Hawks, Doves, and ARC Raiders

Game theory can explain how one of America’s hottest video games is… chill?

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

The winter holidays are almost here, which means millions of Americans will soon be catching up on sleep, travel, and whatever video game they’ve been hearing their friends talk about for the past few weeks. This year, one title has quietly taken over Steam’s “most played” list: ARC Raiders. It’s a sci-fi shooter set on a ruined Earth, full of scavenging, hostile robots, and players dodging danger to escape with as much loot as they can carry.

Nothing unusual so far.

What is unusual is the second headline about this game. Players keep describing ARC Raiders as one of the chillest extraction shooters of the year.

A high-stakes, player-versus-player looter-shooter with a relaxed community? That’s not the standard formula for online gaming in 2025. Games built around competition and risk-taking usually produce exactly that: competitive, risk-taking behavior.

So what’s going on here?

Economics has an answer. But before we get there, we need to understand what kind of game we’re talking about. Ready, player one?

A Quick Primer on This Kind of Game

We know not everyone reading this is an avid gamer, so here’s a bit of context before we get into the economics. Even if you’ve never picked up a controller, the incentives behind these games are easy to understand once you see them.

ARC Raiders belongs to a genre known as an extraction shooter. Players load their characters with weapons, armor, and a few useful items before venturing onto a large map filled with hostile robots called ARC. Once inside, the goal is straightforward: gather valuable items, complete objectives, and make it to an exit without dying. If you die, you lose everything you brought and everything you found.

This genre blends two familiar types of games. On one side is player versus environment (PvE) play, where the main challenge is fighting computer-controlled enemies. The other side is player versus player (PvP) competition, where the biggest threat comes from other humans. The game’s designers mashed these together and call it PvPvE.

In practice, that means every decision carries multiple layers of risk. A quiet building might hide a valuable item…or someone waiting to ambush you. A distant explosion might be a robot attacking someone else…or a sign that it’s time to steer clear.

And that’s exactly why ARC Raiders’ player behavior is so surprising.

Why is This Game… Chill?

Extraction shooters are usually the domain of players with enough time, skill, and patience to master every mechanic and punish anyone who hasn’t. The genre isn’t known for being welcoming, especially to casual players. Long firefights are common, and they often leave both sides worse off. ARC Raiders has been breaking that pattern.

Across streams, forums, and gameplay clips, players report relatively peaceful encounters. Strangers walking past each other without firing a shot. Brief voice-chat exchanges that end with both players going their separate ways.

The potential for chaos is still there. Two players can easily escalate into a drag-out brawl that ends with both losing everything they carried in. That kind of mutual wipe is a familiar outcome in this genre.

And yet, most of the time, players seem to choose the calmer option. That’s where game theory comes in.

From Prisoner’s Dilemma to Hawks and Doves

Economists use game theory to study situations where outcomes depend not just on your own choices, but on what others decide to do as well. These models come with memorable names (e.g, Cake Cutting, Battle of the Sexes, the Prisoner’s Dilemma) and they show up everywhere from business strategy to pop culture.

If you’ve ever taken a principles of economics course, you’ve almost certainly learned about the Prisoner’s Dilemma, where defection dominates, and cooperation is fragile. But that game isn’t the right one for what’s happening in ARC Raiders.

Extraction games look a lot more like the Hawk–Dove game, also known as Chicken. It’s a classic model of conflict where two players want the same prize but know that fighting over it could leave both worse off.

