Economic Concepts on the Ballot

A number of states and localities passed measures that have significant economic implications. These policies include applications of human capital investment, public choice, and price controls.

Last week featured a number of marquee congressional and gubernatorial races across the United States, but a number of initiatives were also considered across states. Some measures seemed a bit goofy, like Tennessee ratifying its state constitution to (finally) outlaw slavery, but others had clear economic implications. A number of initiatives focused on tax-related issues (like increasing sales taxes in Arizona or income taxes in California), but a few of them were unique in the sense that they focused on interesting economic concepts.

Instead of taking a deep dive into one of those initiatives, I have picked three topics to cover. Each section provides a brief summary of the measure and the program but includes a lot of links so that you can learn more about the measures you’re most interested in learning more about. The three topics that were approved by voters last week include:

Because of how much content is included in this week’s newsletter, your email provider may cut off the bottom half of the post. To ensure that you’re seeing the whole story, read this post on Monday Morning Economist online or on the new Substack app:

School Lunches & Human Capital

Colorado voters approved Proposition FF, which reduces the amount of state income taxes that could be deducted for individuals earning more than $300,000 per year. That additional tax revenue will be used to create (and support) the Healthy School Meals for All program. The program provides universal school lunches for public school students and raises wages for cafeteria workers. State officials estimated that changing the deduction policy would increase state revenue by $100.7 million per year.

