Our Thirst for Artificial Intelligence is Costly

Large language models like ChatGPT and Bard are energy-intensive and require massive server farms for training. Cooling those data centers also uses a lot of water.

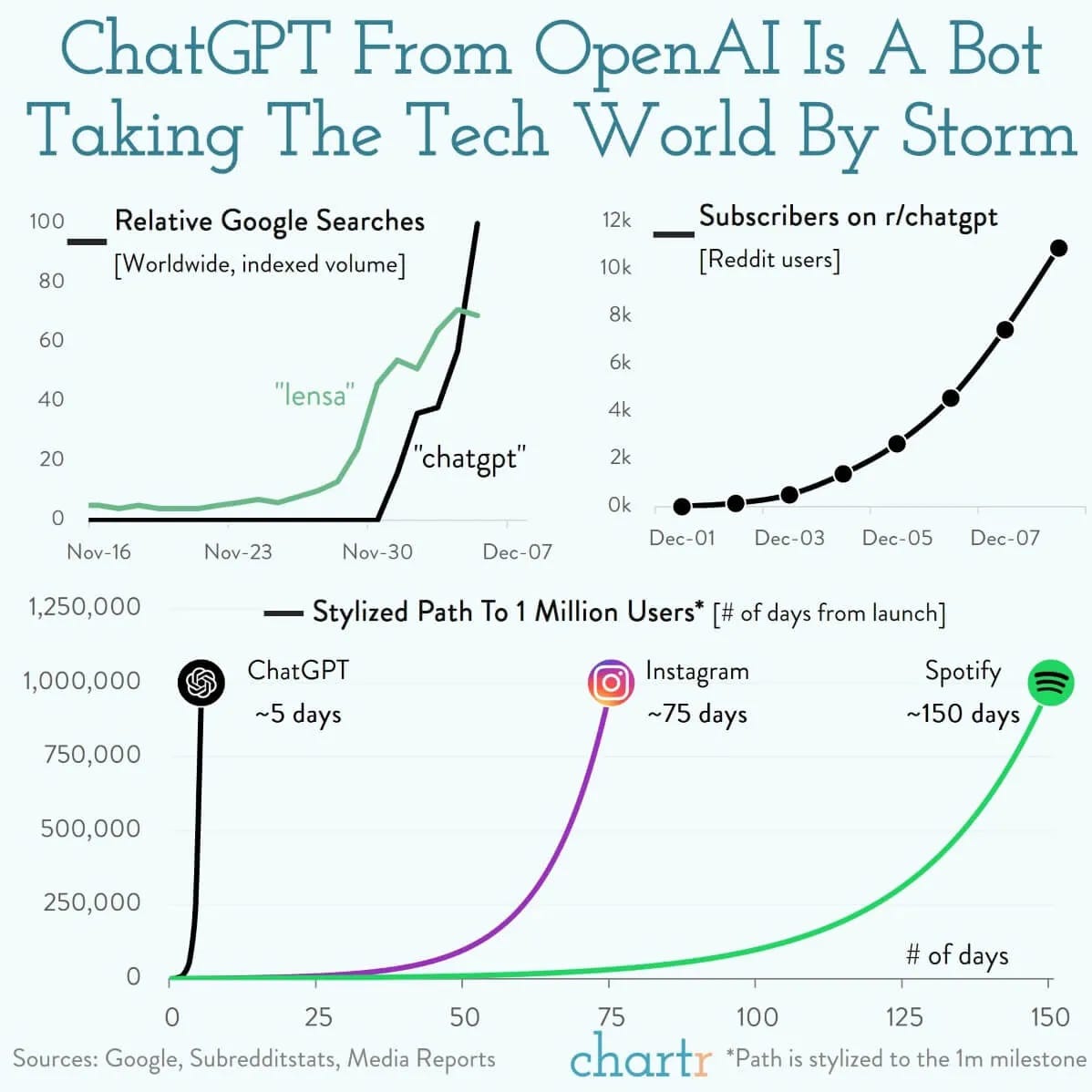

Researchers have studied artificial intelligence for more than 60 years. However, the past few months have seen a sudden surge in the development and use of AI-enhanced tools available to the general public. The explosion of AI-enhanced technology serves as a stark reminder that our future will likely be vastly different from what we know today, from the way we drive our cars to the way we communicate with each other.

As artificial intelligence continues to expand, we must remember some of the underlying economic concepts associated with its use. A commonly forgotten concept is that of externalities, which refers to the costs or benefits of an activity that are not borne by the parties engaged in the activity. A new study on OpenAI's water usage highlights the magnitude of externalities associated with artificial intelligence. The researchers estimated that OpenAI’s training of GPT-3 alone likely consumed more than 185,000 gallons (700,000 liters) of water. A user's conversational exchange with ChatGPT is equivalent to dumping a large bottle of fresh water on the ground.

