The Shock of 9 Quid Ice Cream

Marnie and Mylah’s reaction to the £9 ice cream is a perfect example of how anchoring shapes our perceptions of price, value, and fairness

Have you seen the viral video featuring eight-year-old twins Marnie and Mylah from Burnley, England? The girls were at their local park with their mom, excited for a treat, when they discovered that the ice cream van was charging a shocking £9 for two ice creams. Marnie was particularly upset about the price and provided an economics-induced rant that many of us can relate to.

While it might seem like Marnie’s reaction was all about the high price, there’s a lot more going on here. This exchange gives us a perfect glimpse into the fundamental concept of “anchoring” in behavioral economics. It’s a principle that helps explain why we react the way we do to certain prices and other financial decisions. If you haven’t seen the video yet, take a minute to watch it first:

You can get the general idea of what’s happening, but if you’re not used to young British accents, I've provided a rough translation below:

Mom: Girls, what’s just happened?

Girl: So, there’s an ice cream van there. It’s silly, just 2 ice creams with 2 chewing gums in it, is bloody £9 for two of them.

Mom: 9 quid, for two?

Girl: Yea, 9 quid. That? He’s gonna get no where. The ones that come to my street have it £1 a piece or £2. That? He’s going to get no where with that.

Mom: No, he ain’t is he?

Girl: No! No, he aint!

Mom: That’s well bad, isn’t it?

Girl: Yea, he should know. And he only does bloody card. I stood there with me cash. Bloody hell!

Mom: That’s well bad, innit?

Girl: Bloody well bad. Yea, and I bet he can hear me.

What is Anchoring?

