Statistical Discrimination in College Admissions

Universities can still achieve their diversity goals, but it won’t be as easy as before.

A recent Supreme Court ruling has ignited a fiery debate about equal opportunity, meritocracy, and the unintended consequences of well-intentioned policies. The ruling primarily focused on the constitutionality of considering race systematically in college admissions, but it also sheds light on the broader issue of statistical discrimination and its impact on marginalized communities.

At the core of statistical discrimination lies the human tendency to make decisions based on observable characteristics and group-level stereotypes rather than individual merits. This type of discrimination occurs when individuals are treated differently due to the statistical association between certain characteristics and perceived outcomes. Biases, unconscious or otherwise, can influence decision-making processes and lead to disparities in opportunities.

Statistical discrimination should not be confused with prejudice, although they both involve making judgments based on group characteristics. Prejudice refers to preconceived attitudes about individuals or groups based on irrational beliefs or biases. It involves a subjective and often negative perception of others. On the other hand, statistical discrimination is based on observable patterns and statistical associations between certain characteristics and outcomes. It is a rational response to incomplete information, but it can still perpetuate biases and lead to unfair treatment.

In the recent Supreme Court ruling, the majority of justices expressed concerns about the emphasis on a single metric, namely race, in college admissions decisions. They argued that different racial and ethnic groups at Harvard and the University of North Carolina were being judged based on group-level attributes rather than their own individual association with those attributes. In essence, the Supreme Court outlawed statistical discrimination in the college admission process.

The Harvard and U.N.C. admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping and lack meaningful end points. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today.

Chief Justice John Roberts

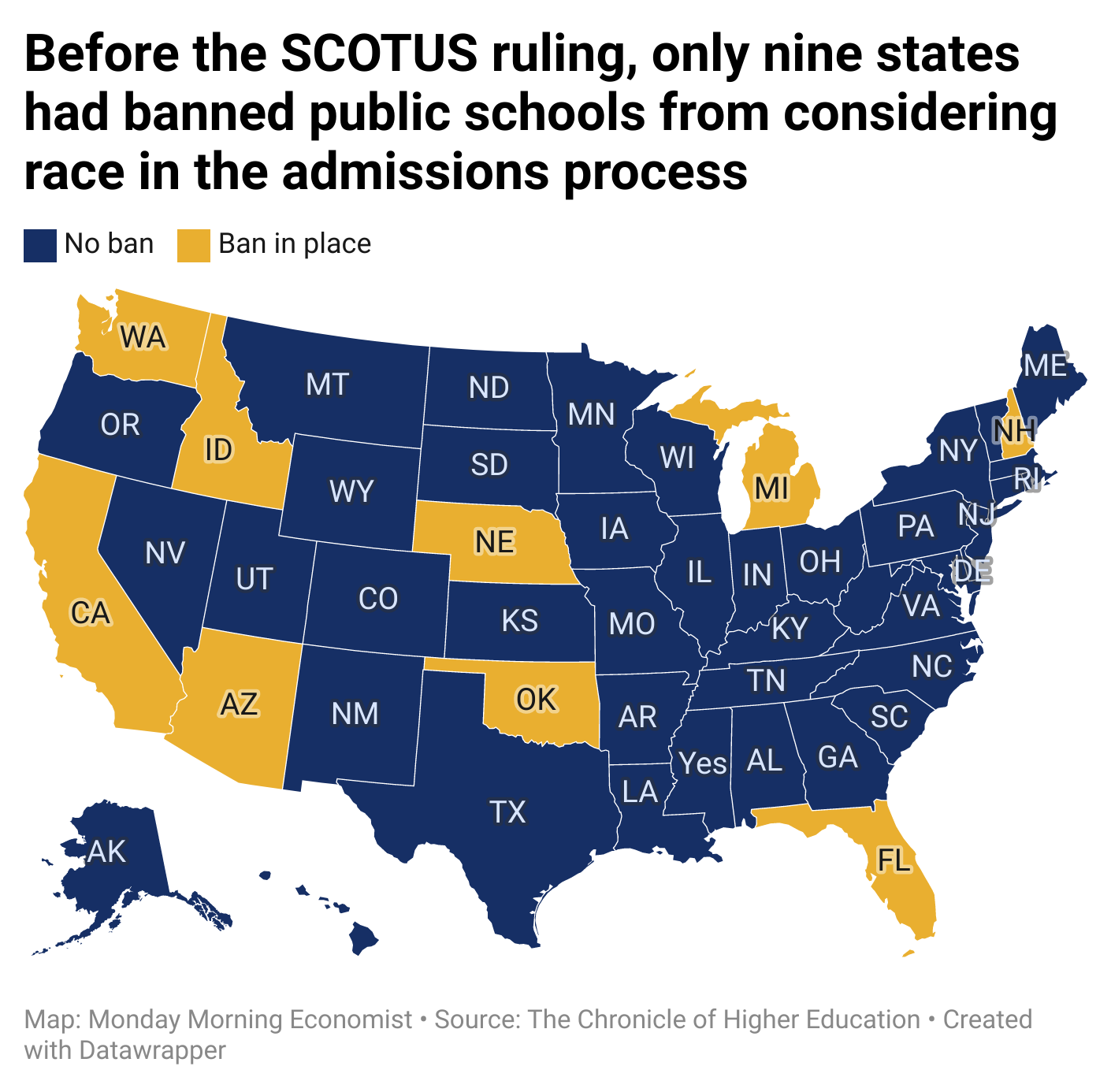

While the court cases were focused on admissions practices at two universities in the United States, the new ruling will apply to all academic institutions that accept federal funding. The only exceptions to the ruling, for now at least, were at military academies. The justices believe that ‘potentially distinct’ military interests allow for the academies to continue using race-conscious admissions in identifying future officers. Prior to the ruling, affirmative action programs were banned in only nine states:

Now that admissions officers are prohibited from considering race as a broad category, they must rely on other characteristics to assess an applicant's background, capabilities, or potential contributions to campus diversity. Admissions officers will likely focus more heavily on supplemental essays for evidence of how race has influenced a student's lived experiences. Chief Justice John Roberts, in his majority opinion, emphasized that universities can still consider an applicant's discussion of how race affected their life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or other factors:

…[N]othing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.

