Why Some of Us Never Switched Back to Regular Eggs

When $2 eggs jump to $5, suddenly $7 eggs don’t seem so crazy. Economics has a name for that.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

For the majority of my life, eggs were eggs. I bought the cheapest ones I could find—usually in a white styrofoam carton, usually near the milk. Then, during one of the recent egg price spikes (thanks, bird flu), I picked up a carton of pasture-raised blue-shelled eggs instead. I wasn’t trying to make a statement. I just needed eggs, and the price gap didn’t seem as steep that day.

I don’t eat a lot of eggs—maybe a dozen every few weeks—so the extra few dollars didn’t feel like much. What surprised me wasn’t that I bought the blue eggs that day. It’s that I never stopped buying them when I needed eggs again.

Even now, with the price of regular old white eggs falling fast, I still reach for the fancy ones. Not because I made some ethical decisions in the middle of Kroger—but because I like them. The yolks are richer. The shells are prettier. And maybe, just maybe, the chickens had a better life.

Turns out I’m not the only one.

What Happened to Egg Prices?

You probably don’t need another explainer on bird flu, but here’s the short version: starting in 2022, repeated detections of avian influenza led to the culling of millions of egg-laying hens across the U.S. Under current policy, a single case of bird flu requires the entire flock to be euthanized, even if only one bird tests positive. That policy—not the virus alone—disrupted the supply chain and drove up prices for conventional eggs that you would usually find in a styrofoam carton at the grocery store.

