A 10% Credit Card Rate Sounds Great. Here’s the Catch.

What happens when the price of borrowing is set by law

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

The average credit card interest rate is currently around 19.62%, down from a record high of 20.79% set in August 2024. If you regularly carry a balance, a 10% interest rate probably sounds like a gift. Prices are up. Budgets are tight. For many households, credit card debt feels crushing right now.

So when President Trump urged Congress to pass a law capping credit card interest rates at 10%, it landed with a thud of approval. I’m not sure economists were in that camp. Versions of this idea have been floating around for years, with support from both the left and the right. It’s gained a lot of attention over the past few days, but the economics behind it, however, are anything but new.

This is a classic case of attacking a symptom rather than the underlying problem. But it is a solution that is likely to make things worse, not better. Before we get there, though, we need to talk about what interest rates actually are.

Interest rates are prices

In the simplest terms, interest rates are the price of borrowing money. When a bank lends funds, it gives up the ability to use that money elsewhere. At the same time, it takes on the risk that the loan will not be fully repaid.

Interest rates compensate lenders for both of these things: the opportunity cost of lending and the risk of default. That is why credit card rates vary so widely. From a bank’s perspective, a borrower with a long credit history and stable income looks very different from someone with a thin credit file or a record of missed payments. Higher interest rates are not a moral judgment. They are a price that reflects a higher perceived risk of not being paid back.

Seen through this lens, capping credit card interest rates at 10% is a textbook price ceiling. It sets a legal maximum price below what the market would otherwise charge for many borrowers.