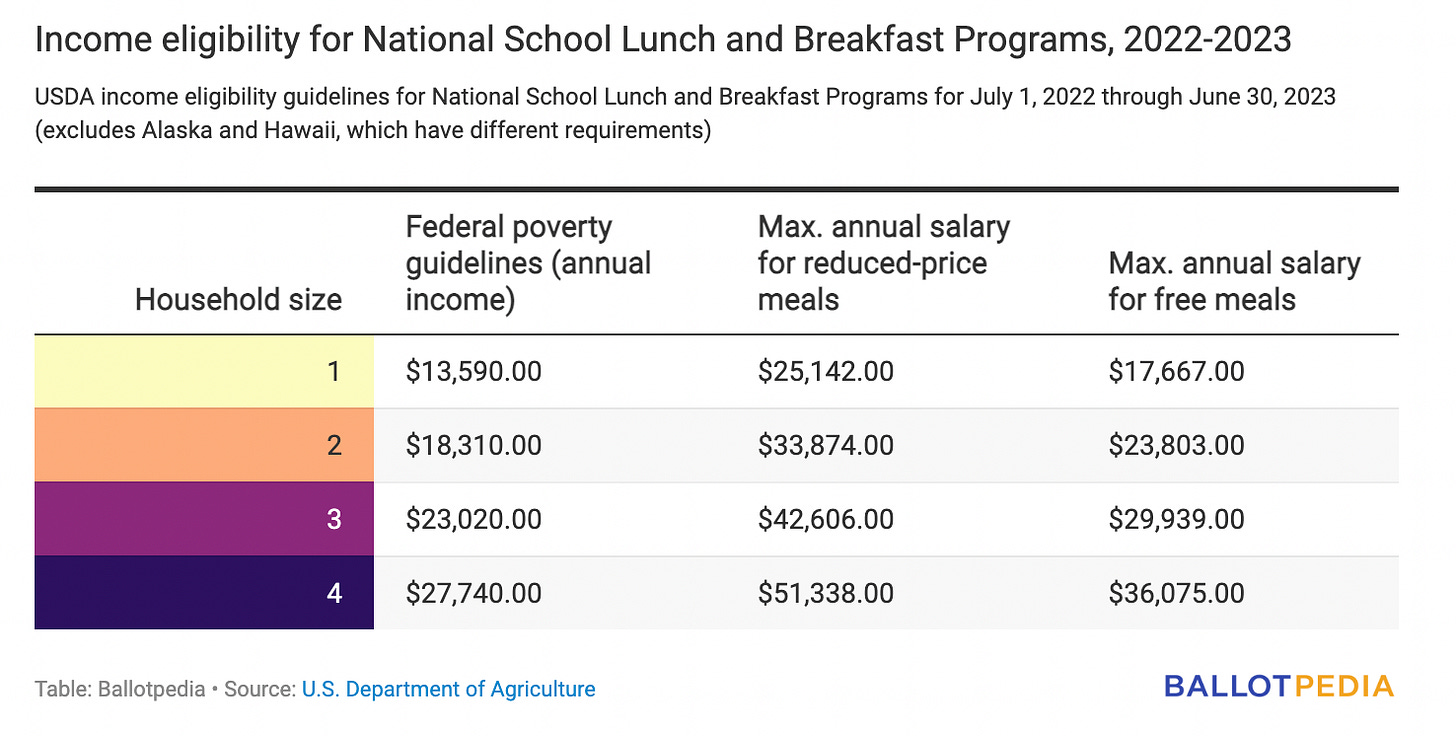

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) was established in 1946 and reimburses participating schools that provide free or reduced-priced meals to eligible students based on their household’s annual income level. During the initial two years of the pandemic, the federal government issued waivers to the program so that all students, regardless of financial status, could eat school meals for free. Those waivers, however, expired over the summer. This proposition replicated those federal waivers so that the state covered the cost. Colorado students will now have access to breakfast and lunch each school day, regardless of their family’s financial status.

Funding education initiatives is a great example of investing in human capital, but it’s one of many ways that policymakers can improve the quality of the future workforce. These programs are seen as an investment because they require upfront costs that take several years (or decades) before seeing the returns. Because of this structure, it can be difficult for individuals to make those same investments on their own.

"Whenever I am asked what policies and initiatives could do the most to spur economic growth and raise living standards, improving education is at the top of my list."

—Janet Yellen | Chair of the Federal Reserve (Source)

Researchers have found that healthier meals and increased access to the National School Lunch Program result in improved end-of-year test scores. Improved access has also been linked with improved lifetime earnings and reduced chronic health issues later in life. From a social investment standpoint, researchers have estimated that school lunch programs around the country provide nearly $40 billion in health and economic benefits while costing only $18.7 billion per year to run.

Ranked Choice Voting and the Median Voter Theorem

Nevada has taken the first step toward using ranked-choice voting across the state for major elections. In order to amend its state constitution, however, Nevada voters must approve initiatives in two even-numbered election years. The same initiative will come up again in the 2024 election, and if approved again, will establish ranked-choice voting in general elections for congressional, gubernatorial, state executive official, and state legislative elections. The adoption of ranked-choice voting varies tremendously across (and within) states:

A ranked-choice voting system asks voters to rank candidates on their ballots rather than selecting a single candidate they prefer. If a single candidate wins a majority of first-place votes, they are declared the winner. Ranked-choice voting comes into play only when the top candidate only wins a plurality of votes instead of the majority of votes. Some states (and the presidential election allow candidates to take office based on plurality rather than the majority, while others may require a run-off election. When this happens, the top two candidates are placed on a ballot again to ensure a majority will occur.

Ranked-choice voting may seem costly at first, but eliminates the need for a run-off if no candidate wins a majority of the first-place votes in the initial round. Instead, the candidate with the fewest first-place votes is eliminated and those ballots are adjusted so that the second-place candidate on each of those ballots is elevated to the first-place spot. The ballots are counted again to determine if the additional first-place votes result in a majority. If not, the process is repeated until a candidate has secured a majority of the votes.

Economists study voting behavior and analyze political systems in the field of public choice economics. We often talk about the decision of groups, but groups can’t make decisions. Individuals are responsible for their own decision, and those decisions are aggregated to determine the group outcome. Public choice economists study how diverse (and often conflicting) preferences of individuals are expressed when combined together to represent a single unit.

When it comes to analyzing voting behavior, economists often focus on a concept known as the median voter theory. If people’s preferences can be distributed across a range, say from 0 to 100, on how much they support a given candidate, the preferences of the “median voter” should determine the outcome of the election. Under this framework, candidates holding extreme preferences on one end of the spectrum should lose to candidates with more moderate platforms. Over time, candidates tend to converge to the middle position if their focus is on winning elections rather than staunchly defending their beliefs. This theorem should still hold in a ranked-choice system, since extreme candidates still need to garner second and third-place votes in case the top candidate doesn’t earn a majority of the initial votes. Oddly enough, political parties have consistently become more polarized over time rather than converging to the center.

One of the goals of ranked-choice systems is to eliminate the need for a run-off election in order to determine a majority. A ranked-choice system automatically conducts the run-off using a voter’s preference rankings. Economists, however, aren’t completely sold on the ranked-choice voting system as being a better alternative. The IGM Forum asked influential US economists to compare a run-off system with a ranked-choice system with the following prompt:

Rather than using second-round runoffs to settle elections in which no candidate wins a first-round majority, it would be better to use ranked-choice voting (as in the state of Maine) in which voters are encouraged to rank all of the candidates.

