The Nuts & Bolts of the Airplane Oligopoly

The market for commercial aviation would be characterized as an oligopoly, dominated by just two titans: Boeing from the United States and Airbus from Europe.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 3,800 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

In the high-flying world of commercial aviation, a new storm has emerged from an unlikely place: the bolts of Boeing’s aircraft doors. On January 6th, the FAA called to ground flights involving certain Boeing models after a panel blew out in the middle of an Alaska Airlines flight the day before. One later, the National Transportation Safety Board announced they believed the bolts on the Boeing jetliner were missing before the plane ever took off. The events haven’t just been a blow to Boeing’s share prices; they have rattled airlines and passengers alike, sparking concerns over safety in the skies.

The market for commercial aviation would be characterized as an oligopoly, dominated by just two titans: Boeing from the United States and Airbus from Europe. This level of concentration creates a situation where the concept of interdependence is of critical importance; the actions of one company significantly impact the other. Strategic decisions by Boeing, for example, regarding pricing, innovation, or capacity expansion, elicit a direct response from Airbus, and vice versa.

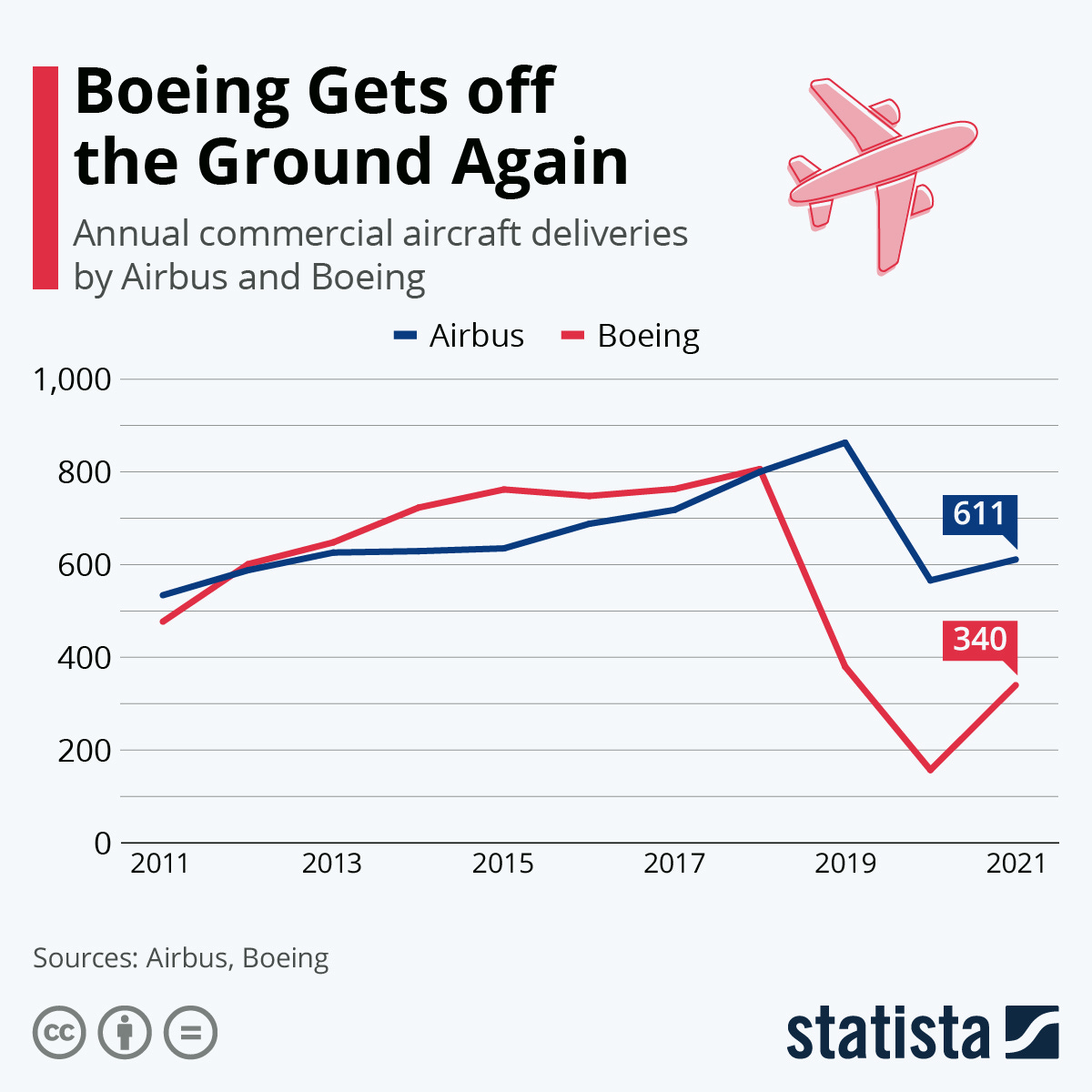

But understanding oligopolies isn’t just about knowing your rival’s next move. Boeing has been around since 1916, but there’s mounting pressure from airlines and customers to switch to Airbus, a formidable foe that entered the fray in 1969. They’ve steadily climbed to the top and become the world’s largest planemaker in 2019. But let’s be clear, Airbus’s rise to the top wasn’t a smooth flight—controversies and turbulence were part of the journey.

When One (Airplane) Door Opens…

Let’s start with Boeing’s recent troubles. The issue with door bolts might seem minor in the grand scheme of an entire plane, but it has caused people to question Boeing’s quality control and oversight. While there were no serious injuries reported on the flight, several passengers claimed they experienced “havoc, fear, trauma, [and] severe and extreme distress” from the incident, according to a pending lawsuit against Alaska Airlines and Boeing.