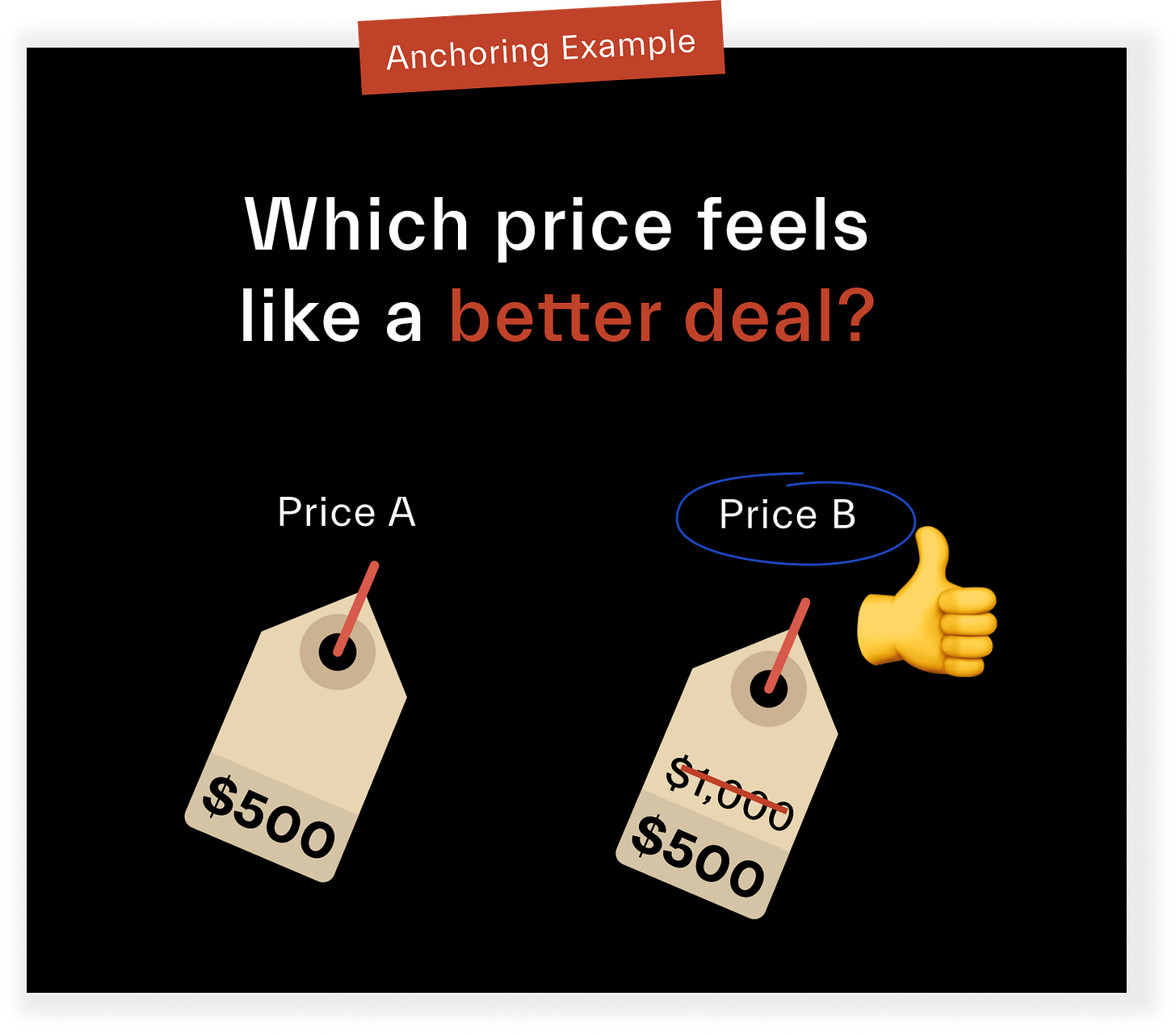

Anchoring is a psychological bias where we rely too much on the first piece of information we’re given (the “anchor”) when making decisions. Once this anchor is set in our minds, we form other judgments around it. As a result, there’s a tendency to interpret new information relative to the anchor in our minds.

Our two young girls’ anchor comes from past experiences with ice cream vans on their street at home. Marnie tells us that “the ones that come to my street have it £1 a piece or £2.” This price range set her expectations and became the anchor by which she judged future prices away from home.

As a result, £9 didn’t come across as just a high price, but it was shockingly out of line with their anchored expectations. Instead of assuming her neighborhood ice cream seller was too cheap, we get a strong reaction of shock and disbelief at the high price. Their blunt comment, “He’s gonna get nowhere with that,” highlights how expectations shape our perception of what is fair and reasonable.

Broader Implications of Anchoring

While our 40 seconds with these two young girls does a great job illustrating anchoring, this concept extends far beyond an ice cream van in Burnley. We encounter anchoring every day, whether we’re shopping online, discussing salaries, or deciding where to eat.

Take your favorite restaurant, for example. If the waiter introduces a chef’s special before you have had the chance to look at the menu, it may influence what price you consider fair for the items not featured. It’s in their best interest to offer up an expensive nightly special, so that you gauge the menu prices relative to that first piece of information. Suddenly, the rest of the menu seems cheap. Coincidentally, this strategy nudges customers towards pricier items that appear cheaper in comparison to the expensive special.

Retailers use anchoring, too. Stores often display the “original price” alongside the discounted price to anchor customers to the higher amount, making the discount seem like a significant bargain. A dress originally priced at £100 marked down to £50 seems like a great deal compared to if it were just priced at £50 all along. This tactic dramatically influences how we perceive value.

Have you considered buying or selling a home recently? The listing price often serves as an anchor. Even if a house is overpriced, potential buyers tend to negotiate down from the listed price, often paying more than they would if the home were priced more accurately from the start. Similarly, initial salary offers in job negotiations set an anchor. A higher initial offer can shape the entire negotiation, influencing the prospective employee’s expectations and the final agreement.

Final Thoughts

The incident at the park in Burnley isn’t just about kids discovering the harsh realities of inflation in the middle of England. Instead, it serves up a lesson in the everyday psychology of economics that affects us all.

Anchoring is a common behavioral concept that appears in marketing, negotiations, and many other areas of our daily lives. Marnie and Mylah’s reaction to the £9 ice cream is a perfect example of how anchoring shapes our perceptions of price, value, and fairness.

Monday Morning Economist is a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post with friends or becoming a paid supporter:

The average annual inflation rate is 2.5% in the United Kingdom and 2.9% in the United States [International Monetary Fund]

Belgians buy more than 16 kilos of ice cream per person—the most in Europe [Euronews]

In England, vanilla is the most popular ice cream flavor, followed by chocolate and then strawberry [The Independent]

There were 20,000 ice cream vans in the United Kingdom in the 1960s and 1970s, but that number has dropped to just 5,000 today [Lexham Insurance]

I'll buy (heh) that *maybe* there's some anchoring effect here, in the same way our parents (and probably now us) look at the prices of everyday things and recall how much less expensive they used to be, even when the current price is less than it would be if the price of yesteryear had matched inflation. But these girls are 8. They aren't old enough to have developed that kind of long memory.

I think their shock is better understood if we remember that money is simply a medium of exchange. If an ice cream treat is priced at 15 minutes of your labor equivalent, that's the case regardless of the value of a unit of fiat currency. But when it's suddenly being priced at 60 minutes of your labor equivalent, bloody hell that's outrageous.

Fascinating subject. I guess unlike the price of a pint of lager, or a cup of coffee, the decision to buy an ice cream from a van often only takes place a few times every summer. The consumer only has last summer holiday as a reference point.

The ONS ice-cream chart includes tubs of ice cream sold in supermarkets rather than those sold in vans. The latter has been impacted by the cost of fuel especially so I'd bet inflation is higher.