This more individualized approach to considering race in admissions moves admissions officers away from group-level attributes and toward the individual characteristics of each applicant. Admissions programs are still allowed to rely on other observable traits, such as extracurricular activities, zip codes, or family backgrounds, which may be correlated with an applicant's race or ethnicity.

A more personalized approach to the admission process, rather than treating all applicants from a single group as the same, is a common theme among the Supreme Court majority opinion and even critics of the ruling. While President Biden says that he “strongly disagrees” with the ruling, many of his statements align with the Chief Justice’s remarks that students should be given preferential admission based on their racial/ethnic background, so long as it’s tied to their individual personalities:

Statistical discrimination extends beyond college admissions and permeates various aspects of our lives. In some instances, statistical discrimination is legal, such as when insurance companies charge young male drivers higher rates based on statistical risk factors. In other cases, it is illegal, as it discriminates against protected classes. For example, landlords may make racial or ethnic assumptions about a person’s name to assess an applicant's reliability or trustworthiness in housing markets. Even in healthcare, racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of certain conditions have been linked to implicit biases among medical professionals.

To further illustrate the unintended consequences of statistical discrimination, we can draw a parallel to the "Ban the Box" movement. This movement emerged in the 1990s and gained attention during the Great Recession. Its goal was to remove questions about criminal history from initial job applications, promoting fair hiring practices and giving individuals with criminal records a seemingly better chance at securing employment. However, an unintended consequence arose as some employers, unable to directly assess criminal histories, started making assumptions based on race. This resulted in a new example of statistical discrimination, disproportionately affecting black job candidates who were more likely to be assumed to have a criminal record.

Just as admissions officers at Harvard or UNC may have inadvertently assumed characteristics based on an applicant's race, employers too have been known to make judgments about an applicant's criminal record based on their race. While not all universities approach affirmative action in the same manner, the majority of justices believe that including race as a factor could lead some admissions officers to perpetuate biases and lead to unfair treatment.

Regardless of whether it’s in the hiring process or the admissions office, statistical discrimination is done in an effort to reduce the costs of making decisions. Some economists and economic pundits have already weighed in on the potential implications (or lack thereof) for minority applicants, but the most likely outcome of this ruling is that admissions offices will need to invest more time in reviewing applications and will need to increase their costs if they wish to achieve a diverse student body.

Combating statistical discrimination requires a comprehensive approach that tackles biases, challenges stereotypes, and promotes equal opportunity. Whether it's employment opportunities or college admissions, a holistic review process that considers a wide range of factors can help mitigate the overreliance on a single observable characteristic. It’s what the University of California system believes helped them achieve their goals after the state outlawed affirmative action in 1996. The goal should be a more comprehensive assessment of an applicant's potential, taking into account their unique experiences and capabilities. Universities can still achieve their diversity goals, but it won’t be as easy as before.

However, addressing statistical discrimination is not solely the responsibility of institutions and policymakers. Each individual also plays a crucial role in challenging stereotypes, confronting their own biases, and fostering inclusivity in their communities. Many American adults view the college admission process as a meritocracy, where high school grades and test scores are seen as the sole factors that should matter. Nearly 75% of U.S. adults do not believe that race should be considered a factor in admission decisions:

Statistical discrimination is a complex problem with no single solution. It requires a comprehensive approach that involves both education and policy changes. It’s easy for universities and companies to say they care about a diverse population, but the real test will be whether they invest money to make it happen. Initiatives that promote diversity, inclusivity, and cultural competence only go so far in addressing the biases that fuel statistical discrimination because the people that need to hear the message aren’t often in the room.

It's crucial to involve marginalized communities in decision-making processes that directly affect them. By amplifying their voices and including their perspectives, policies can better address the unique challenges they face. Addressing statistical discrimination is a step toward creating a society where every individual has a genuine chance to thrive and succeed, regardless of their background or characteristics. It's a journey that requires collective effort and a commitment to building a fair and inclusive future.

There are nearly 4,000 colleges and universities in the U.S., but only slightly more than 200 have highly selective admission standards, where fewer than 50% of applicants are accepted [NPR]

For the Class of 2026, Harvard accepted 1,984 students out of the 61,221 applications they received [Harvard College]

Among a survey of college graduates, 70% of respondents agreed that for most of American history, Black Americans were denied access to elite universities [YouGov]

Colleges and universities received $1.068 trillion in revenue from federal and non-federal funding sources in 2018 [USA Facts]

We will see what happens to the plaintiffs case against Harvard for favoring legacies

Re Legacies & Donors: The irony of the Court’s decision is that they are perfectly fine with policies that statistically discriminate in favor of less qualified white applicants.