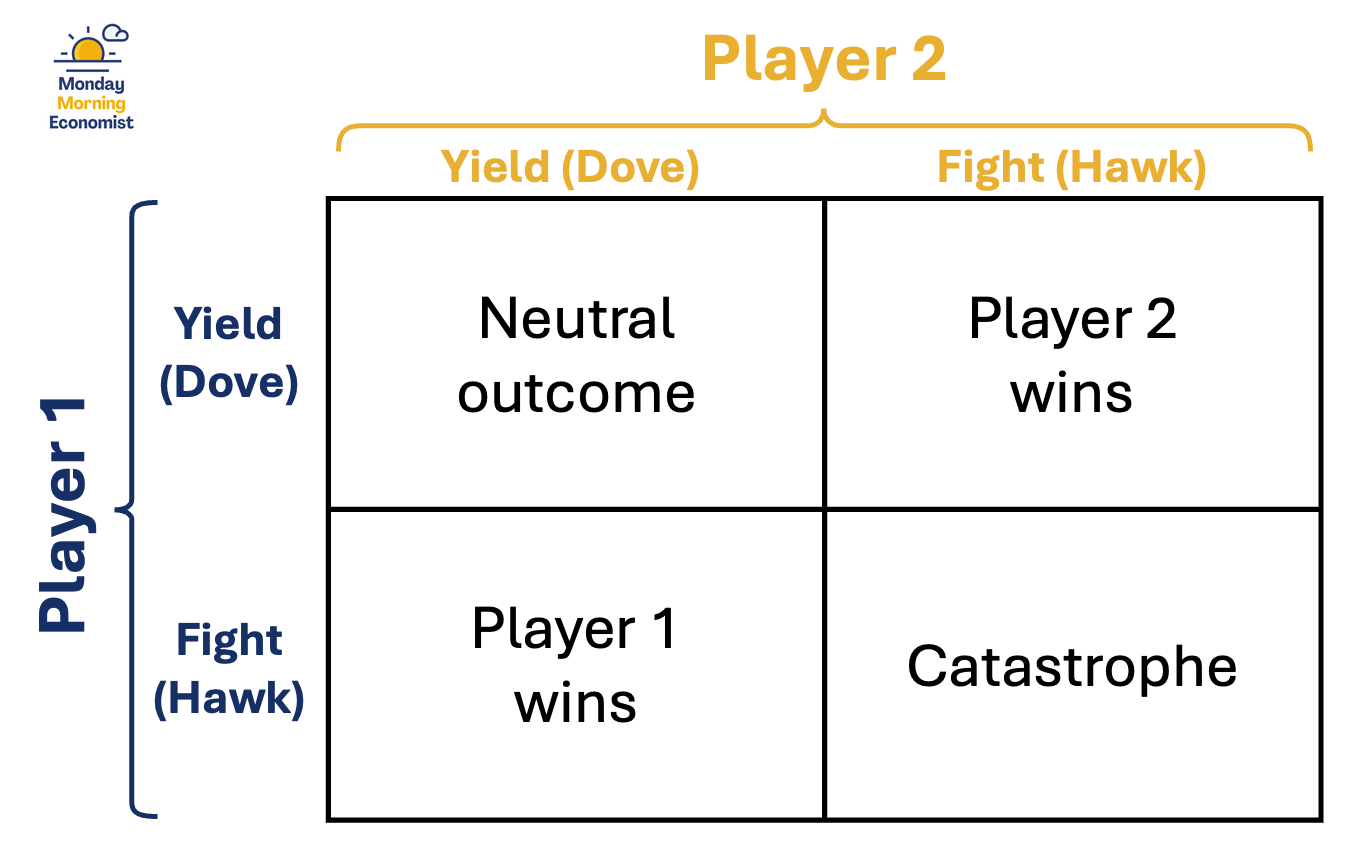

The structure is simple: hawks escalate and doves back down.

If two Hawks meet in a game, the conflict turns costly. If a Hawk meets a Dove, the Hawk wins. If two Doves meet, both walk away unharmed.

Economists usually represent these types of games with a payoff matrix, but the labels aren’t the important part. What matters is that the Hawk–Dove game produces multiple equilibria. Sometimes one player escalates while the other yields. Other times, the roles reverse. And in many real-world settings, players settle into a mixed strategy, choosing aggression only some of the time.

That mixed strategy predicts behavior that’s neither consistently peaceful nor consistently hostile. It’s just unpredictable enough to keep everyone cautious.

And that turns out to be a very good description of ARC Raiders.

Why So Many Doves?

The Hawk–Dove game often shows up in movies as two cars speeding straight toward each other. One driver swerves, the other doesn’t, and the story moves on. If both refuse to yield, they crash. If both swerve, no one really wins, but everyone survives. The most important thing to remember is that fighting is costly, and the worst outcome is mutual escalation.

When players load into a raid, they’re implicitly choosing how willing they are to escalate. Sometimes one player pushes for a fight, and the other backs down. Other times, both players slip past each other without exchanging a shot. And the costliest outcome? Two Hawks meet, and both players take so much damage that neither walks away with anything.

What makes ARC Raiders interesting is how often players avoid that last outcome. Dying wipes out everything you’ve collected. Prolonged gunfights attract robots and other players, turning small skirmishes into disasters. And because people enter with different goals, escalation is rarely the best response.

The result has been a gameplay where many encounters look like two Doves crossing paths: cautious, brief, and surprisingly polite. Players still mix their strategies, but the balance is weighted toward restraint. That has created a community that feels calmer than the genre’s reputation would suggest.

Final Thoughts

Payer behavior doesn’t emerge in a vacuum. It’s shaped by incentives, by risk, and by the environment designers build around each interaction. In this case, a genre known for aggression has produced a community that often chooses restraint.

But what is it about this particular extraction shooter that nudges players toward Dove-like behavior while other games in the same genre spiral toward constant conflict? Is it the cost of dying, the threat of third parties, or the way information is revealed and hidden? Or is something else happening entirely? Perhaps we're seeing a kind of sorting, where more aggressive players gravitate toward other games, leaving behind a community that’s more willing to yield?

Whether it’s the rules, the incentives, or the environment shaping behavior, the result is gameplay that feels refreshingly different from the usual online experience. To raiders of all types logging in to check out the Best Multiplayer Game of 2025, we’ll see you topside. And if you come across Noah in the game, he’ll be the one yelling, “Don’t shoot!”

If you know someone who’s planning to spend their break raiding, looting, or yelling at strangers on the internet, send this their way. It’s always more fun to play a game once you understand the economics underneath it.

Roughly half (49%) of global consumers characterize video games as fun, and 35% deem them relaxing [YouGov]

Over 190 million Americans play video games, and 78% of U.S. households have played at least one gaming device in the past 12 months [International Trade Administration]

The bestselling console of all time is the PlayStation 2, released in 2000, and sold 160 million consoles [IGN]

The vast majority of adults who play video games at least yearly report that they regularly play games alone (83%) [Gallup]

Friendly gaming isn’t the norm; 80% of all teens think harassment over video games is a problem for people their age [Pew Research Center]

This is awesome!

Cool piece. I saw an article saying that match making takes into account your style. Which then brings a separate question - can match making push to a different equilibrium and prevent people from gravitating to a different one.