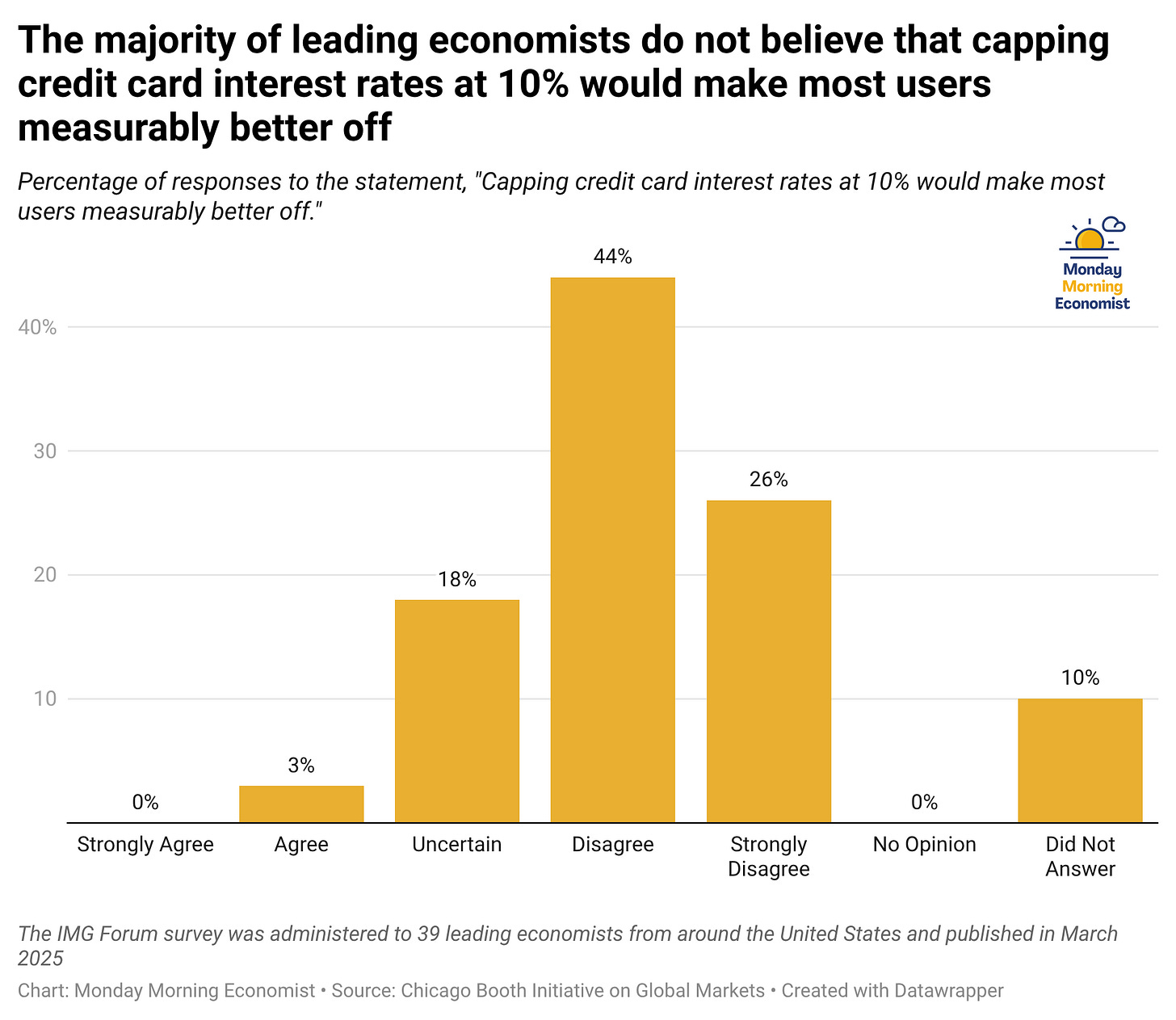

Economists tend to be skeptical of price controls because their side effects are highly predictable. That has been true across markets, whether we are talking about rent control or gasoline price caps. A cap on credit card interest rates would likely be no different. The consequences may not show up immediately, but they are well understood.

Side effect #1: Deadweight loss from too little credit

When the price of something is capped below its market level, less of it gets supplied. In this case, the “something” is access to credit.

With a 10% cap in place, many credit lines would simply stop making financial sense for lenders. The potential interest payments would no longer be enough to cover expected defaults or administrative costs. Banks would respond the only way they can: by lending less.

This is where deadweight loss shows up. Some borrowers would be willing to pay more than 10% to access credit. Some lenders would be willing to lend at those higher rates. In fact, they already do! But those mutually beneficial transactions would no longer occur under a binding rate cap.

The loss is easy to miss because it is invisible. There is no line item on a credit card statement that says “credit limit you were never offered.” But economically, it is a very real loss.

And here is the uncomfortable part. Most people who support a rate cap assume they will benefit from it. Very few expect to be the one whose credit line gets reduced or canceled in favor of someone with a stronger credit history.

Side effect #2: Inefficient allocation of credit

Interest rates do more than determine how much credit exists. They also help determine who gets it. When lenders are unable to price risk, they avoid it.

A binding rate cap pushes banks toward the safest possible customers: borrowers with higher incomes, long credit histories, and low probabilities of default. Ironically, these are the people least likely to be struggling under high interest payments in the first place.

