America’s National Parks Just Got More Expensive For Some Visitors

A new fee structure for international tourists reveals the economic logic behind charging different people different prices.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Somewhere this week, a family will pull up to the entrance of Yosemite, Yellowstone, or the Grand Canyon. They’ll roll down the window, hear how much they owe, and then pause. In that moment, they’ll realize the price they’re being asked to pay is very different from the one they saw in guidebooks months ago when they first started planning the trip.

Starting January 1, international visitors are paying more to enter several major U.S. national parks. U.S. residents can still purchase an annual pass for $80, but visitors from abroad now face a $250 price tag. And those familiar “no fee” days? What was once open to everyone is now limited to U.S. residents.

This policy was announced months ago, but now it’s real. And for some visitors, it’s confusing. For others, it feels unfair. And for economists, it’s something else entirely.

What Economists Have to Say

In everyday language, discrimination usually means unfair treatment. In economics, the word has a much narrower definition. Price discrimination occurs when sellers charge different prices for identical goods based on consumers’ willingness to pay. The concept isn’t about intent or fairness. It’s about differences in demand.

From the National Park Service’s perspective, access to a park doesn’t cost more if visitors are from Paris, Texas, rather than Paris, France. What does differ is how sensitive those visitors are to the entry price.

International tourists have already paid for airfare, lodging, and transportation. Compared to those costs, a few hundred dollars at the park gate is unlikely to change their plans. Domestic visitors, on the other hand, are much more likely to adjust their behavior if prices rise, opting for a different destination or skipping the trip altogether.

Price Discrimination Happens All the Time

Once you know what to look for, price discrimination is everywhere. Airlines charge more to business travelers than vacationers. Movie theaters offer student and senior discounts for the same movie. Software companies sell identical products at different prices depending on who you are and how you use them.

Nationality-based pricing is also common around the world.

Many countries charge foreign tourists more to visit museums, historical sites, and national parks. These policies are often justified by congestion or wear and tear, but the pricing structure usually reflects something simpler: visitors who travel long distances tend to be less price-sensitive than locals.

And the U.S. already does this in other settings. Private companies like Disney World and Universal Studios offer discounts to Florida residents. State parks frequently charge less for in-state visitors. Hunting and fishing licenses follow the same pattern in many states.

National parks are just the latest place this logic shows up.

The Three Types of Price Discrimination

Economists typically break price discrimination into three broad categories, depending on how pricing is structured. The most extreme case is first-degree price discrimination, where each consumer is charged exactly what they are willing to pay. Think auctions or highly personalized algorithmic pricing. It’s difficult to achieve in practice, but it’s useful as a benchmark because it shows the upper limit of what a seller could charge with perfect information.

The next two forms are far more common. Second-degree price discrimination adjusts prices based on quantity or version rather than on who the buyer is. Bulk discounts and coupons are classic examples. If you buy more, the per-unit price usually falls. If you’re willing to take the time to clip coupons or sign up for a loyalty program, firms reward that effort with lower prices.

That brings us to third-degree price discrimination, which is what’s happening at national parks. Here, different groups pay different prices based on observable characteristics linked to willingness to pay. Once you start paying attention, you see it everywhere: student discounts, senior pricing, resident versus non-resident fees. And now, at least at some of America’s most famous parks, international visitors.

Final Thoughts

This is where price discrimination tends to get uncomfortable.

The economic logic is straightforward. Charging higher prices to less price-sensitive visitors can raise revenue while keeping access affordable for others. That efficiency story shows up everywhere, from airline tickets to subscription plans.

But national parks aren’t airlines. They’re public spaces. Many people see them as shared resources, not revenue-maximizing operations. So when prices change at the gate, especially in ways tied to identity rather than behavior, it can feel less like pricing strategy and more like exclusion.

What’s especially interesting is how much framing matters. People often push back hard against price discrimination when it looks like companies are charging them more, such as proposals for higher soda prices on hot days, dynamic fast-food pricing at lunch, or Uber’s surge pricing during popular events. Yet the same logic usually draws little attention when it’s framed as discounts for students, seniors, or residents.

Economics can explain how price discrimination improves efficiency. It can show how it raises revenue, expands access, and keeps prices lower for the most sensitive users. What economics can’t tell us is whether a particular price difference feels fair.

That’s the tradeoff at the heart of this policy. Understanding the economics helps explain why the new park fees exist. Deciding whether they feel right is a different question entirely.

Know someone planning a national parks trip this year? Or someone who loves a good discount? This one’s worth sharing.

