coffee joins the list of other items seeing increased demand. Lastly, weather disruptions across coffee-growing regions have reduced the supply of coffee on the market. All three have created a less-than-ideal situation where your cup of coffee may be more expensive in the near future.

Coffee beans (both arabica and robusta) are traded around the world on commodity markets and have posted the largest price increase of any commodity this year. Food prices, in general, have also hit a 10-year high, based on data from the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization, but haven’t grown nearly as much as coffee prices have grown. Arabica beans account for about 75% of the world’s production and are mostly cultivated in Brazil, which makes up about 40% of the world’s total supply. Coffee producers estimated that almost half a million acres of coffee crops were hit by the frost in Brazil, the worst the country has seen in 27 years. A local coffee grower in Brazil told Reuters:

On this property, we have lost 80% of the coffee crops. In this region, I think 30 to 40% of the coffee plants have been damaged.

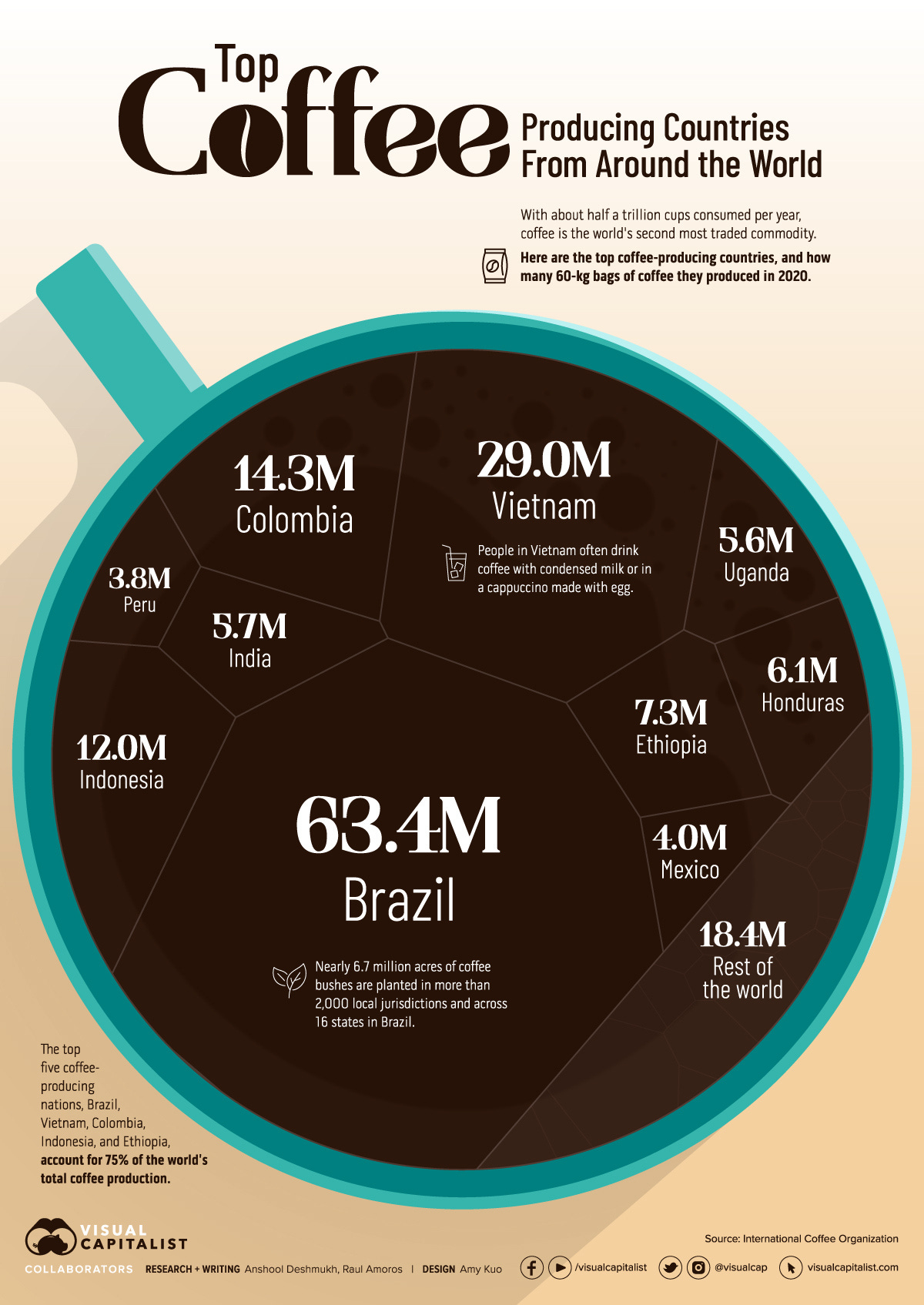

Robusta beans make up the other 25% of the coffee beans market and are mostly produced in Vietnam and Indonesia. The robusta bean is popular across Europe and espresso coffee while the arabica bean is more popular in the United States. Coffee is one of the world’s most traded commodities. The top five countries (Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, and Ethiopia) make up about 75% of the world’s exports:

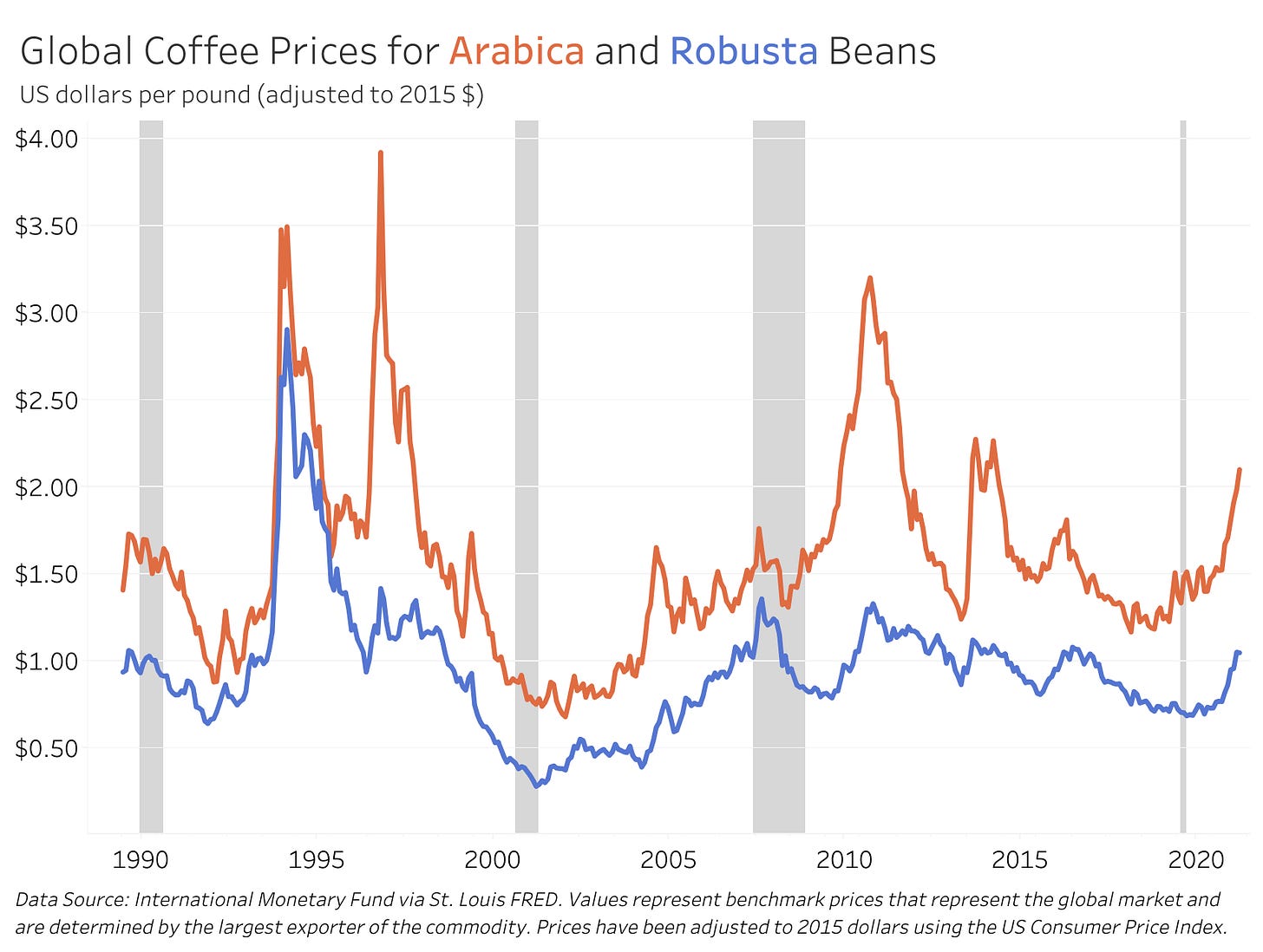

Before the pandemic started, coffee prices were at a decade-long low point, which is why this particular swing in coffee prices has been so dramatic. While the price of coffee beans has risen very quickly since the start of the pandemic, they’re still well below various high points that have occurred during the past 30 years. Many of the previous peaks were also associated with extreme weather impacting major growing regions.

Below are global coffee benchmark prices reported by the International Monetary Fund dating back to 1990. These prices are determined by the largest exporter and are intended to be indicative of the global price of the commodity being reported. The data from the IMF was reported in nominal terms (prices for that particular month in time), but I’ve adjusted them to real terms to account for inflation by using the U.S.’s consumer price index for the associated month in time. The values below for arabica and robusta beans have been adjusted to the 2015 prices in US dollars.

While the IMF data are reported for two different types of beans, there are more pricing considerations to the beans that coffee roasters actually decide to purchase. This differentiation can lead to a wide range of prices based on how the beans are sourced or the quality of each particular bag of beans. While coffee is traded as a commodity, there can actually be a lot of differences between the types of beans you buy.

Some roasters pay significantly higher prices for their beans to ensure that the beans are grown in an environmentally and socially conscious way (fair trade) while other roasters purchase beans directly from the growers (direct trade) to ensure that more money goes back to the coffee growers rather than an intermediary. It’s the same push you’ve likely seen in the chocolate industry as well. Another consideration for coffee roasters is how the coffee beans are graded, with higher grades often commanding significantly higher prices.