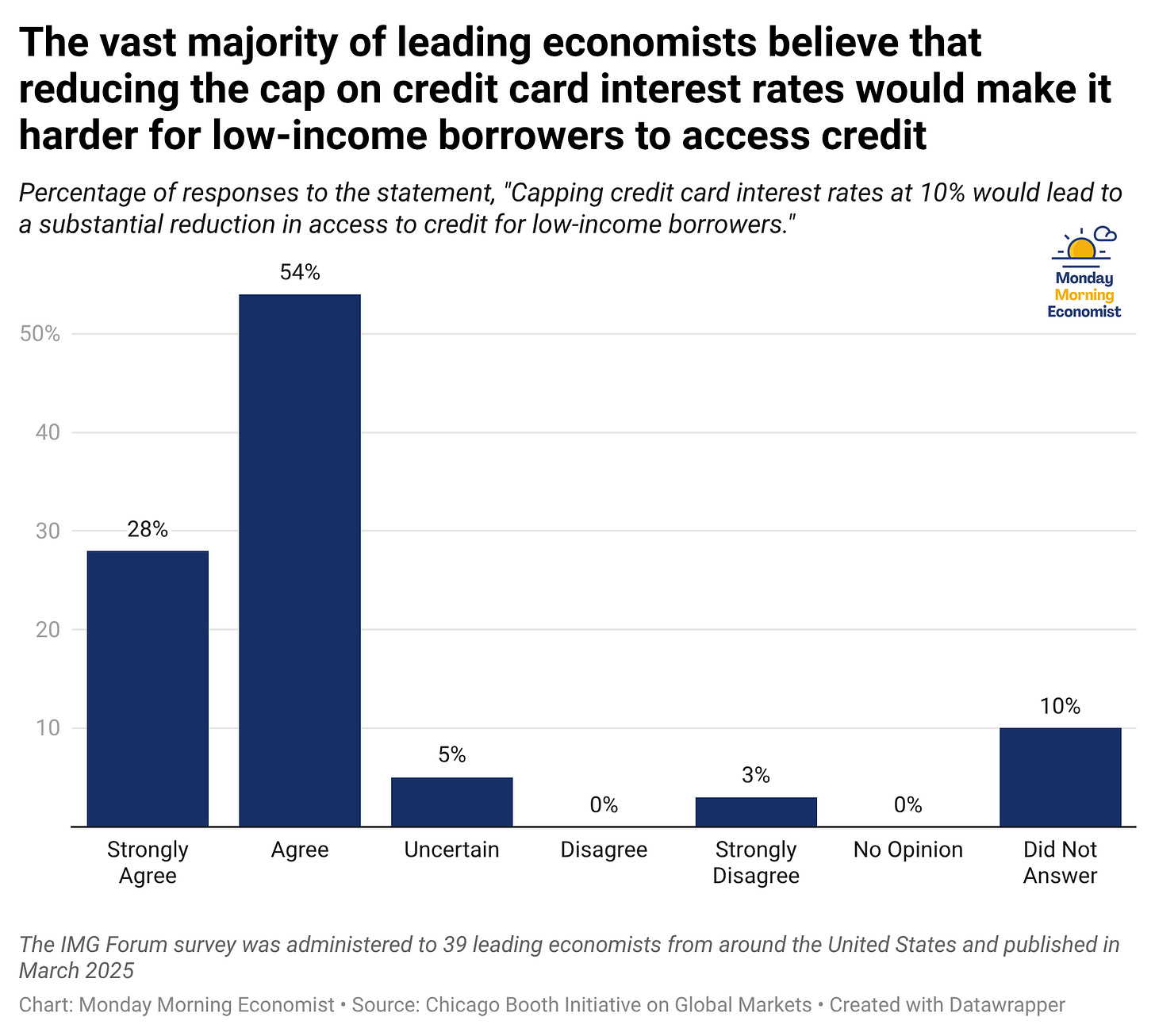

The borrowers most likely to benefit from lower rates, those with lower incomes or imperfect credit, are also the ones most likely to lose access to credit under a cap. Research on past interest rate ceilings has already shown this pattern. Credit access falls the most for higher-risk and lower-income borrowers.

This is not because banks are spiteful or indifferent to financial hardship. Lenders have a responsibility to remain solvent, and risk does not disappear when you legislate a lower price. It simply gets rationed.

The rest of the predictable fallout

The consequences of price controls tend to arrive together and reinforce one another. Banks may reduce credit limits or close accounts entirely. Rewards programs shrink or disappear because they are funded by interest revenue. Customer service and product quality suffer as profit margins tighten and incentives to compete fade.