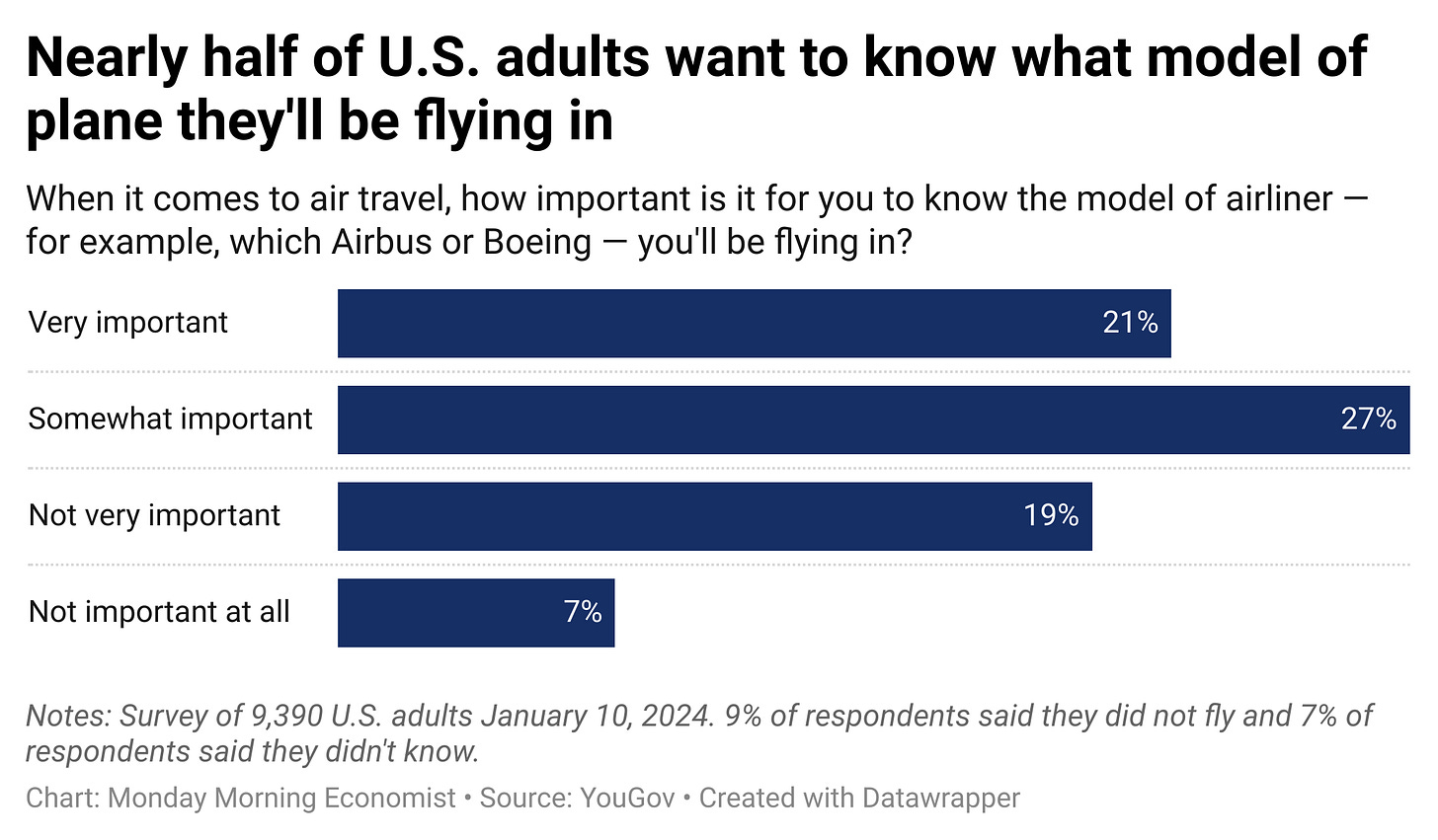

Boeing lost 19% of its market capitalization within the first month, but the long-term costs may be more significant as a tarnished reputation could result in airlines leaning more towards Airbus when it comes to future orders. Airbus benefited a few years ago when Boeing’s 737 Max planes were grounded after tragic incidents in Indonesia and Ethiopia. Boeing’s latest challenge might further solidify its lead, despite the industry being fraught with other controversies.

Gaining market share in oligopolistic markets acts as a barometer of a firm’s competitive strength. Whether firms engage in Bertrand competition by undercutting prices, in Cournot competition by optimizing production quantities, or in Stackelberg competition by leading the market, the underlying goal remains the same: to increase market share. While it’s easy to focus on selling more products, the pursuit is about enhancing the company’s influence over market conditions, improving its ability to dictate terms, and securing a safer position against economic shifts and disruptions.

International Relations Are Turbulent

Behind the scenes of this aviation drama lies a complex web of international trade relations. Boeing and Airbus are symbolic of the American and European industrial might. They’re constantly embroiled in a duel that stretches into international diplomacy, trade policy, and the shadowy world of subsidies and tariffs.

Both aviation giants have enjoyed significant support from their governments, through subsidies, tax breaks, and funding for military and research contracts. Boeing’s annual report to the Securities & Exchange Commission doesn’t shy away from pointing out the competitive edge this gives Airbus, particularly through "launch aid" that reduces the costs and risks associated with developing new planes:

We face aggressive international competitors who are intent on increasing their market share. They offer competitive products and have access to most of the same customers and suppliers. With government support, Airbus has historically invested heavily to create a family of products to compete with ours.