While the beans themselves are getting more expensive for importers and the roasters, it may take a while for the price increases to trickle down to the cup of coffee at your local coffee shop or diner. Larger companies (like Starbucks) have already announced their prices will likely remain stable for the next year since they purchase coffee beans 12 to 18 months in advance. Another issue is that the price changes are primarily affecting one point along the supply chain: the importers of beans. If coffee customers are sensitive to price changes for their coffee, the importers may not be able to pass along much of the price increase down the supply chain. The bigger issue for most coffee roasters right now isn’t how much the coffee beans cost, but rather when the coffee beans will actually arrive.

The November 2021 benchmark price for a pound of arabica beans was $2.63 and $1.27 for a pound of robusta beans [International Monetary Fund]

Coffee is measured in 60 kg bags, and a total of 169.6 million bags were produced worldwide in 2020 [International Coffee Organization]

From June 2020 to July 2021, Brazil produced 69.6 million bags of coffee beans [US Department of Agriculture]

The average urban retail price of ground regular caffeine content coffee sold in a can or plastic containers in the U.S. was $4.81 per pound [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

The United States, the world’s largest importer of coffee, imported $5.53 billion worth of coffee in 2019 [Observatory of Economic Complexity]

Now do iced tea! But for real, it's interesting to see everything affected by this pandemic and global supply chain issues. Some great supply/demand questions could be written on this post.

Some of what ended up happening, looking back now...

With some of the previously negotiated contracts, importers had problems with producers reneging on the deals.

As prices rose, producers were unwilling to supply at the previous low prices.

And when this happened with major producers like Colombia, it left quite a mess.

Because the supply curve shifted once again with producers only willing to supply at the higher price.

The Colombia situation:

https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/exclusive-major-coffee-buyers-face-losses-colombia-farmers-fail-deliver-2021-10-11/