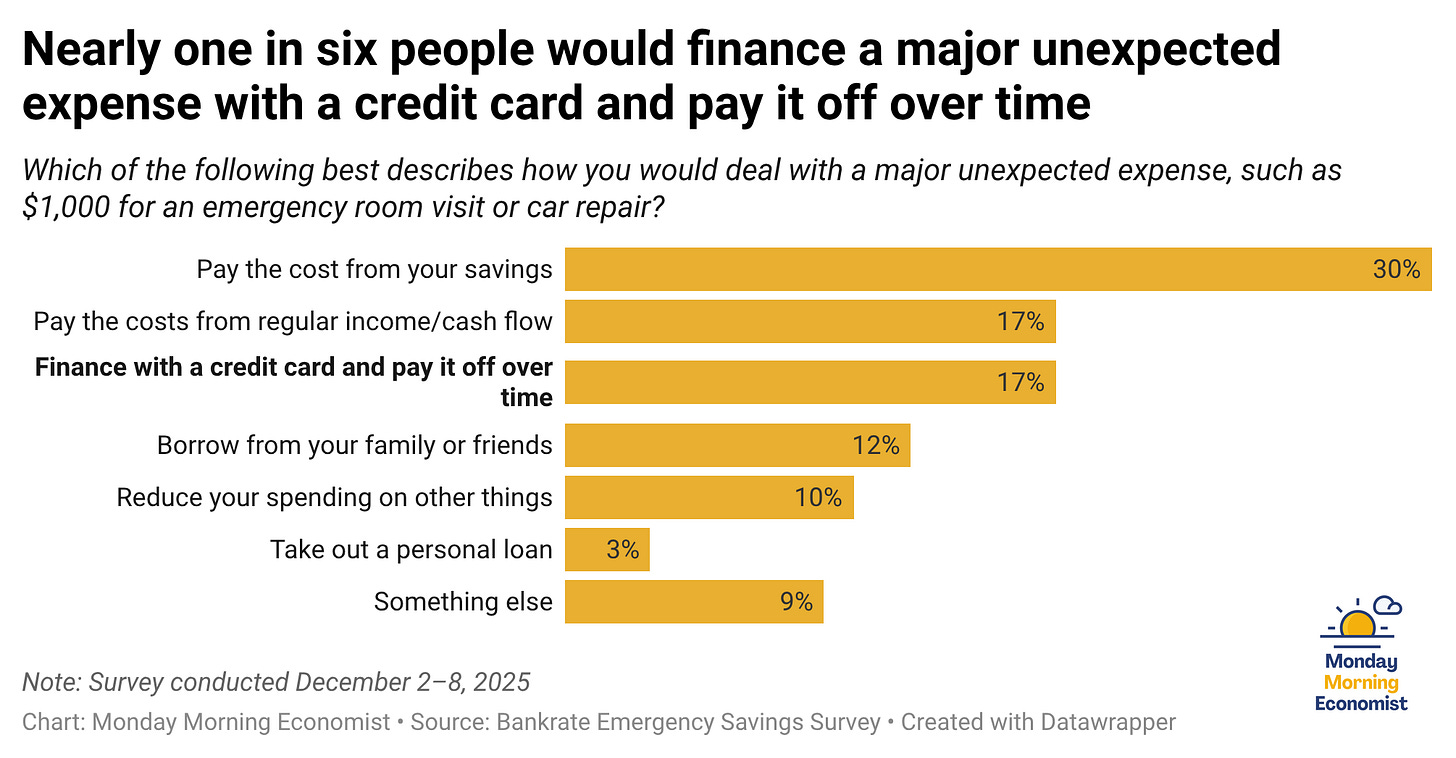

Borrowers who lose access to mainstream credit do not simply stop needing money. Instead, they will have to start searching elsewhere. Some apply for multiple cards, hoping something sticks, often damaging their credit scores in the process. Others turn to payday lenders, pawn shops, or informal loans from friends and family. These alternatives frequently come with higher costs, fewer protections, and worse long-term outcomes.

This is where the hardest economic truth lives. A credit card with a 20% or 25% interest rate that you can access may be better than a 10% card you cannot, especially in an emergency.

Final thoughts

The frustration underlying this proposal is real. Credit card debt is rising, and financial stress is becoming more widespread. But interest rates are not the root cause of the problem. They are a signal. If the goal is to improve financial health, solutions that work with market forces tend to perform better than those that try to override them.

Promoting financial literacy helps people understand how interest compounds and how to avoid carrying persistent balances. Clearer disclosure rules make it easier to compare cards and spot costly terms. Encouraging alternatives like credit-builder loans, secured cards, and employer-based lending programs can expand access to credit without blunt price caps.

Price controls feel compassionate because they focus on what people can easily see. The danger is that they quietly shrink what we cannot. The lesson here is not that affordability does not matter. It is that prices carry information, and ignoring that information rarely helps the people we most want to protect.

High interest rates feel unfair. That frustration is real. But good policy depends on understanding incentives and trade-offs. If this article helped add nuance to a heated topic, share it with someone who’s talking about credit card debt right now.

And if you think more people should have access to this kind of analysis, refer a friend to subscribe.

The average American household holds approximately $9,326 in credit card debt [Motley Fool]