This government-backed financial support has been a bone of contention, leading to a series of legal battles and World Trade Organization rulings aimed at mediating these disputes. Yet, these rulings often intensify the tension between the U.S. and the EU, showing just how challenging it is to maintain fair competition on a global stage. The battle for the skies isn’t just about who builds the better jet but also who gets the bigger boost from their government.

The constant feud between Boeing and Airbus cuts to the core of oligopolistic competition. The financial support gives each a leg up, allowing them to lower the cost of production. This, in turn, allows them to offer their aircraft at lower prices to airlines or invest more heavily in research and development, innovation, and market expansion strategies. That doesn’t sound like a bad thing, right?

While it makes sense for nations to back their champions, this strategy is contentious. Government intervention has altered the competitive landscape of what’s intended to be a free market. Each side cries foul because they don’t believe the other is a better competition, but rather that the other is successful by playing politics. So as Boeing faces this latest challenge, the stakes are high. How they handle the door bolt issue could either swiftly restore their market share and reputation or give Airbus an even greater edge.

There are an estimated 477,570 people employed in the Aerospace Product and Parts Manufacturing industry in the United States [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

Over the past 15 years, Airbus has delivered just over 1,800 twin-aisle jets and Boeing has delivered almost 2,600, giving it about 58% market share [Baron’s]

In 2013, a Boeing 787 with a list price of $225 million was selling at an average price of $116 million, a 48% discount [Forbes]

As of December 31, 2023, Boeing employed approximately 171,000 workers, with 14% of its workforce located outside of the U.S. [Boeing]

Following WTO decisions, both the US and the EU imposed punitive tariffs on each other's exports, totaling over $3.3 billion in duties [European Commission]

Given the distorted market of plane construction, I wonder if both the US and EU should subsidize a new competititor - at least maybe make a plane builder of a different model of plane (smaller than an A320/B737) that would be completely independent of any of the big players.