Respondents were allowed to skip the question or to respond that they were unsure. Those who answered the question were also asked to weigh their confidence in their belief. In the survey of European economists, 34% of the panel didn’t respond and another 21% were uncertain. US economists were much more supportive of a ranked-choice voting system, but the survey was conducted in 2018:

Some respondents leave comments, which can provide some insight into their rationale. European respondents focused mostly on the confusion that voters may experience in a ranked-choice system since it is more work to rank preferences than to select one option. US economists occasionally acknowledged this issue but also recognized the efficiency gains from not having to conduct a second election.

Minimum Wage as a Price Floor

Two states and one major city voted in favor of raising their state-level minimum wages. Nebraska voters supported increasing their state’s minimum wage from $9 to $15 per hour while Nevada voters supported an increase to $12 per hour. In Washington D.C., voters supported increasing the minimum wage for tipped employees to the minimum wage for non-tipped employees. The federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, but state-level minimum wages vary dramatically: Depending on the state, some municipalities may require higher wage rates.

Minimum wage policies act as a form of price control in labor markets. A price floor is a minimum price that employers are allowed to pay their workers. Whether that wage is effective depends on whether the price floor is set above or below the market rate for that worker. For jobs that pay well above the prevailing minimum wage, the policy is ineffective. Minimum wage legislation only has an impact on jobs in which the market (or employers) pushes wages below the prevailing wage in which the government mandates higher pay.

This policy applies largely to the typical hourly pay an employee earns. There are some special categories, depending on the state, in which workers can earn less than the federal minimum wage. In many states, workers who earn a significant portion of their earnings through tips could be paid (by their employer) as little as $2.13 per hour while workers with disabilities can earn as low as $3.34 per hour. Washington D.C. voters decided to remove the tipped employee exemption for their city, which will result in employers paying the higher municipal wage while still allowing workers to receive tips.

If you hear people argue about minimum wage laws as “basic supply and demand,” they are arguing on the assumption that labor markets are competitive. Depending on the locality, some markets where the minimum wage may be effective may also be competitive. In a number of other instances, however, markets may be monopsonistic. These markets are characterized by firms that have more control over wages and can exert downward pressure on wages. Firms in competitive markets can’t do that.

Monopsonistic markets are much more common than many realize. In the summer of 2021, the Biden administration issued an executive order highlighting their concerns over a growing amount of monopsonistic behavior in markets. For some context, check out a post from Monday Morning Economist last year:

In monopsonistic markets, minimum wage legislation could theoretically increase employment. This runs counter to the narrative often taught in principles courses that focus on competitive markets. If firms are exerting downward pressure on wages that force them to go below a more competitive wage, setting minimum wages equal to the competitive wage should theoretically “level the playing field” and induce firms to select the more competitive outcome. This means higher wages and more employment!

The study that sparked the initial controversy was conducted by David Card and Alan Krueger. They looked at employment in the fast food industry in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The study focused on the impact of New Jersey increasing its minimum wage in 1992, while neighboring Pennsylvania remained at the federal level. The two surveyed fast food restaurants just before New Jersey increased its minimum and again 10 months after the increase. There was no statistically significant change in employment in those New Jersey franchises, but employment fell in the Pennsylvania franchises. Card and Krueger’s results were widely interpreted as showing an increase in employment as a result of the increase in the minimum wage there. Over the past 30 years, however, the topic has been widely debated.

David Card won a share of the 2021 Economics Nobel Prize for his work on testing economic theories using natural experiments like the New Jersey minimum wage change. He, along with Alan Krueger and others, led the “credibility revolution” in economics. Alan Krueger died by suicide in 2019 at the age of 58. He was a professor of economics at Princeton and served as economic adviser to former President Barack Obama.

Colorado’s Proposition FF to fund a universal school lunch program was approved by 56.33% of registered voters [Colorado Election Results]

For the 2021-2022 school year, the federal government reimbursed schools participating in the National School Lunch Program between $3.66 and $3.90 for free lunches and between $1.97 and $2.35 for free breakfasts [Federal Register]

Based on data from 2021, there were 1,091,000 million adults over the age of 16 who were paid hourly wages at or below the prevailing federal minimum wage [US Bureau of Labor Statistics]

Nebraska’s Initiative 433 to increase the state’s minimum wage was supported by 58.52% of registered voters [Nebraska Secretary of State]

Nevada Question 2 to increase the state’s minimum wage was supported by 55% of registered voters [The New York Times]

Washington D.C.’s Initiative 82 to eliminate the tipped minimum wage was supported by 73.91% of registered voters [District of Columbia Board of Elections]