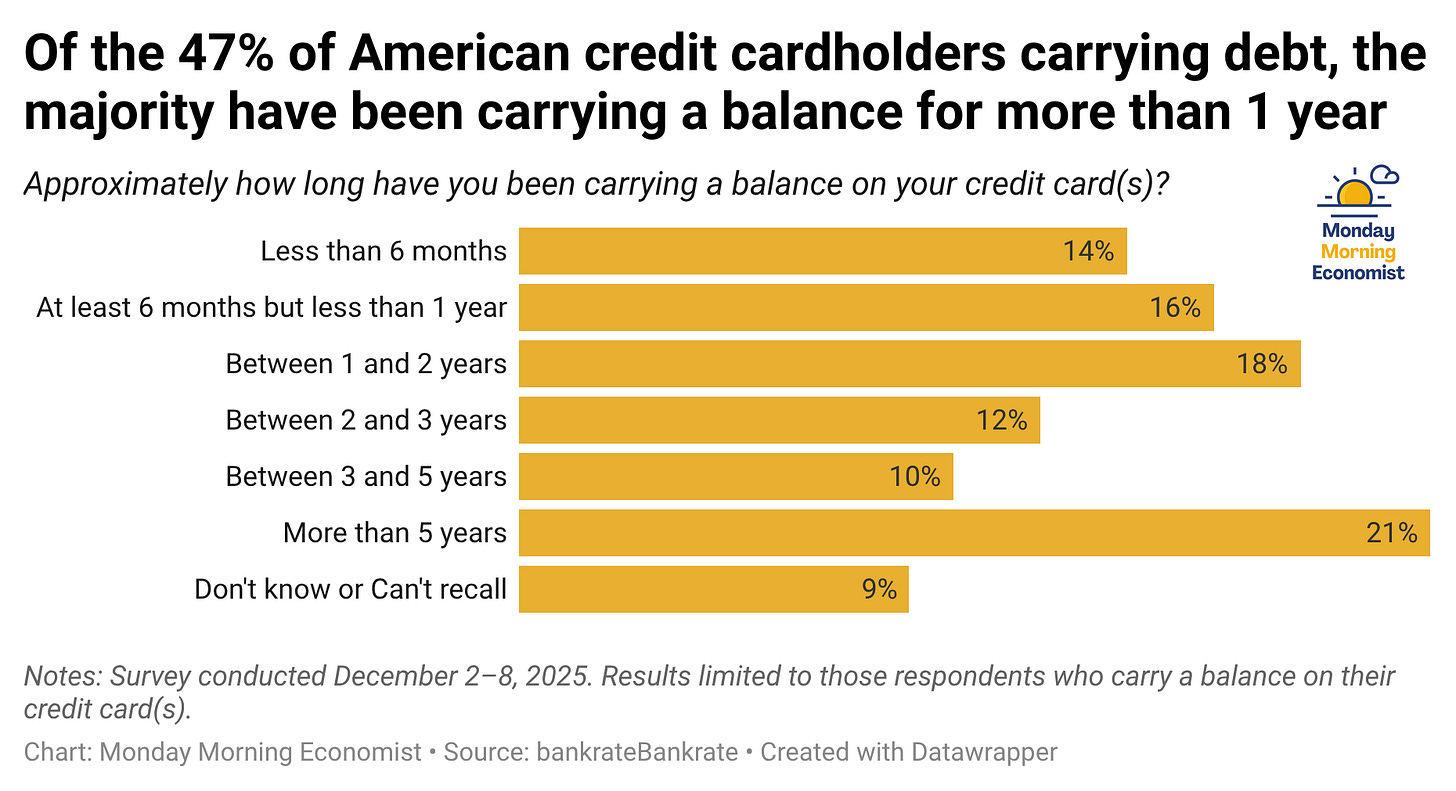

61% percent of Americans with card debt have been in debt for at least a year, up from 53% in late 2024 [Bankrate]

A 10% cap on credit cards could result in 74%–85% of open credit card accounts nationwide being closed or having their credit lines drastically reduced [American Bankers Association]

Credit card balances rose by $24 billion from the previous quarter and stood at $1.23 trillion [Federal Reserve Bank of New York]

82% of American adults are stressed about money [The American Heart Association]

Price controls often lead to black markets. Labor paid under the table to avoid minimum wages, or people converting their garage into an off-the-books apartment to avoid rent controls are common examples. Loans from family and friends sound like a nice alternative to credit cards. I think people are more likely to use payday lenders which also charge high interest rates for unsecured loans. Beyond that, credit markets for borrowers who need instant credit are likely to shift underground, exposing borrowers to usury. Of course, another possibility is that lenders develop an entirely new product that does the same thing as credit cards, but circumvents credit card regulation. In markets, as in Jurassic Park, life finds a way.

Why do they keep proposing plans that go against basic level economic principles? My AP kids spotted the effects of a price ceiling right away when they first heard about it. Same with all the tariffs.