This issue isn’t just limited to OpenAI and ChatGPT. Earlier this year, Google was criticized for using 1/3rd of a small county's water supply despite 98% of the region being in a state of extreme drought. Each of these stories highlights the social challenges caused by the tech industry, which relies heavily on data storage centers that require significant amounts of energy and water to operate. This issue will only become more pressing as different areas around the world experience severe droughts. Here’s a look at the U.S. drought monitor for the first few months of the year:

ChatGPT was released in November 2022, and quickly took the tech world by storm. More than a million users signed up within the first few days. Unfortunately, when we were using ChatGPT, we aren’t paying for all the water that OpenAI used to train the AI or to keep the data centers cooled down. While OpenAI may have paid for access to the water local water source, the environmental impact was unaccounted for in a price that users would pay when using the tool. While ChatGPT users enjoyed the benefits of an unpaid chatbot, the social cost was paid by others. ChatGPT users were generating negative externalities as they asked for new songs in the style of Taylor Swift and wondered how long their jobs would last in the future.

One way to better understand how negative externalities come to exist is to look at the difference between private costs and social costs. Private costs are those paid by the person engaged in the economic activity under scrutiny. For OpenAI, those private costs would include the cost of developing and running ChatGPT, operating the data centers, and maintaining the website. For users, it was just the time and energy to access the site since the early days of ChatGPT were available without a subscription fee.

The social cost of a particular activity, on the other hand, includes the private costs and any additional costs that are imposed on others in society. The additional cost associated with people posting their not-so-funny ChatGPT prompts to their favorite social media channels was likely fairly small. The social cost of creating ChatGPT, however, includes all of OpenAI’s private costs of physically setting the system up plus the additional costs associated with heavy water usage, which are higher if their servers are in areas going through severe drought conditions.

Extracting large amounts of water can lead to the depletion of local water resources, which can affect ecosystems and endanger the survival of certain species. While some portion of water is extracted and returned to the source, a portion of the water is consumed through evaporation. A large amount of energy is required to pump and treat large amounts of water, and that can also result in increased greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, leading to additional environmental and health costs.

Individuals often make decisions about how much economic activity to undertake based on their own private costs and benefits. Private costs, however, don’t fully reflect the social costs associated with their actions and therefore aren’t accounted for when deciding how often to use a site like ChatGPT. Since ChatGPT appeared relatively cheap to individual users, people allocated too many resources toward that activity. Continued overconsumption can have negative consequences for the environment and other parties affected by droughts. So, what can be done to address these externalities as the number of data centers in the U.S. continues to grow?

These looming social concerns highlight the need for policies and regulations that would account for the social costs of increasingly more tech-influenced lifestyles. The end goal of such policies should not be to halt technological growth, but rather to ensure that the social costs of such growth are appropriately reflected in economic decision-making.

One possible solution for addressing negative externalities is to implement a tax on the activity that is based on the size of the additional cost imposed on society. This tax would increase the cost of using ChatGPT in proportion to the amount of water or energy OpenAI uses. By internalizing the external costs, this tax would ensure that the full social cost of using ChatGPT is reflected in its price. This would incentivize users to use the tool more efficiently or it might incentivize companies like OpenAI and Microsoft to develop more sustainable practices.

For those who want to dig a bit deeper, these types of taxes are known as Pigouvian taxes and are based on the work of economist Arthur Pigou. He argued that when externalities exist, the market fails to allocate resources efficiently. By internalizing the external costs, a Pigouvian tax can help correct this market failure and promote more efficient resource allocation. Economists are largely supportive of such policies to address environmental issues.

As society continues its march toward a more technologically-enhanced future, we must ask ourselves whether it’s worth the environmental costs associated with extracting such large amounts of water to power these systems. Water usage isn't just an environmental issue but also a matter of resource allocation. As water resources are under increasing pressure, it's essential to consider how to use this precious resource. Technological advancements come with significant benefits, but we need to carefully evaluate them against the potential costs to society.

ChatGPT would need to “drink” a 16.9 oz water bottle in order to complete a basic exchange with a user consisting of roughly 25-50 questions [Gizmodo]

About 20% of data centers in the U.S. rely on watersheds that are under moderate to high stress from drought and other factors [Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory]

By 2071, nearly half of the 204 freshwater basins in the U.S. may not be able to meet the monthly water demand [Earth’s Future]

Data centers are big energy consumers—a hyperscaler’s data center can use as much power as 80,000 households [McKinsey & Company]

Data centers accounted for around 1% of global electricity demand in 2020 [Science]