Currently, 117 of the 417 national park sites collect entrance fees [National Parks Conservation Association]

Nonresident fees will be charged to each non-U.S. resident aged 16 and older who visits any of the 11 most visited national parks: Acadia, Bryce Canyon, Everglades, Glacier, Grand Canyon, Grand Teton, Rocky Mountain, Sequoia & Kings Canyon, Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Zion [National Park Service]

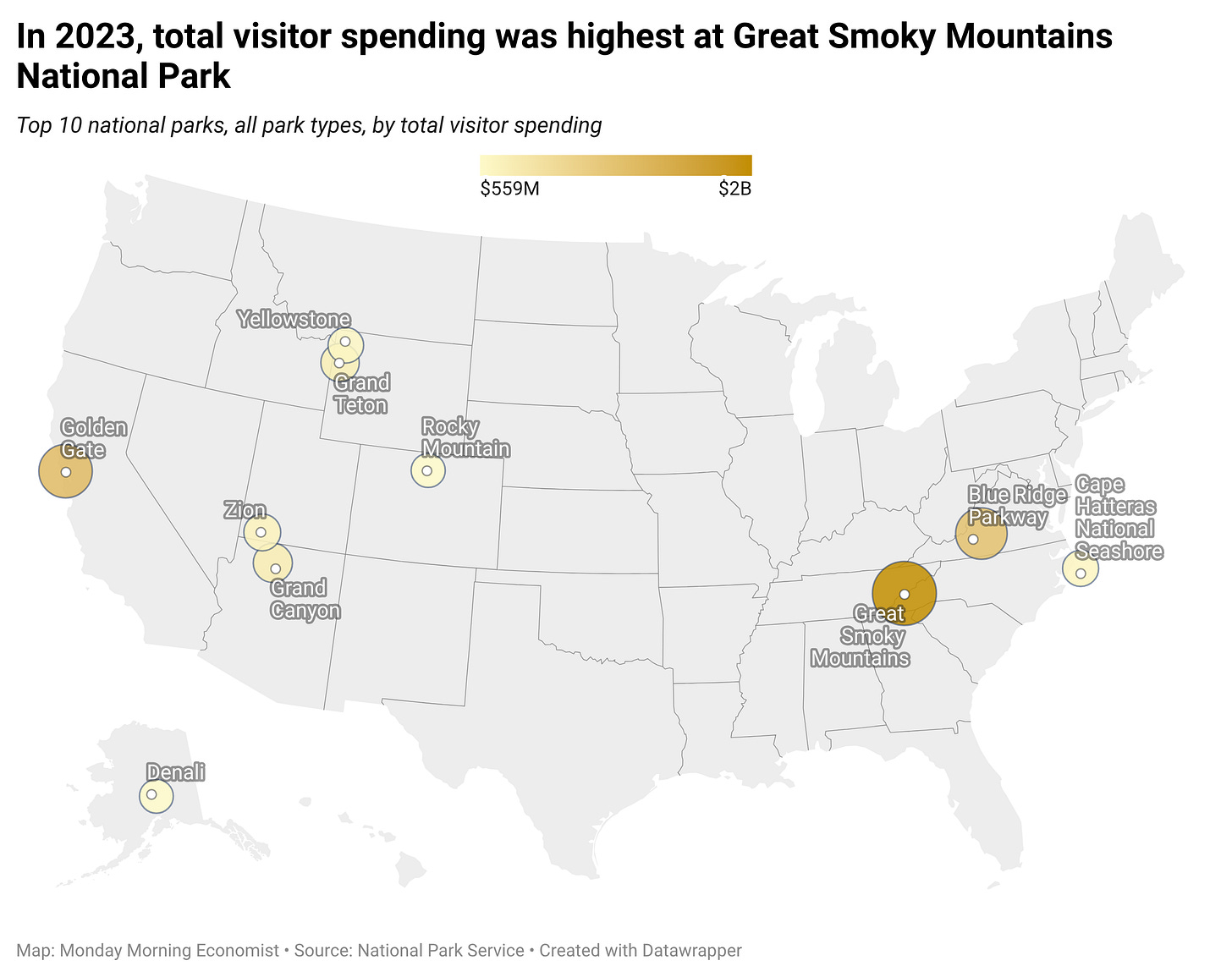

In 2023, there were 415,400 jobs in local economies tied to supporting National Park visitors, generating $19.4 billion in wages and salaries [USA Facts]

International visitors spent more than $147.3 billion on U.S. travel and tourism-related goods and services year to date in the first seven months of 2025 [International Trade Administration]

Survey data indicated that, on average, overseas visitors spent nearly $3,600 on their U.S. trip [National Retail Federation]

A subjective factor you are missing here is that the US is increasingly viewed as a place that is both dangerous and hostile to foreign visitors. Decisions like the park fees get lots of publicity in Australia (and, I assume, elsewhere), affecting the choices of potential visitors to the US who might never have visited a park even if they came.

Business idea for college students looking for summer cash: charge $100 to international tourists who would like to pay a lower price to enter the park by being the driver and showing their US drivers license at the gate. Then get dropped off someplace like the gift shop. Sit and watch a movie or read a book until the tourists are done and pick you back up to drop you off again.

It's Uber for national park visitors from foreign lands. Call it: Parker...