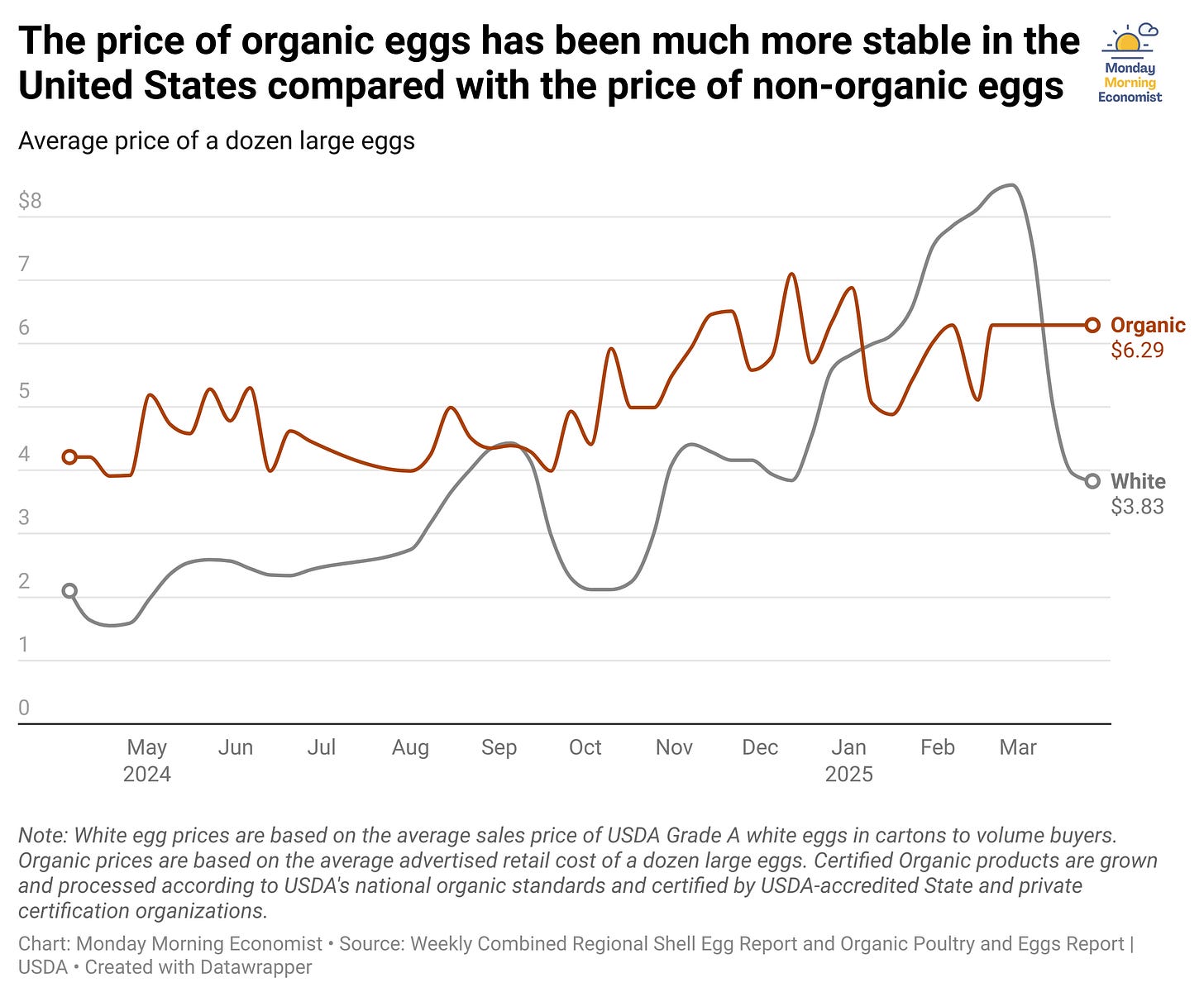

At its peak last year, a dozen Grade A Large eggs that were once priced around $2 were selling for $5 or more. They recently got as high as $8.50 for a dozen eggs. Some grocers responded with purchase limits. Others simply ran out.

But something odd happened on the high end of the egg market. Prices for organic and pasture-raised eggs barely moved. Pete & Gerry’s, one of the bigger specialty brands, said its retail price stayed near $6.99 the whole time. Their supply chains weren’t hit as hard, and their pricing isn’t as tightly tied to the commodity market.

So while the price of regular eggs soared, the price of premium eggs stood still. For a brief moment this year, the organic, pasture-raised eggs were the cheaper option! Even when they weren’t, the relative price gap had narrowed so much that it changed how some people thought about which eggs were “worth it.”

Conventional egg prices have dropped sharply overt the past few weeks as bird flu outbreaks eased up, according to the USDA. But a funny thing happened along the way: some shoppers who upgraded to fancy eggs never looked back.

A Lesson in Relative Prices

Economists Armen Alchian and William Allen weren’t trying to change the way we buy eggs. But in the 1960s, they described a pricing phenomenon that helps explain what’s been happening back near the dairy aisle. It’s now known as the Alchian-Allen Effect.

Here’s the basic idea: when a fixed cost is added to two similar products—like a tax, a shipping fee, or even a supply shock—it can make the higher-quality item look like a better deal, even if its price doesn’t change.

Let’s say regular eggs cost $2 and pasture-raised eggs cost $5. That’s roughly what they cost last year. That $3 difference is enough to make most shoppers stick with the cheaper option. After all, the pasture-raised eggs were 2.5 times more expensive than the cheap eggs!

But when bird flu hit the poultry industry, prices started going up. If both products increased by $2 so that regular eggs cost $4 and pasture-raised eggs cost $7, the relative price falls. The overall gap is the same, but now pasture-raised eggs are only 1.75 times as expensive. Suddenly, the price gap doesn’t seem as big of a deal as before. For a couple of extra dollars, you get eggs that many people think taste better, look better, or come from a more humane farm.

That small change in relative price can have a big impact on behavior. Specialty egg producers reported a noticeable rise in demand during the price spike. And even now—months after prices for conventional eggs have started falling—many of those shoppers are still buying the good stuff.

Once people get used to a certain taste or quality, it can be hard to go back. That’s especially true for items we don’t buy in large quantities. Spending an extra few dollars on cereal every week might give me pause. But a few extra dollars for eggs I buy every other week? That’s easier to justify. And if the yolks are richer, and the shells a little sturdier—it starts to feel less like a splurge and more like a small upgrade I’m happy to stick with.

Final Thoughts

Funny enough, I was talking about this same idea over breakfast recently—though not about eggs. A friend of mine recently moved from a small college town to a major city and was venting about drink prices in the city. He refused to pay $9 for a Yuengling at a downtown bar when, for just a few dollars more, he could get a local craft beer he knew he would enjoy more.

That’s the Alchian-Allen Effect again. When fixed costs—like higher rent, delivery fees, or even just geography—push up the price of everything, the premium option doesn’t seem so out of reach. As coffee prices increased because of droughts, that bag of premium roast suddenly felt like a worthwhile upgrade.

The broader point is this: when prices rise across the board, we don’t just rethink what we’re spending—we rethink what we’re spending for. It’s not just about how much something costs. It’s about what else you could get for nearly the same price. And sometimes, once we’ve tried the better option, we don’t go back.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 6,800 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

The U.S. egg-hen flock is down about 50 million birds, or 15%, from its usual level [American Egg Board via NBC News]

Fewer than 150 commercial egg farms with flocks of at least 75,000 now house over 95% of egg-laying hens [United Egg Producers]

Approximately 2.08 million birds were culled due to bird flu in March compared to 12.67 million in February and 23.19 million in January [USDA]

Free-range means that the eggs come from hens that have some sort of access to the outdoors, but it doesn’t mean that the hens actually go outdoors [Eater]

One more thing, unrelated to the economics of eggs. The avian influenza outbreak did not kill millions of laying hens. It’s the government’s mandate that all hens be euthanized if a laboratory detect is positive.

Once you've raised hens you will never buy the cheap eggs again.